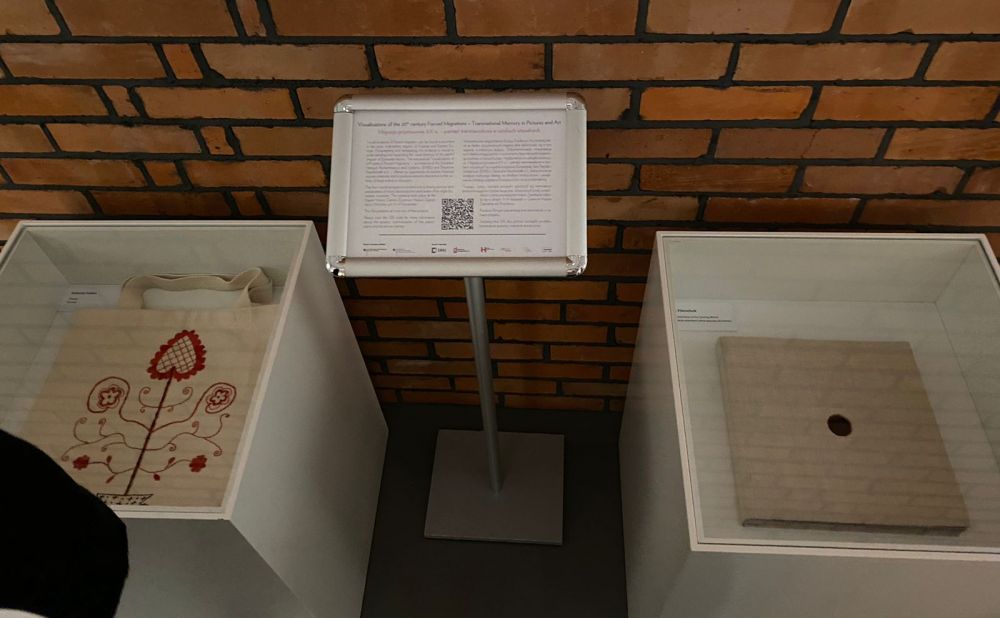

'Visualisations of 20th-century Forced Migrations' is a programme for young artists and professionals under the age of 35 interested in the complex histories of the European regions affected by forced migration. Areas of interest and expertise may include history, cultural studies, anthropology, sociology, journalism and the arts.

Applicants were asked to formulate an artistic or documentary project aimed at exploring and visually documenting traces of forced migration. This year the programme focused on the context of Second World War and the time period of 1933/49.

About Visualisations of 20th-century Forced Migrations

29 June – 19 November 2022, Berlin, Wrocław

The Authors About Their Works:

Liana Blicharska and Daria Koltsova

It Is Still Before My Eyes

The title of this project is inspired by an excerpt from Rukie Mamutovas testimony. Narrating about her family house in Qızıltaş, she talks about something common for all Crimean Tatars: “There was also a large and beautiful garden, it is still before my eyes, every bush and every tree.”

More than six million citizens of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics of various nationalities were resettled or deported. In August 1941, the government started the so-called “evacuation” from the Crimean Peninsula: Crimean Germans, Italians, Bulgarians, Greeks and Armenians were removed from their Homeland. Crimean Tatars - an indigenous nation originated in the 13th and 14th centuries - were all deported: in reports dated 20 May 1944 the following statements of different district committees (raikoms) could be found: “transported away”, “all transported away”, “all Tatars have been transported away”.

The project presented consists of two main parts: artwork and historical research. A stained-glass installation (materials: coloured glass, metal, wooden window frame) is accompanied by a study in the form of a Google Earth presentation.

The stained-glass works represent landscapes from Ay Serez, Yalta, Qiziltash, Yevpatoriia, Bakhchysarai, as well as Uskut and its surroundings. From the testimonies it becomes clear how important Crimean nature and soil are for the deportees. The stories and descriptions of Crimea are passed down from generation to generation. The images of the beloved land never seen by the children and grandchildren of the deported became dreams created by their imagination based on the memories and stories they were told from the time they were born. The installation represents images of Crimea in a wooden frame resembling the veranda windows of destroyed Crimean houses. Time erased all the details, but the combinations of colours and shapes were preserved forever, symbolizing something impossible to destroy or forget. The stained-glass technique symbolizes the ultimate fragility and vulnerability of a person's world in the face of totalitarian society.

The second part of this project is historical research about the deportation of Crimean Tatars, which was also a source for the stained-glass installation. The Google Earth presentation is based on two types of sources - oral testimonies and visuals. The former were collected in 2004-2011 as part of the Unutma project led by the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars in the Autonomic Republic of Crimea, Ukraine. These testimonies served as evidence for the Ukrainian government to declare the deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944 an act of genocide. During project duration, its Commission collected 950 testimonies. The archive containing them could be found online in the old version of the official website of the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars. The testimonies contain a lot of interesting information, often little or completely unknown, expanding to a large extent our knowledge about the methodology of the deportation from villages and cities of Crimea, the features of the transportation used, keeping Crimean Tatars in places of special settlements, the practically slavish use of the special settlers’ labour, as well as about the mass death from hunger, disease and unbearable living conditions.

The visuals used in our research are photos (the majority from private archives or international institutions such as The State Museum-Preserve Tauric Chersonese, Göteborgs Naturhistoriska Museum, State Catalogue of the Museum Collection of the Russian Federation, Russian State Library of Arts and from a private collection of Nizami Ibraimov). Two short documentaries presenting the Margilan silk factory and the Quvasoy cement plant in Uzbekistan (places where some of the deported persons worked) were recorded as a part of propaganda daily news in The Chronicle of Our Days made by Central Studio for Documentary Film in 1954 and 1959.

The idea of this presentation was to put excerpts of oral testimonies in a much more “natural setting” - the audience can more clearly see the interviewee’s environment - geography, topography, nature; The excerpts from testimonies are accompanied by photographs and videos, so the person who discovers the presentation could better understand what precisely the interviewee is talking about. The presentation is divided into two main parts - before and after the deportation. In the “Before” part, six places can be found: Ay Serez, Yalta, Qiziltash, Yevpatoriia, and Bakhchysarai. Each village, town, or city has a few pinned locations of houses of a particular interviewee (with an excerpt about the house, garden and family) and the most characteristic occupation/lifestyle for its inhabitants (life at the foot of a cliff, streets of old Tatar district, buildings related to cultural life, tradition and history). The “After” part consist of pinned locations of arrivals in Uzbekistan, followed by photos or videos of places where the deportees were assigned to work.

Daria Koltsova is a Ukrainian visual artist, curator and researcher born in Kharkhiv and based in Berlin since 2022. Liana Blicharska is a historian specialised in the 20th century. She collaborates with Territory of Terror Museum in Lviv.

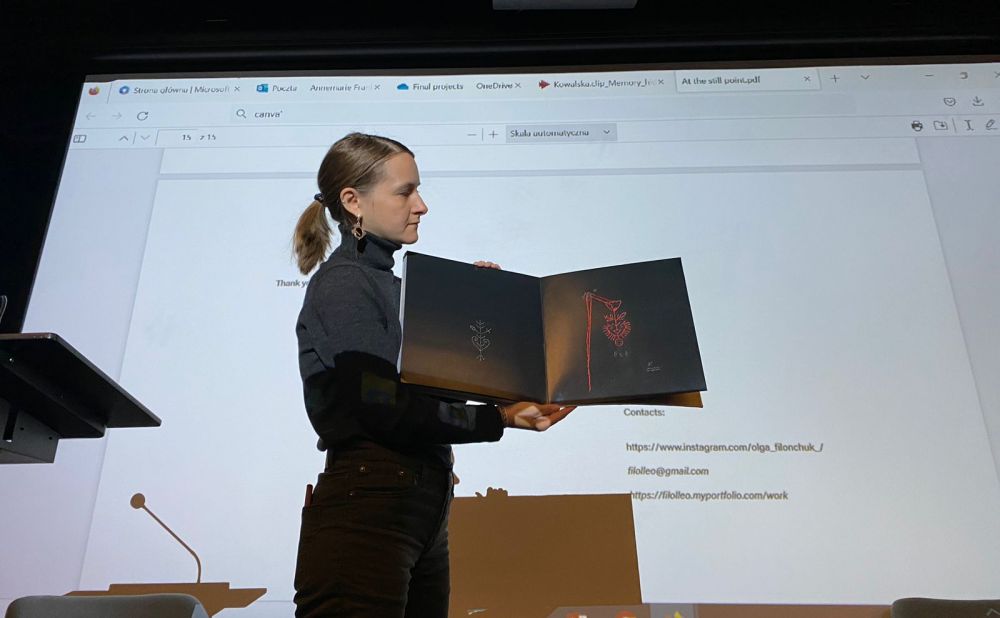

Olga Filonchuk

At the Still Point of the Turning World

This documentary art project is a photo diary that captures moments of the everyday life of the author, theater artist Olga Filonchuk, who was forced to leave Kyiv together with her sister and her seven-month-old niece in March 2022. Due to Russia’s war in Ukraine, the women have found refuge in the remote resort town of Bad Liebenstein, in the forests of Thuringia in Germany.

The photo diary is a collection of photos and texts that reflect the layering of feelings and memories of the author in her new reality; it is a meeting with other Ukrainian women who found themselves in a similar situation and in the same place. This is a pure attempt to record a moment of a flash, of shock, which from a mere second turned into weeks, then months, and stretched out in time. Now the author is in a safe place, in a calm point of the world’s rotation, in which she and the characters of her project are looking for their inner balance, peace and the possibility to inhale and exhale freely.

For three months, the author filmed the everyday life of herself, her family and other Ukrainian women forced outside the borders of their country. Using the stories of Ukrainian women and her own as an example, the author explores the existential questions facing all Ukrainian refugees who are at the crossroads of their lives abroad, while the war continues and their loved ones are staying behind in their Motherland.

In a safe place, in a calm point of the world’s rotation, can we find some peace of mind and the strength to move on, and is there a new point of reference? How are those invisible lines of force that connect you with the closest ones stretched like strings, and just now have become invisible and hypersensitive? Through symbolic visual details and the handmade nature of her photo diary, the author works with metaphors and self-identity.

Olga Filonchuk is a theatre set and costume designer specialised in puppet theatre. She was born in Kherson and she lived in Kiev before the war.

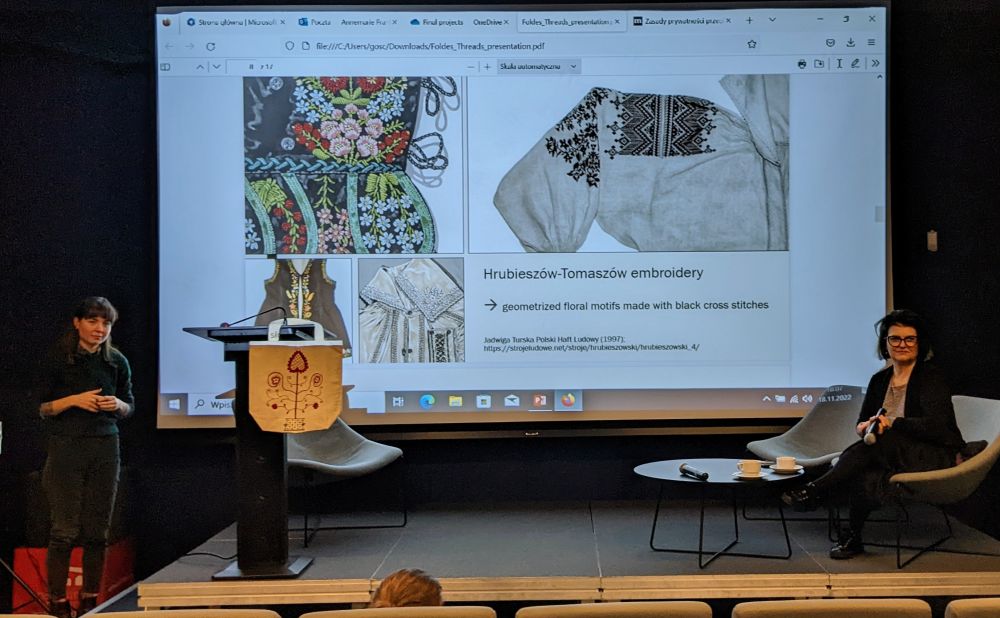

Antonia Foldes

Threads

Threads is an artistic project which aims to bring together different stories of forced migration through embroidery. Its design incorporates folk motifs and stitching methods from regions of past and present displacement in Ukraine.

After the Second World War, Poland’s borders were redrawn and the Polish population was forced to leave the eastern borderlands as part of a Soviet-mandated population transfer. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, millions of displaced persons are once again heading westward.

In line with Michael Rothberg’s theory on multidirectional memory, the project juxtaposes different histories without equating them. By refusing the zero-sum logic of competitive memory, the project instead encourages a dialogue between experiences to uncover new forms of solidarity. According to Rothberg, “Memory’s anachronistic quality – its bringing together of now and then, here and there – is actually the source of its powerful creativity, its ability to build new worlds out of the materials of older ones.”

Although ruptured by war, peoples’ stories do not end with their departure and so the embroidery project points to the role of women as keepers of traditions and carriers of our past. It takes a stance against the dismissal of private “home” practices and the feminine as inconsequential to wider public life. In defiance against the destruction of war, embroidery is a practice of creation and cultural transmission across generations and borders.

This theme of survival and victory of life over death continues in the design, which depicts a tree of life. The traditional folk symbol, which is common on ritual cloths in eastern Ukraine, also represents past, present and future. The tree incorporates geometric black cross stitches used in the former eastern borderlands of Poland, as well as bold red satin stitches found in eastern Ukraine. The design is embroidered onto a bag, an emblematic object of displacement which most persons will invariably use for their journey, carrying their past with them.

Born in London but raised in Germany, Antonia moved to Poland to research post-conflict memory across Eastern Europe. In the months following the Russian aggression she was a transport coordinator at one of Poland’s largest refugee reception centres, the Humanitarian Aid Centre in Przemyśl.

Joanna Kowalska

Memory Hidden in the Landscape –Traces of Forced Migrations in Pstrążna, Poland

Memory Hidden In the Landscape is a project for which the inhabitants of Pstrążna and I go on walks around the village. Forest and field paths, trees growing on former farms, and the remains of foundations surrounding home gardens mark our way and the stories told.

In this village, now located on the Polish-Czech border, in what is called the former Czech corner, many different migration trajectories intersected after the end of the Second World War. In Pstrążna, stories converge of families who came here in 1945 and later from the Borderland (Polish: Kresy) region or southern Poland with previous residents, who were forced to flee to the Czechoslovakian side because of the new state reality. Alongside these, there coexist stories of people who, while remaining in their hometowns, witnessed a sudden change in their neighbourhood, dictated by the end of the war and borders shifting.

I listened to these family stories during my walks with local residents — this method, in addition to the narrative, enabled us to map together places and paths of significance. While the recorded walks do not constitute a complete story, they allow for the visualisation of subjective family stories, as well as a fuller consideration of motivations, decisions, events and places relevant to my interviewees.

Starting the project, I hoped to gather diverse perspectives. During the first stage of the project, my guides were people currently living in or around the Polish side of Pstrążna. In the future, I hope to expand the stories to include the perspectives of former Pstrążna residents and their descendants living permanently in the Czech Republic and Germany, as well as other countries to which their families’ migration trajectories took them. In stories of forced migration, the not-so-obvious interweaving of political, economic and social threads which affect each family’s decisions and migration trajectories deserve to be heard separately.

Joanna Kowalska studies Anthropology at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and she works as field researcher in Poland and abroad.

Mladen Nikolić

The Lighthouses – Danube Swabians in Vojvodina

The Lighthouses is a visual exploration of the lives and fate of ethnic Germans from Yugoslavia in the form of a photo essay. Before the Second World War, about half a million Danube Swabians lived in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, most of them (around 330,000) in the multi-ethnic region of Vojvodina (today, an autonomous region of the Republic of Serbia). As a consequence of the war, only 28,869 remained there in 1948, while today, there are only about 5,000 Germans in Serbia.

This photo essay uses photographs from three different periods: before and during the Second World War, and contemporary photography of the lighthouses in Pančevo (Serbia). The first part (1930-1941) of the essay shows private family photographs before the war. The second one (1941-1944) combines family photographs with documentary photography of the war and migrations. The third shows contemporary photography (2022) of name carvings on the bricks of the lighthouses in Pančevo.

The structures were built in 1909, on the confluence of Tamiš and Danube rivers. At that time, Pančevo was going through industrialization and the lighthouses were built to allow safe passage of ships into the town. Since they were built, people found it amusing to spend time around the lighthouses and carve their names into the bricks of which they were made. On almost every brick, there is a name and sometimes the year when the carving was made. Today, these carvings show the multiculturality of the town throughout history. We can see Serbian, German and Hungarian names, as well as those of people of many other ethnicities that inhabited the town over the last century. However, while there were many German names carved into the bricks before the Second World War, there are almost none after the war ended.

This photo essay is an attempt to visualize the story behind these name carvings and the absence of German names after the Second World War through the usage of family and documentary photographs that show the lives of ordinary German people from Vojvodina in the period from 1930 to 1944.

Mladen Nicolić holds an MA degree in Social Studies from the University of Belgrade. He works as a data analyst and journalist specialised in photography and social topics.

Badri Okujava

Displaced Persons and the Buildings They Left Behind – Forgotten and Remembered German Remains in Georgia

Looking for a needle in a haystack - never was this metaphor more relevant than while work on this project continued.

The first task is to find the contemporary names of old streets. Once done with that, you have to make sure that the previous and current street numbers match, and finally, you have to have physical energy left in order to visit and photograph about five hundred houses in the city. Remember that they are not always located at the addresses indicated. Some have been demolished, some are falling apart, and some others have been replaced with completely new types of residential buildings.

81 years may not seem like a long time for history, but for visual anthropology it is eternity. Cities are changing at lightning speed and those changes are especially visible in post-Soviet cities, including Tbilisi.

The focus of the presented project is the Swabian German minority that lived in Tbilisi and neighbouring settlements from the mid-19th century until November 1941. The main part of the project is the topography of its deportation. Within the framework of topography, more than 400 residential objects were marked on the map of Tbilisi alongside with relevant pictures and the names of Germans living in them.

The main goal of the project was to delineate the topography of the deportation, which was achieved. A special website was prepared for the project presented, where a map of the topography of the deportation was placed, complete with relevant visual materials.

Badri Okujava holds a MA degree in Political Sciences from the Ilia State University in Tbilisi. He is a researcher at the Soviet Past Research Laboratory.

Andrea Škopková

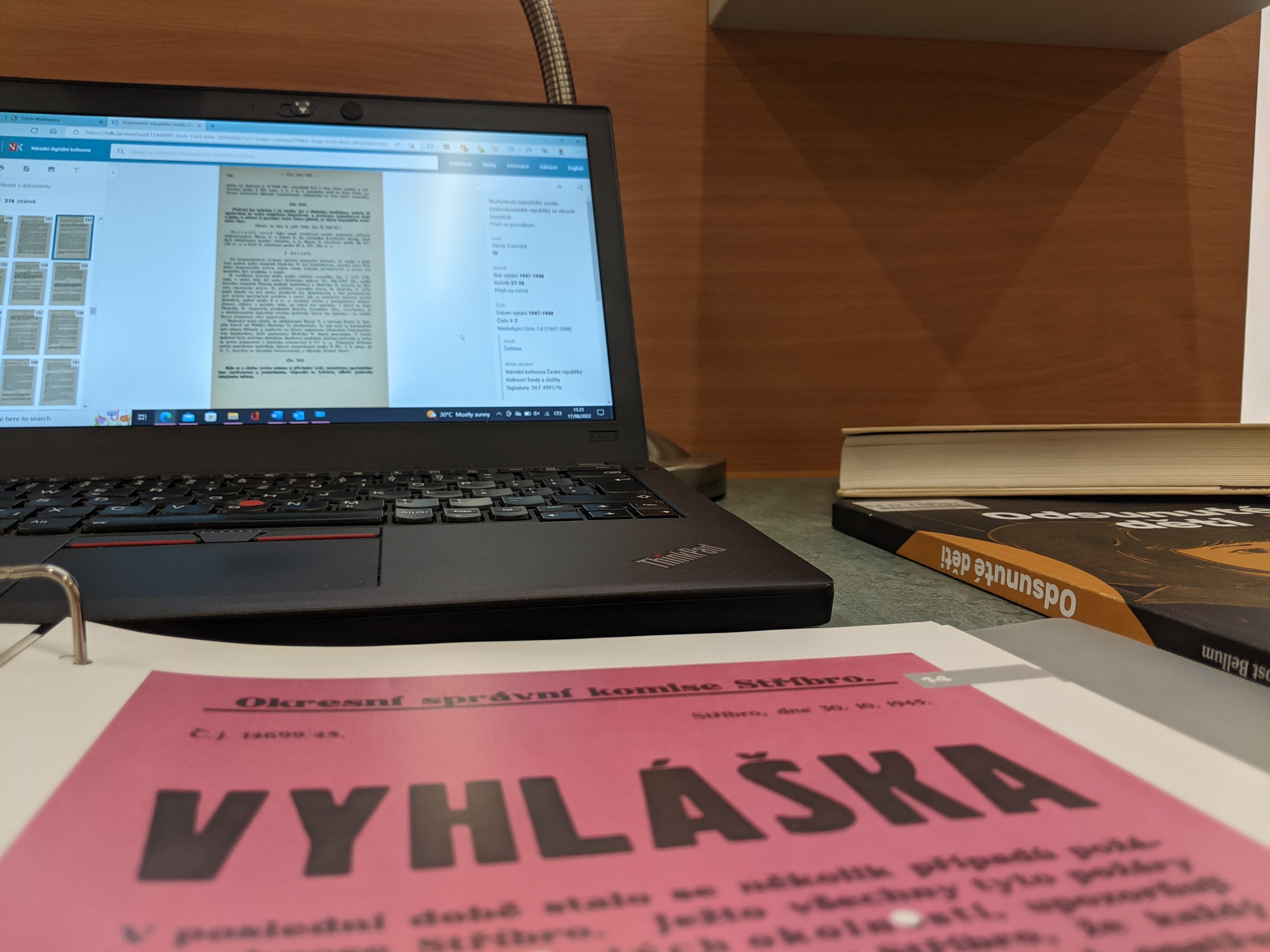

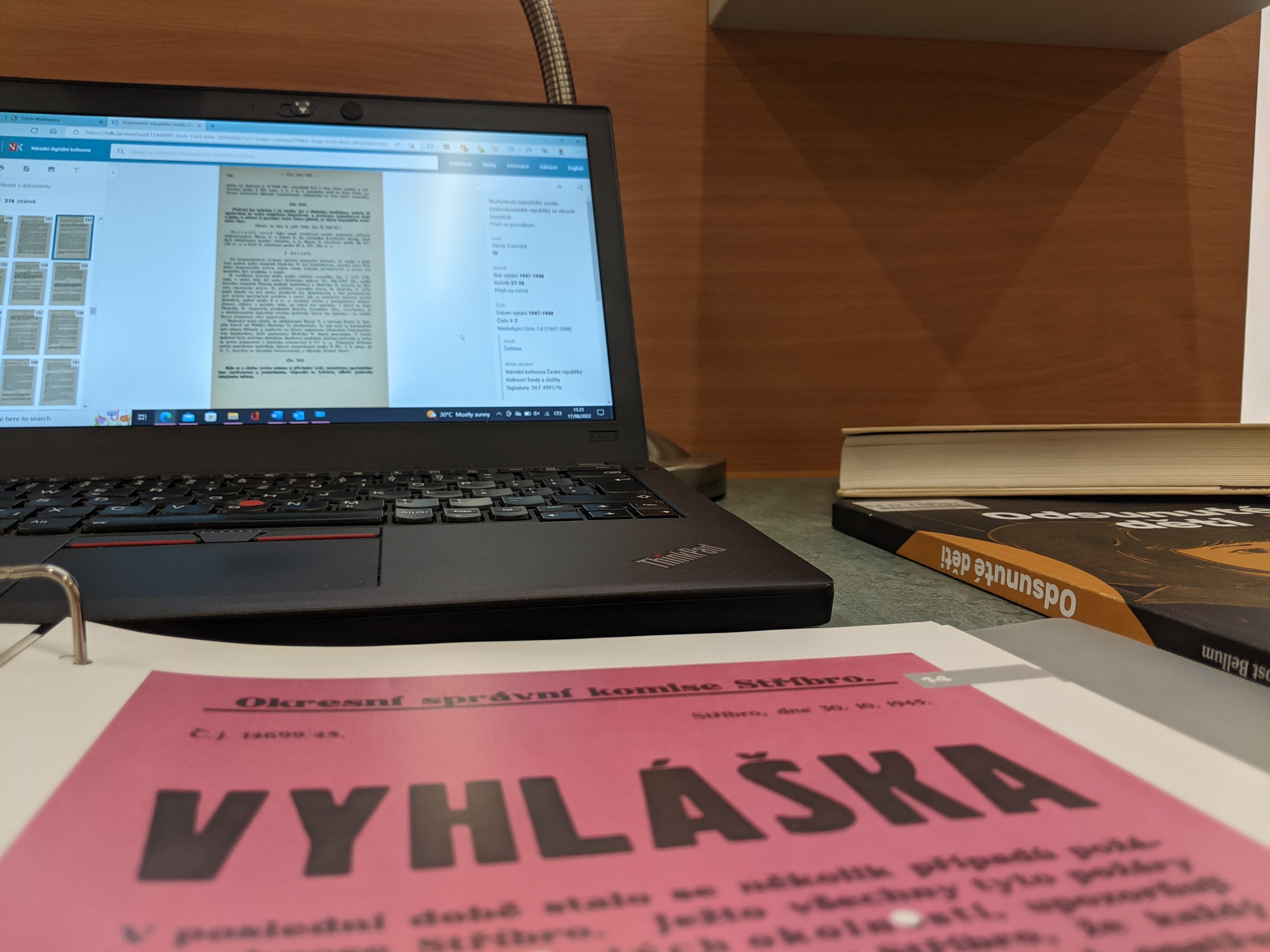

Images of Law and Injustice – Forced Migration in the Czech-German Border Area After 1938 and After 1945

The article deals with the question of the possibilities of visual and content analysis of historical photographs, using the specific example of photographs depicting the involuntary migration of the population of a Czechoslovak border region in 1938-1945.

In the first part, it deals with the historical and social context, involving available information combining both the objective and subjective reflection of all parties involved, as well as the viewpoints of various social science disciplines, especially law and sociology.

The second part focuses on the philosophical and theoretical foundations of image analysis and discusses the paradox of photography as a medium that embodies both facts (documentary photography, crime photography, etc.) and fiction (fashion photography, art photography, etc.). At the same time, it addresses the question to what extent images depicting forced migration can be considered documentary or rather illustrative – especially in the context of the fact that it is not always clear from the image itself exactly who the images depict, and at which moment in time.

The third part applies selected analytical approaches to examples of ”images“ documenting and illustrating the above-mentioned problematic period of Central-European history. Among the analysed images depicting the theme of the restriction of human and cultural rights, besides general images of persecutions, also included are images of commands and prohibitions as typographic visualisations of legal regulation. Last but not least, attention is also paid to the use of the theme of forced migration as a media (or even entertainment) narrative (photographs in the media, drawings in entertainment magazines).

Finally, as an outcome, the article summarizes the findings and outlines the possibilities for further research on the topic, which could find wider application in programmes focused on interactive interpretation of history and civic education.

Andrea Škopková is a law student and graduate in Journalism and Media Studies from the Charles University in Prague.

Kalina Trajanovska

Madžir Maalo: The ‘Refugees' Settlement’ in Skopje

Not many explorers – or locals – of the city of Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, are aware of the fact that one of the most central districts, known as Madžir Maalo, literally means a refugees’ settlement [from the Ottoman Turkish muhacir and the Arabic muhajir, both meaning ‘refugees’]. The name, hence, stems from the very history of the quarter: established on the erstwhile outskirts of the city by Muslim refugees fleeing Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Herzegovina Uprising (1875-1877) and the Sanjak of Niš during the Serbian-Ottoman War (1876-1878), it soon gained traction and popularity as it was the closest neighbourhood to the Skopje station of the new Thessaloniki-Mitrovica (Kosovo) railway built in the late 1870s. The proximity to the station defined the district’s life already as of the following decade, and many chronicles note that some of the most beautiful stores and houses on the right bank of the Vardar River were erected in Madžir Maalo.

My project aims at reflecting the history of the neighbourhood, and especially the history related to the migrations of its inhabitants, by closely observing a family house in Madžir Maalo. Once inhabited by a Muslim family, the house has been recently demolished.

What is left for me is to speak from the perspective of the individual elements that remain living in the space, and from memory, in order to briefly narrate the demolition scenario.

Walking down Ante Hajimanov Street, almost at the very end, one might have noticed high brick walls. Through the cracks in them, they may have seen a beautifully arranged courtyard and a free-standing house placed so that it opened completely to the greenery of the courtyard. The house itself had a symmetrical plan, from which one could clearly read the division of the male and female parts in accordance with the religious practice reflected in the architecture. The façade was made of precisely cut stone. In some parts, there was a relief decoration painted in strong, bright colours. They have faded over time, and some have completely disappeared, as has the memory of this house.

After the two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the First World War (1914-1918), Skopje became the administrative centre of Vardar Banovina region in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. The new political constellation of powers translated into a new migration dynamic in the district. The new authorities introduced a policy of settling Serbs and Orthodox Christians in the city of Skopje to change its population structure. This, in turn, resulted in the demolishing of the mosque in the neighbourhood and name changes of all its streets, while the Muslim inhabitants were forced to leave their houses in several migration waves: most notably, many locals left to north and central Albania after the establishment of the Republic of Albania in 1912, while as of the 1910s and up until the early 1950s, the majority of the settler families migrated to Turkey.

Kalina Trajanovska has just graduated from the Faculty of Architecture in Skopje, where she works as a teaching assistant. Apart from conducting academic research, she also takes part in artistic projects.

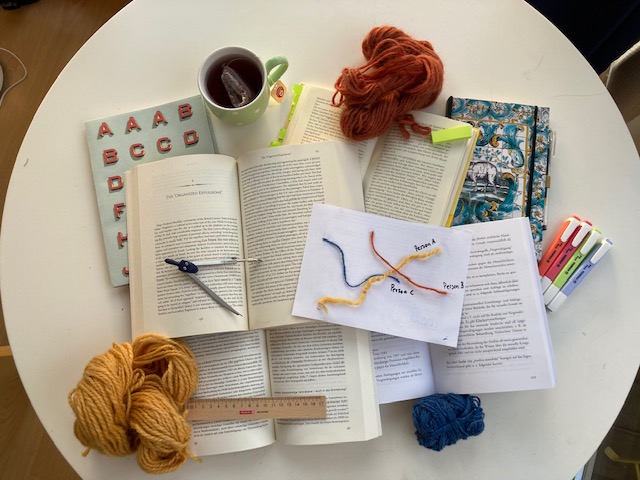

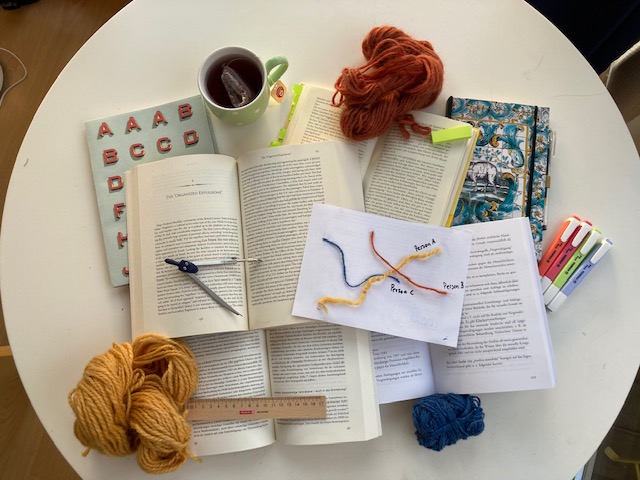

Brenna Yellin

Disorderly Trajectories

My project focuses on ethnic Germans who were expelled from parts of eastern Europe during and after the Second World War and who first arrived in the Soviet Occupation Zone (German acronym: SBZ). Until now, maps have provided a simple and static picture of forced migration. However, flight narratives are anything but simple. Some ethnic Germans, such as Person 1 on my map, were expelled during the early years of the war as part of Hitler’s Heim ins Reich programme; others only fled after the end of the war. With the help of a date slider, this map illustrates that ethnic Germans were not all fleeing at the same time, but rather went through different stages of flight. This map also shows that once the flight began, it did not have a predictable end. Some experienced a quick flight to their destination, while others spent years in forced labour camps, waiting to be transported to Germany. No two flight stories are the same, and this project helps illustrate the differences.

The map allows one to view all eight flight paths simultaneously or to pick individuals and follow their journey more closely. Hovering over the path reveals the age, date, and location of the individual, as well as any additional notes about their journey. Most of these people were children at the time, as they were the ones who lived to see the end of the GDR, allowing them to openly publish their previously censored stories. One can usually assume they have family accompanying them, but I have noted when/if they are separated from family. There is also a page with direct quotes from the flight narratives. Here, one can click on a person or quote and match it with their journey. Overall, this project is meant to both convey the complicated nature of flight, while also providing a more individualistic and narrative approach than other maps.

Brenna Yellin is a PhD student at the Rutgers University (USA) and she was a Visiting Fellow at Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam (Germany). She specialises in modern European history.

Mentor

Polish curator, photographer, lecturer and organiser of art events, as well as promoter of collecting photography in Poland. She graduated from the Institute of Creative Photography at Warsaw Technical University and at the Silesian University in Opava, Czech Republic, where she did her PhD

Katarzyna Sagatowska, PhD

Interested in the topic of interrelation between photography and memory – currently she is working with Max Houghton and Kateryna Radchenko on a Polish-British-Ukrainian exhibition devoted to this subject in the context of historical memory.

Co-author and co-coordinator of the We Are All Photographers (Wszyscy Jesteśmy Fotografami) series – an accessible and friendly guide to the world of contemporary photography, featuring thematic meetings, film screenings and workshops for children.

Scholar of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the City of Warsaw. Jury member in such contests as Young Creative Chevrolet, BZ WBK Press Foto, ShowOFF of Krakow Photomonth and Photographic Publication of the Year (Fotograficzna Publikacja Roku). Author of solo exhibitions and participant in numerous group exhibitions in Poland and abroad.

Founder and owner of JEDNOSTKA – gallery and publishing house.

Photo: Adam Kuchna

Gallery