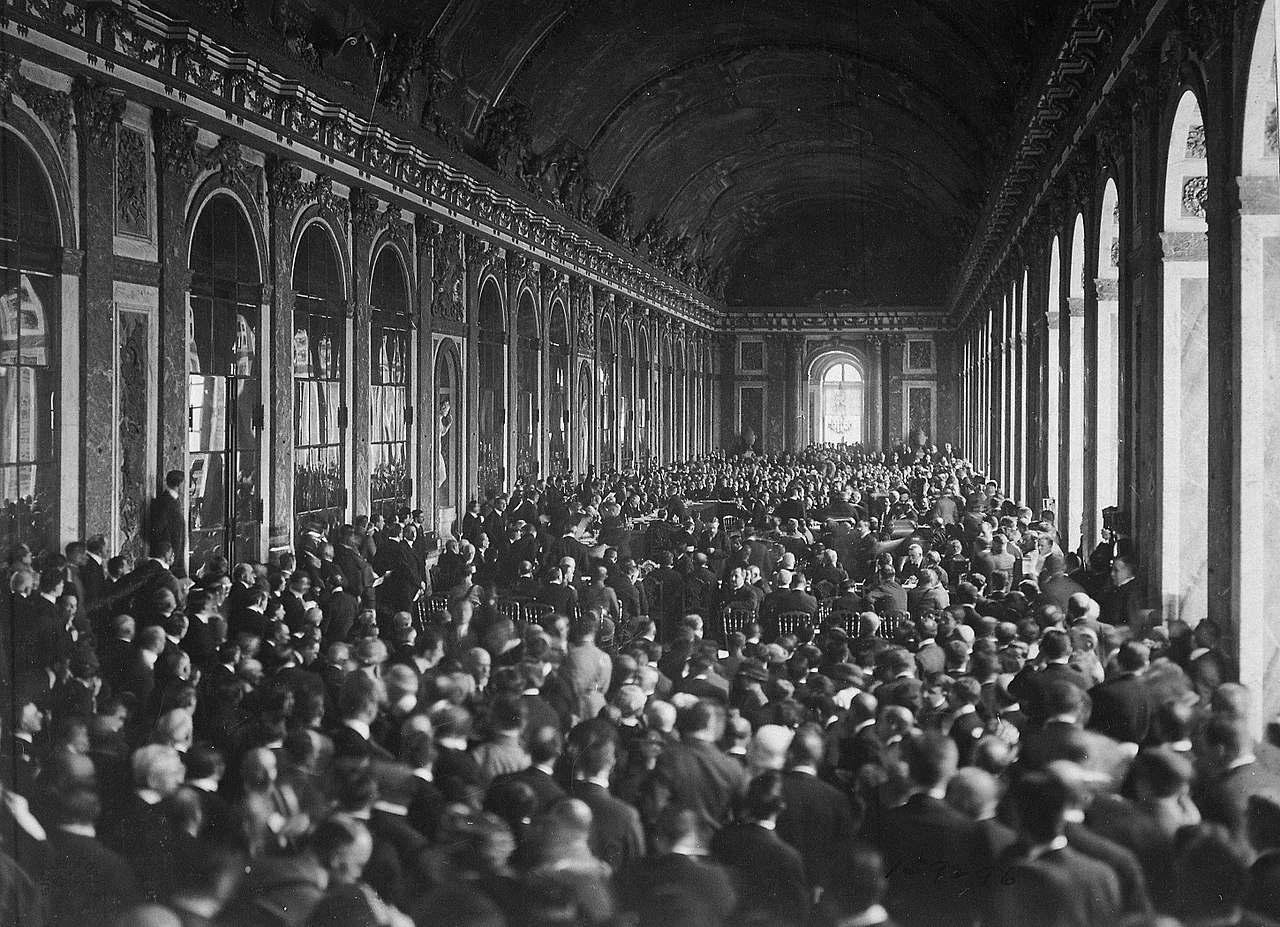

On 28 June 1919, a German delegation entered the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles to sign what was to be known as the Versailles Treaty – the peace agreement ending the state of war between defeated Germany and the victorious Allied Powers. However, before they could enter the room, the German representatives had to pass a group of five French veterans with drastically disfigured faces seen as living proof of German guilt. The scene perfectly epitomised the common sentiments underlying the shape of the Versailles Treaty, a peace agreement to a large extent forgotten, even though its outcome affects Europe to this day and remains highly controversial.

The Versailles Treaty setting the conditions of Germany’s defeat was the first of several peace agreements signed as a result of the Paris Peace Conference, which took place from 18 January 1919 to 21 January 1920. The aim of proceedings was to officially end the First World War and create a new order in Europe. It was to prevent any future armed conflicts, draw new borders and settle reparations at the expense of the defeated Central Powers. The talks were led by the Council of Four (briefly preceded by the Council of Ten), which included US President Woodrow Wilson, French Prime Minister George Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, representatives of the most prominent countries among the victorious Allied Powers. The Council was also supported by 52 expert commissions. Those who lost, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire, were not invited to the table and were expected to simply comply with the given conditions first formally articulated in the Versailles Treaty.

One of the most difficult issues influencing the Paris Peace Conference was, paradoxically, not how to reach a compromise between victors and losers, but among the victors themselves. The French, who had their north-eastern territories ravaged by war and lost one quarter of men age 18-27, set out to punish Germany. The British, on the other hand, feared French domination and were in favour of maintaining a balance of power on the continent, also due to economic reasons. Meanwhile, President Wilson sought to establish the upcoming European order on self-determination of nations and sought to ensure the new world order by creating an inter-governmental organisation known as the League of Nations.

For long, the German delegation was not aware of the issues discussed and conclusions reached, thus the final harsh shape of the treaty took it by surprise. Among its many points, the Versailles Treaty assigned full responsibility for the First World War (so-called war guilt) to Germany and its allies. The German army was restricted to 100,000 men and no air force, tanks, armoured cars or submarines were allowed. War reparations were to be fixed later. The sums varied over time. In 1921, liability was finally set at 132 billion gold marks (approx. 470.61 billion current US dollars). Most of the navy and the bulk of merchant shipping was to be delivered to Great Britain. Territorial changes, including, but not limited to the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to France, province of Posen/Poznań and a large part of West Prussia to Poland, Eupen-Malmedy to Belgium, signified a loss of roughly 13% of Germany’s territory before 1914. Germany also lost all its colonies.

In Germany, the Versailles Treaty was perceived as a humiliation. German Prime Minister Philipp Scheidemann resigned and parliament managed to approve the treaty only 80 minutes before the deadline after which the start of a new war was to be expected. Even after being accepted by the government, the peace conditions were constantly challenged by various revisionist movements. This was in spite of other defeated countries incurring even worse peace terms. In order to understand the mood within German society, we must remember that Matthias Erzberger, the politician earlier who signed the armistice on 11 November 1918 on behalf of Germany, was murdered for this act by right-wing soldiers. The subsequent success of Adolf Hitler was also to a large extent founded on criticism of the peace treaty. Contradicting the “diktat” of Versailles remained a key provision of German foreign policy in the interwar period. Only the Second World War managed to erase the Versailles Treaty from the German collective memory, but not before the victorious Third Reich made the conquered French army sign the armistice of 1940 in the same train carriage, in which the German delegation had to sign the armistice in 1918. Poland, which benefited from the treaty, rather emphasised its own achievements in regaining its independence. In particular, it was forced to sign the Minority Peace Treaty, a part of the Versailles Treaty, that secured minority rights. In Hungary, on the other hand, the Paris Peace Conference, particularly the Trianon Peace Treaty, are still recalled as a traumatic experience.

Harsh conditions imposed on the losing side in a short-sighted manner were only one of the issues relating to the Versailles Treaty and other peace agreements signed as a result of the Paris Conference that continued to raise controversy. Another was the rule of self-determination that mainly served the victors, while leaving other groups excluded. It is often said that it was precisely due to this dissatisfaction that the Paris Conference did not achieve its aim of preventing future armed conflicts. Nevertheless, it should not be overlooked that the post-war order was also weakened by hyperinflation and the economic crisis of 1929-1935, as well as the American withdrawal from supporting the League of Nations. These were only some of the problems that arose when all the delegates left Paris.

Another popular view about the Paris Conference and its treaties is that they created nation states, as many Central and Eastern European nations were able to (re)establish their own countries following the break-up of the four pre-war grand empires. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the states that emerged, such as Poland, Czechoslovakia or Yugoslavia, were in fact multinational in character, a matter that is often forgotten. Moreover, although one cannot underestimate the importance of the decisions made in Paris, the new order was to a large extent shaped simultaneously by the respective Central and Eastern European nations through the active use of political and military means. Thus, some of the agreements drafted in the French capital only confirmed already initiated changes, while in other instances the Paris decisions failed to ever be executed. Nevertheless, the victorious nations of East-Central Europe, by sending their envoys, could for the first time in their history, at least to some extent, speak for themselves.

Even with all controversies and collective memories filled with contradictions and omissions, one thing remains certain. The Versailles Treaty and the remainder of the Paris agreements created a new order whose remnants and consequences still shape the Europe of today.

Bibliography:

W. Borodziej, ’Wersal, Jałta i Poczdam. Jak problem polsko-niemiecki zmienił historię powszechną’, in: ‘Paralele’, in: Polsko-niemieckie miejsca pamięci, v. 3, H. H. Hahn, R. Traba, cooperation: M. Górny, K. Kończal, Warszawa 2012

R. Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1923, New York 2016

H. Konrad, ‘Drafting the Peace’, in: ‘The State’, in: The Cambridge History of the First World War, ed. J. Winter, Cambridge 2014

J. Leonhard, Die Büchse der Pandora. Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs, München 2014

A. Sharp, The Versailles Settlement. Peacemaking in Paris, 1919, London 1994