This article appeared in the Polish weekly Polityka, issue 51/52 (3545), on 16 December 2025. The original title: “Ikona z torebką.”

The woman who struck a neo-Nazi in Sweden became a symbol of civic courage, resistance to nationalism, and an inspiration for mass culture. For a long time, she remained anonymous. It turned out she was Polish.

It was Sunday, 13 April 1985. In the sleepy town of Växjö in southern Sweden, home to 60,000 people, something was finally happening. At 11:00 a.m., supporters of the left had called a demonstration on Stortorget (the main square); an hour later, members of the Nordic National Party (Nordiska Rikspartiet) were to demonstrate.

Both had received permission from the authorities. Such events usually passed without incident. In the mid-1980s, Swedes enjoyed a high standard of living and social calm; politics still seemed like a boring idyll (Prime Minister Olof Palme was assassinated a year later). The residents of Växjö did not necessarily share the demonstrators’ views, but they acknowledged their right to demonstrate, and so they watched passively as a dozen or so neo-Nazis marched through the city, shouting racist slogans. At the intersection of Norrgatan and Kronobergsgatan, one of them (waving the flag of the Nordic Reich) was suddenly approached by a woman in a short coat and a pleated skirt. And she struck him on his shaved head with her handbag.

The Perfect Shot

The woman’s gesture acted like a detonator. Insults and eggs flew toward the demonstrators, and then the crowd surged forward. Several neo-Nazis were injured in direct clashes; one was beaten unconscious and only saved from a fatal lynching by a left-wing activist. In the end, the neo-Nazis fled. According to SVT Nyheter, they found refuge in the toilets at the railway station, from where they were escorted by police, who had to call in reinforcements to control the crowd. The disturbances shocked Swedish public opinion, unaccustomed to physical aggression in politics. This shock also had its detonator: a photograph by Hans Runesson.

The reporter for Dagens Nyheter, one of the country’s largest newspapers, pressed the shutter at the moment the handbag landed on the neo-fascist’s occiput - just as in the concept of the “decisive moment” formulated by the father of photojournalism, Henri Cartier-Bresson. This is a key principle of reportage photography: the intuitive capture of a fraction of a second in which action, composition, and emotional expression converge to form perfect harmony within the frame. The photograph was named Photo of the Year (Årets Bild 1985), and later the Swedish Association of Historical Photography recognised it as Photo of the Century.

The image lives on today, taking on a life of its own: as an icon of the fight against neo-fascism, it has appeared on T-shirts, graffiti, banners, and tattoos. On the other hand, voices emerged from the realm of political correctness taken to the point of absurdity - claiming that the woman had “brutally attacked an innocent protester”.

„We were wondering if publishing the photo does not increase the risk of the woman being accused of assault, since she could be identified easily”, recalled Anita Bengtsson, then editor-in-chief of Dagens Nyheter. Journalists flocked to Växjö to find the heroine of the photograph, but she gave no interviews. According to Swedish media, she feared retaliation from nationalists (some sources say her family was under police protection for a time). She was also reportedly unhappy with how she appeared in the photo: she was only 38 years old, yet the public saw her as a grimacing tant - a stereotypical “auntie” who likes handicrafts, walks, and gossip.

Today, the term tant can symbolise authenticity, civic courage, quiet wisdom, and an ethical compass in a world dominated by fashion, status, and appearances. There is even talk of tantpower – the strength of women who no longer have anything to prove to anyone – but the “woman with the handbag,” as she was called, did not live to see that shift.

Three years after the neo-Nazi march, she jumped from a water tower in Växjö. According to journalists’ findings, the suicide was rooted in earlier mental health disorders, though the uproar surrounding her person may have contributed. Her son said at the time that she disliked the photograph and the publicity it brought. He criticised both anti-fascists and nationalists for exploiting his mother and denied rumors that she had been mentally unstable when she struck the protesters.

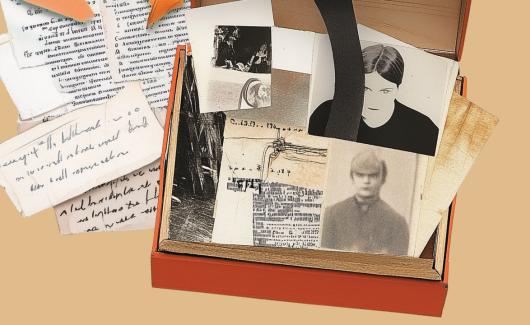

Where did such a powerful impulse came from- one that was able to pull the "woman with the handbag" out of the crowd? Speculation intensified when her identity came to light. Swedish media reported that her name was Danuta Danielsson. She was a Pole who married a Swede in the early 1980s and emigrated. At the demonstration, she reportedly lost her temper because her mother was said to have been a Jewish woman imprisoned in a German concentration camp in occupied Poland. This narrative appeared in every publication - and there were many thanks to sculptor Susanna Arwin, who in 2014 created a miniature statue based on Runesson’s photograph.

This led to an initiative to create a life-size sculpture and place it in Växjö on the 30th anniversary of the events. More than 11,000 people signed in support, and the debate reignited over whether the monument would glorify “political violence”. “We in Växjö work for democracy and free speech. Of course, we don't like Nazis. But we can't accept that one can hit a person because one does not like him or her”, said city councillor Eva Johansson, quoted by The Washington Post. The American journal also cited a comment by writer Ola Luoto for Dagens Nyheter: “What [Johansson] forgets it that art is multi-layered and open to different interpretations. [Danielsson] was undeniably one of the real victims of the Nazis. The fact that she got enraged is understandable”.

Handbags on Monuments

From a protocol obtained by Polityka from the municipality of Växjö, it emerges that, at the request of Councillor Johansson, the city’s Culture and Leisure Committee withdrew its earlier approval for the monument, also due to the lack of consent from a member of Danuta Danielsson’s family. “In the previous term, attempts were made to locate relatives of the woman depicted in the photograph, but no one could be found. Now, however, a close relative has contacted us and opposes the erection of a monument depicting this woman,” we read.

The decision by Växjö councillors sparked a wave of outrage. In protest, women’s handbags were hung on monuments across the country and photos of them shared on social media. A handbag was also placed on the statue of one of the country’s greatest national writers - Astrid Lindgren, author of the iconic series of novels about Pippi Longstocking. News of this spread around the world, and local politicians declared their willingness to install the monument in their own cities. “It looks fantastic, and the photo is iconic. Although this monument should belong to Växjö, because the incident took place there, we’ll take it if they don’t want it,” said Nils Karlsson, a representative from Malmö.

Ultimately, sculptures based on Runesson’s photograph were installed in the cities of Alingsås and Varberg. In Växjö - though not on Stortorget, as planned, but on the university campus - another monument by Susanna Arwin was erected, titled Den Svenska Tanten (The Swedish Aunt): a woman standing politely with a handbag slung over her shoulder. The website dedicated to it states that it is part of an artistic project that was created in 1995, guided by the slogan “Dare to be ordinary.” Not a word about the immigrant from Poland.

Even more surprising may be the silence of the family. Her son guards his anonymity, and Polish relatives never sought to commemorate Danuta. “There’s nothing to talk about!”, snaps her nephew angrily over the phone. A Polityka reporter finds him in Poland, in the Zamość region. His mother (who also refuses to talk about it), the only surviving sibling of Danuta out of four, lives in the same village. A second sister died shortly after birth. Two brothers lived until their deaths in the 2000s in Gorzów Wielkopolski, as did Danuta before she emigrated to Sweden. This city of 110,000 readily boasts of former and current residents who have gained fame at home or abroad - but it consistently omits Danuta. Does her story therefore have a hidden second layer?

Codename Trio

Apartment no. 5 in a neglected post-German tenement at 19 Strzelecka Street in Gorzów was Danuta’s last Polish address (she lived there for 16 years), but current tenants have never heard of her. In the civil registry records comes the first surprise - althoug a minor one: upon marriage, she did not give up her maiden name. Thus, her full name was Danuta Seń-Danielsson. To this day, the registry office has not received information about her death.

According to The Washington Post, she reportedly regretted striking the neo-Nazi almost immediately. This may indeed have been the case, though not necessarily due to remorse. In response to Polityka’s questions, Swedish police confirmed that 40 years ago they conducted an investigation into her “assault.” It was launched only five months after the demonstration, in September 1985, so the complaint was likely filed by neo-fascists seeking political gain. “The investigation was concluded and forwarded to the prosecutor, but I do not know whether charges were brought against Mrs Danielsson afterward or not,” wrote Martina Alma, a police archivist. The trail ends there.

We also attempted to verify the camp past of Danuta’s mother. There is no trace of her in the Arolsen Archives (the world’s largest archive of data on victims of German National Socialism and survivors), nor in the IPN (the Polish Institute of National Remembrance) database (

straty.pl), nor at the Auschwitz Museum (this camp was mentioned in some press publications). We find her thanks to a query conducted by Anna Wójcik, head of the archive at the State Museum at Majdanek. Some details do not match, but the unusual name (Prakseda), place of birth, and place of residence (the same village where Danuta’s sister still lives) indicate that her mother was indeed imprisoned by the Nazis. Probably not at Majdanek (too many details do not fit), but the local archive contains a form filled out in 1964 by her husband and Danuta’s father for former prisoner Prakseda Seń (she was “barely literate”).

Arrested on 20 July 1941 for participation in the partisan movement (as a courier), supplying partisans, and “for hiding Jewish children and women and providing them with food” (Prakseda Seń did not claim Jewish origin but could “speak Jewish”). Initially imprisoned in Nowogródek. From October 1941 in concentration camps - she lists Majdanek, Dachau, and Mauthausen. “I miraculously escaped death by burning and gassing; I was a guinea pig for experiments,” she dictated to her husband. She was beaten and abused; “SS doctors” forcibly bound her arms and legs, “took enormous amounts of blood,” and “administered experimental injections” (original spelling). When the Allies liberated the camp (no name given) in March 1945, she was ill and exhausted, maimed and starving. She required six months of treatment, and in February 1946 the Polish Red Cross transported her to Poland. The form does not mention it, but there was also France along the way: in the summer of 1945, Danuta’s still-living sister was born there.

So there is nothing here that would explain the family’s distance from commemorating Danuta - quite the opposite. The explanation may lie, however, in what we find in the IPN archives, specifically in the files of an “operational verification case” under the codename Trio.

The so-called Trio consisted of three people: Danuta Seń-Danielsson, her husband Björn Danielsson, and her father Jan Seń, who traveled to Växjö at his daughter’s invitation. He was to spend three months there, but after only two, at the beginning of March 1984, he went to the police and reported that his daughter and son-in-law had taken his passport to prevent him from returning to Poland and to force him to apply for political asylum. Officers spoke with Björn, who denied it, and that ended the matter for the local police. The father, however, did not give up: he went to the Swedish Red Cross headquarters for assistance, as he had left his daughter’s home without clothes or money, and then to the Polish consulate, where he applied for a new passport.

Under the former system, this was no trivial matter. The document did not belong to the citizen: “This passport is the property of the Polish People’s Republic,” stated the note on its cover. Citizens did not keep passports at home. They were stored at communist militia stations and later at passport departments of the Security Service and were issued only for a specific trip. Permission to travel depended on so-called environmental inquiries, even opinions from the workplace or the security services, and upon return the citizen had to surrender the passport. Its loss therefore set consular services in motion: the IPN files contain an urgent telex stating that citizen Jan Seń had reported to the consulate without a passport. He also complained that he had not been fed properly at his daughter’s home and that he had been beaten. He was issued a so-called blank passport (temporary), put on a ferry to Świnoujście, and the Security Service took the case under scrutiny.

Intimate Contacts

Had Jan Seń sold the passport or handed it over to someone? If so, for what purpose? Had he lost it? For what purpose might his Swedish son-in-law have taken it? What role did Danuta play in this? Was it really about forcing him to apply for asylum? These questions were entered into the justification for opening the case codenamed Trio.

The “operational verification” lasted as long as three years. It was conducted by the Second Department of the Provincial Office of Internal Affairs in Zamość and involved other departments and offices dealing with the surveillance of foreigners (including in Gorzów Wielkopolski and Wrocław), as well as militia units. The Security Service activated secret informants. Neighbors and acquaintances of Danuta, her parents, and siblings were questioned. The Danielssons were surveilled when they came to Poland. Those who had contact with them were interrogated - even a taxi driver who drove them on New Year’s Eve. Among Poles traveling to Sweden, individuals were selected who might have contact with them and report on them. The past and beliefs of the entire family were scrutinised. The identity of the father of Danuta’s illegitimate son was established (the boy was eight when she married Björn). The father was a physician from Gorzów Wielkopolski (another person is listed as the father on the birth certificate), and the boy was born in the Lublin region. Danuta’s career path was analyzed: from nurse and orderly at the Gorzów Wielkopolski hospital, to manual worker at the Stilon fiber factory, to making coffee at a student club in Växjö and occasional work as a cook at the local hospital.

Björn was said to have arranged the latter job for her. Earlier, she had received a Polish disability pension, but it was suspended when Danuta left the country permanently in August 1982. She received permission to travel as the wife of a foreigner. They married on 21 November 1981 in Gorzów Wielkopolski. Björn, a journalist at a Växjö radio station, was 22 years older than her. They reportedly met shortly before the wedding - at a music festival, according to other sources during a Baltic Sea holiday. “At that time he did not know about her past,” noted one Security Service document.

“As established through operational findings, she is a woman of loose morals, maintaining for many years extensive intimate contacts with men, mainly foreigners, for which she also received material benefits,” reads a security service note about Danuta Seń-Danielsson. In others: “She actively practiced prostitution throughout the country,” “She maintained numerous contacts with foreigners arriving for the International Trade Fairs in Poznań. They were mainly traders from the West Germany”. At the Orbis-Panorama hotel in Wrocław in the late 1970s, she met with the secretary of the Finnish Embassy in Warsaw. The files record his name, room number, and meeting time. There was also a second “intimate meeting” with the Finnish diplomat, for which she allegedly received 400 dollars. “Currently, she also proposes intimate contacts to most men she meets, not concealing this from her husband,” an officer wrote. Similar accounts were repeated by her acquaintances and the taxi driver who drove her in Poland.

The “operational verification” ended when Danuta’s father died, followed shortly by her mother. Due to their deaths, the Danielssons would no longer have anyone to visit in Poland, since Danuta “lives in conflict with her extended family and maintains no contact” with them, as noted in the analysis. The materials indicate that the Danielssons consumed alcohol “in excessive quantities” and frequently held drinking parties during which she boasted of having married a Swede for money and an inheritance, and of intending to return to Poland with her son after his death. Danuta eagerly told security officers about named Polish acquaintances in Sweden, including those staying illegally, and about their views on the political system and Poland. She declared a willingness to cooperate with the security service, even “thrusting information upon us that might interest us,” as the case officer observed. “The subject was twice treated in the psychiatric hospital in Radecznica. Due to her health condition – a nervous illness – she is not suitable for operational use,” he noted.

It was not established that any of the Trio engaged in activity hostile to the Polish People’s Republic or the system; the state also recovered Jan Seń’s passport (the daughter sent it back to the consulate). The case was therefore archived as “fully clarified.” Before that happened, the memorable demonstration of 13 April 1985 took place in Växjö. A few months later, on 25 August 1985, Seń-Danielsson described it in a protocol of the Security Service. This is most likely her only documented statement on the matter.

The Verdict

“A fairly large group of residents, mainly foreigners permanently residing there, attacked the participants of this march. Among the group attacking the neo-fascist gang was the interviewee, and her photo was to appear in many Swedish newspapers,” noted Lt. Zygmunt Wojciechowski. “As Danuta Seń claims, in Sweden there are quite a lot of such [neo-fascist] groups and they derive from young Swedes, because Swedes do not regard Hitler as a criminal but as a defender of the German nation, who sought to remove foreigners from the country (mainly Jews), who were a burden to Germans. Swedes currently also believe that foreigners are a burden to them, as they do nothing, and that they should somehow be gotten rid of, even with the help of neo-Hitlerite groups. People who were in concentration camps - and there are very few of them in Sweden - consider these groups dangerous and threatening to world peace.”

The man Danuta struck with her handbag proved dangerous indeed. Seppo Seluska, shortly after the famous photograph was taken, murdered a gay Jew, first torturing him. In 1992, he attempted to drown a person of Arab origin in a particularly brutal manner. The victim survived but suffered serious injuries. In 1995, Seppo Seluska was again involved in the murder of a gay man. In 2004, he murdered another person, after which he was sentenced to life imprisonment and is currently serving his sentence.