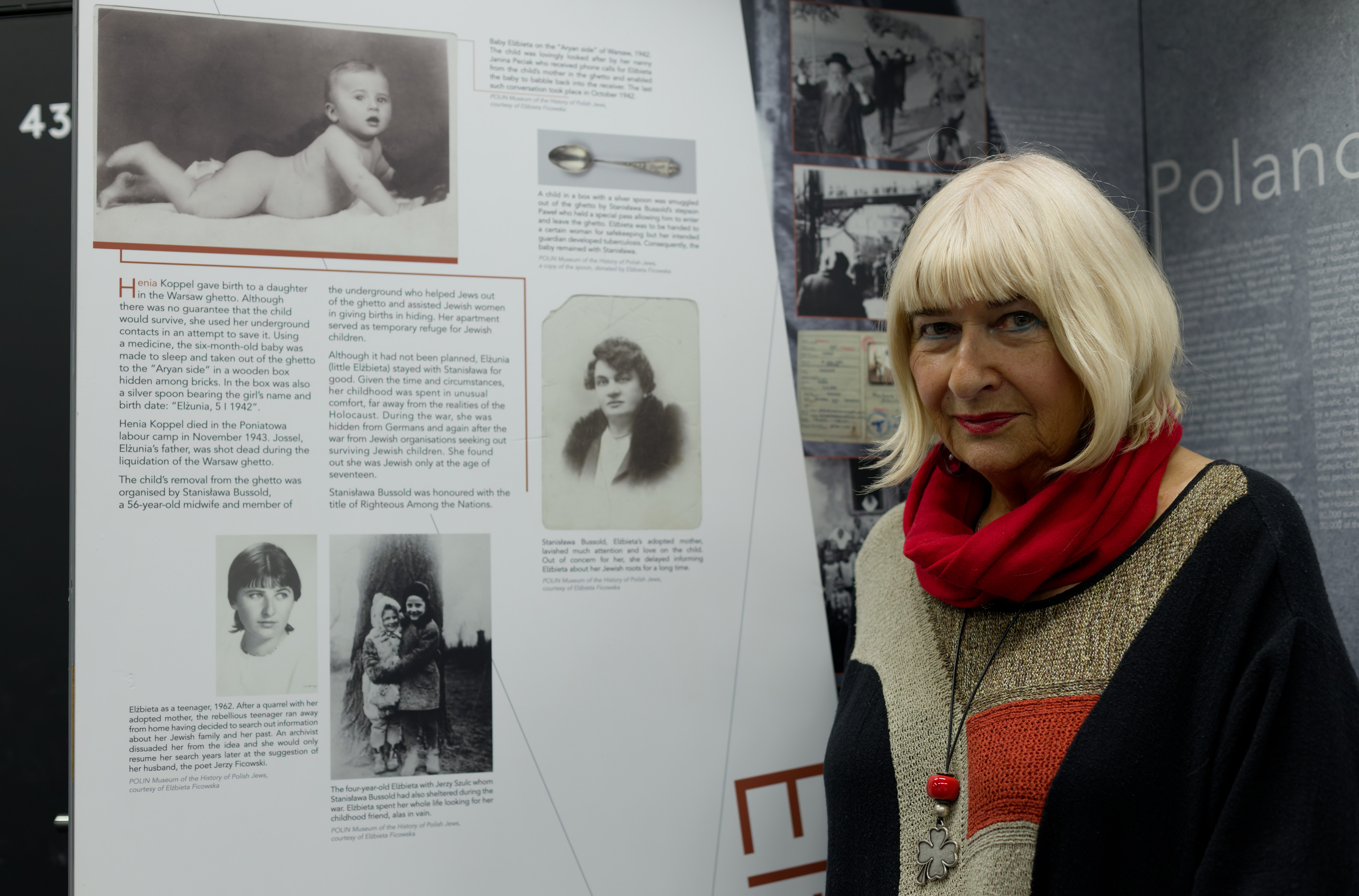

She was already 17 when she accidentally learned that everything she knew about herself was untrue. That the mother she was with, Stanisława Bussoldowa, did not give birth to her at all, but took care of a six-month-old baby, saved at the last moment from annihilation in a world that no longer existed. That Elżunia was not after all a diminutive of Elżbieta (Elizabeth), but a Jewish name, in Hebrew, Elishew. This name, as well as her likeness, was left by Henia Koppel, a Jewish woman, Elżbieta Ficowska’s ‘real’ mother, whose face Elżbieta never knew.

Born under an imprisoned star

Elżbieta Ficowska’s mother, Henia Koppel, gave birth to her in the Warsaw ghetto. To save the child, she decided to move her to the Aryan side. The six-month-old baby was given medicine to sleep, placed in a wooden box with holes in it so she could breathe, hidden among the bricks and taken away from the Warsaw ghetto. The box also contained a silver spoon on which was engraved her name and her date of birth: ‘Elżunia, 5 I 1942’, the only trace of a surviving identity.

Elżbieta has no idea what her parents looked like. She has no photographs. Years later she managed to track down two of her mother’s friends from grammar school, who described her mother as a beautiful blonde with blue eyes. Her father was much older, stocky, black-haired and black-eyed. This is the only image she has of them.

‘I have seen so many photographs of nameless Jews in old German film chronicles. I always stare at them searchingly, and sometimes I succumb to the illusion that I might somehow recognise my loved ones, even though I know it is impossible. I don’t know their faces, I only see them in my imagination’, she later said in an interview.

From that world to this world

The child was taken out of the ghetto by Stanisława Bussoldowa’s stepson, Paweł Bussold, who had a pass to the ghetto. Elżbieta was supposed to go to a woman, but the latter fell ill with tuberculosis. Although she had not planned to, Bussoldowa took good care of Elżunia. During the years of German occupation, she provided assistance to Jews from the Warsaw ghetto, collaborating with Irena Sendler. Stanisława Bussoldowa worked as a feldsher and midwife at a health centre on Działdowska Street in Warsaw. The facility organised money for Jews locked behind the walls of the Warsaw ghetto. She also delivered food ration cards to the ghetto, took people to the so-called Aryan side and delivered babies of Jewish women hiding in occupied Warsaw.

On a daily basis, the young girl was looked after by a nanny – Janina Peciak. She would receive phone calls from the child’s mother from the ghetto and put the receiver to the chattering little girl. The last time she called was in October 1942.

Henia perished on 3 November 1943, in the forced-labour camp in Poniatowa. Elżbieta’s father, Josel, perished during the major liquidation operation of the Warsaw ghetto (July–September 1942). He was shot at the Umschlagplatz when he refused to get into a wagon. They were disappeared like the world she had never managed to get to know and had no chance to know from the Aryan side.

Washed you of orphanhood and swaddled you in love

As Elżbieta Ficowska recalls, her foster mother offered her a happy childhood full of love. When Stanisława Bussoldowa took in Elżunia, she was already in her 60s; her children were grown up and she herself was a widow already. She gave her foster daughter a lot of wholesome and mature love. She was a well-looked after child, and everyone around her did their best to make her feel as comfortable and as safe as possible. This is why Stanisława Bussoldowa protected her from a premature clash with history. Out of concern for the child, Stanisława Bussoldowa did not allow Elżbieta to find out about her Jewish origins for a long time. During the war, she was hidden from the Germans. After the war, she was also hidden from the Jewish organisations seeking to recover the children who had been saved.

Not to be surprised at all when you say – I am

Elżbieta Ficowska found out about her Jewish origins at the age of 17 by accident. A friend, with whom she attended the Felician Sisters’ School in Wawer, asked her one day why she hadn’t told her she was Jewish. Elżbieta thought it was nonsense, completely untrue. However, this information planted a seed of anxiety in her, and her imagination increasingly suggested videos from the past and various, as well as strange stories. Such as the one from when she was in the cemetery and noticed that the date of her father’s death, Stanisława’s husband, died two years before she was born. She was then told that the stonemason had got the date on the gravestone wrong, and she did not pursue the story further.

In the same way that she didn’t make the connection, while she was with her nanny in a vegetable shop in Michalina, when someone asked her if the Jews coming from America had already been there. She had no idea that after the war there were Jews in Poland who wanted to find the Jewish children rescued from the Holocaust and take them to Jewish families in America or Israel.

Eventually Elżbieta Ficowska learned about her Jewish background from her Polish mother. After an argument, she ran away from home to a friend’s house. She hid in the basement and refused to come out. When she was found by her mother, they had their first and only conversation about how she became her daughter. ‘It was so difficult for her and for me that we never went back to it again,’ Elżbieta Ficowska confessed in an interview.

I keep both my mothers with me

Henia Koppel (1919?–1943) and Stanisława Bussoldowa (1886–1968) were both mothers to Elżbieta Ficowska. The first, who gave her life ‘under an imprisoned star’, gave up her daughter in order to save her life, and the second spared her of orphanhood and swaddled her in love. Both risked their own lives.

‘I keep both my mothers with me and will do that till the end. Their presence reminds me that there is nothing more destructive than hatred and nothing more precious than human kindness,’ says Elżbieta.

A tribute to both of them is a poem by Jerzy Ficowski, poet and husband of Elżbieta Ficowska. ‘Both Your Mothers’ is dedicated to Bieta, as Jerzy affectionately addressed his wife by this nickname, and commemorates the story of two mothers, two maternal loves, and is a monument to their sacrificial love.

***

Both Your Mothers

for Bieta

Under a futile Torah

under an imprisoned star

your mother gave birth to you

You have proof of her

beyond doubt and death

the scar of the navel

the sign of parting for ever

which had n time to hurt you

this you know

Later you slept in a bundle

carried out of the ghetto

someone said in a chest

knocked together somewhere in Nowolipie Street

with a hole to let air in

but not fear

hidden in a cartload of bricks

You slipped out in this little coffin

redeemed by stealth

from that world to this world

all the way to the Aryan side

and fire took over

the corner you left vacant

So you did not cry

crying could have meant death

luminal hummed you

its lullaby

And you nearly were not

so that you could be

But the mother

who was saved in you

could now step into crowded death

happily incomplete

could instead of memory give you

for a parting gift

her own likeness

and a date and a name

so much

And at once a chance

someone hastily

bustled about your sleep

and then stayed for a long always

and washed you of orphanhood

and swaddled you in love

and became the answer

to your first word

That was how

both your mothers taught you

not to be surprised at all

when you say

I am

[translated by Keith Bosley]