Nazis are still being prosecuted in Germany; however, many have never been tried due to political considerations and society’s reluctance to come to terms with the past.

It is difficult to imagine a greater turning point in the life of a nation than that experienced by Germany after the end of the Second World War. Unconditional surrender, occupation and the rule of foreign powers went hand in hand with the breakdown of German notions of their superiority and power. However, society could not dissociate itself from a closed historical chapter, since it faced the colossal problem of coming to terms with the ideology and crimes of National Socialism. 7.5 million members of the Nazi Party, 850,000 members of the SS, newsreels across the world showing heaps of corpses in liberated concentration camps, perpetrators of crimes against humanity, including the Holocaust, blending into the crowd and keeping a low profile, doctors killing en masse the disabled and the terminally ill, a corrupt judiciary, youth brainwashed by Nazism – this was only a fraction of the burden under which German society began to build its future. At the same time relatively few people in Germany were aware of the scale of the problem and for certain no-one had any idea of how to solve it.

Nuremberg Known and Unknown

Aware of the immense support that Hitler’s regime had enjoyed in German society, the Allies doubted the Germans’ ability to cleanse themselves. Therefore, as early as in 1942 they took on the responsibility of punishing those charged with war crimes, and ordered the relevant documentation to be drafted. In November 1943, it was decided that those charged with war crimes were to be extradited to the countries where they had committed their atrocities, and those whose deeds concerned multiple countries – belonging to the category of main perpetrators – were to be brought before an international court. Thus in August 1945, the Allies signed a treaty establishing the International Military Tribunal. It operated during the Nuremberg Trials, where from 20 November 1945 to 1 October 1946, twenty-two principal war criminals from the highest levels of the Third Reich were tried. They were selected in a manner assuring a representation of the Nazi system’s main areas of activity (including Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Martin Bormann – Nazi Party leaders; Julius Streicher, Alfred Rosenberg –ideologists of Nazism; Joachim von Ribbentrop, Konstantin von Neurath – foreign policy; Ernst Kaltenbrunner – the SS and police; Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Keitel, Erich Raeder, Karl Dönitz – armed forces; Hans Fritzsche – propaganda; Baldur von Schirach – Hitler Youth; Albert Speer and Hjalmar Schacht – the economy, Hans Frank and Artur Seyss-Inquart – the occupation policy). During the trial, 19 convictions were handed down, including 12 death sentences.

However, an often overshadowed fact is that from 1946 to 1949 twelve other large trials were held in Nuremberg, such as the Ministries Trial (management of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs); the trial of concentration camps doctors (the Doctors’ Trial); Einsatzgruppen; the management of the Kruppa and I. G. Farben companies; the SS Race and Settlement Main Office, and the SS Main Economic and Administrative Department. Oswald Pohl, the head of this key unit tasked with operations including organisation of the concentration camps, was sentenced to death and executed on 8 June 1951 at the American military prison in Landsberg, Bavaria. This was the last execution carried out in the Federal Republic of Germany, since the death penalty had been abolished with the founding of the country in 1949.

Further trials between 1946 and 1951 were made possible due to Law No. 10 of the Allied Control Council, enacted as early as 1945, which expanded the powers of the military governors of individual occupation zones. This law was rescinded in 1951, when West Germany received many attributes of a sovereign state. Hence over several years, the Allied system of courts and prisons across Germany was eliminated. It should be noted that as early as 1950, the USSR had closed down its ‘special camps’ where Nazi prisoners were interned, and completed its prosecution of war criminals in East Germany. The last relict of the post-war period of Nazi war crimes trials was the joint military prison in Spandau, maintained and operated by the Allies, where prisoners sentenced at the Nuremberg Trials were detained. In existence as long as the last prisoner was alive, it was closed in 1987 after the suicide of Rudolf Hess.

In the initial post-war period, a great majority of Germans felt an aversion to the trials of war criminals. Even the Nuremberg Trials failed to exert the psychological effect expected by the occupying powers. It was generally viewed as a form of revenge on the defeated and the belief was that the verdicts of the victors could not be just. Besides, the nascent Cold War meant that friendly relations with the Germans were important to both sides. Thus the enthusiasm of the occupying powers to prosecute the Nazis quickly dampened. Extradition to East European countries was abandoned as early as 1947, and soon the practice of early release for convicts from Allied prisons spread.

In his first address to the opening of parliament in 1949, West Germany Chancellor Konrad Adenauer already spoke about a blank slate when coming to terms with the recent past. Most probably he was convinced that the rebuilding of West Germany would not be possible without the advocates of National Socialism. They were too numerous and too many belonged to the country’s professional elite. For this reason, in the West Germany of Adenauer’s era an unwritten agreement was reached between the new authorities and the advocates of Nazism, under which the authorities guaranteed them impunity (with the exception of a very small group of people charged with the most severe crimes) and freedom of professional development; while they, in turn, renounced their public anti-system and racist activity. The first amnesty act was passed as early as 1949, which freed from responsibility thousands of Nazis convicted for lesser crimes. In 1951, the West German Parliament passed another act, under which they regained public posts (including in the police) in a short period of time. It is therefore no surprise that in the 1950s the number of Nazi war criminals tried by West German courts dropped dramatically.

The Guilt of the Fathers

However, the situation in West Germany changed with the coming of age of the younger generation, who opposed concealing the guilt of their parents’ generation. Gradually, thanks to researchers, knowledge about Nazi Germany and the crimes committed during the period improved. Now and again, wishing to discredit West Germany, the East German security services revealed compromising facts about the Nazi past of West German politicians and high-ranking officials. In an atmosphere of gradually mounting interest in bringing Nazis to justice, the trial of ten members of Einsatzkommando Tilsit (Einsatzgruppe A), who were charged with murdering many thousands of Jews in Lithuania in 1941, gained wide publicity. Despite the fact that each defendant’s personal responsibility for executing at least several hundred Jews by firing squad had been proved, the sentences handed down during the trial, held in Ulm in 1958, ran contrary to the fundamental sense of justice (between 3 and 15 years’ imprisonment).

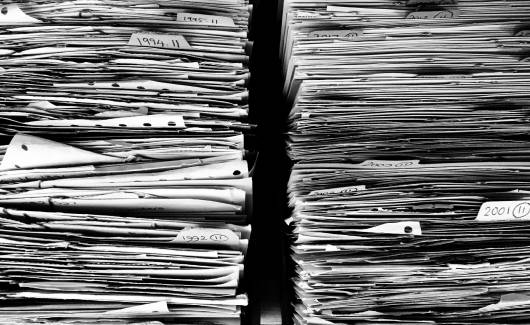

This scandal provided an impetus for the creation in November 1958 of a West German institution specialising in prosecuting Nazi crimes, i.e. the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, popularly called the Central Office in Ludwigsburg. Its operations were restricted in numerous ways, the most important of which was that the prosecutors only had the right to prepare indictments, without the possibility of independently filing these with a court. Despite this, the Central Office established a new quality in the German court system and greatly enhanced the prosecution of Nazi crimes in West Germany. To date it has drafted around 7,500 indictments.

Successive breaches in the wall of silence behind which the Germans were hiding came from the exhibition Ungesühnte Nazijustitz, shown for the first time in Karlsruhe in 1959. It proved that tens of highly-placed West German lawyers were guilty of severe judicial crimes perpetrated during the war. While the West German judiciary unshakeably stood and still stands for the principle of judicial immunity, after several years (1962), over 160 judges and prosecutors with Nazi pasts went into voluntary, albeit early, retirement. Regular TV broadcasts from the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem had an even greater impact in Germany. On the rising tide of these West German transformations, the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials commenced in December 1963, at which 20 members of camp staff were indicted. It is worthy of note that during the preparation for the trial, the files of around 800 people were studied, although only the best documented cases were selected. The fact that such a mass trial took place and that a huge body of evidence was gathered, enabling 17 out of 20 defendants to be convicted in December 1965, was by no doubt down to the success of the Central Office of Ludwigsburg and the Attorney General of Hessen, Fritz Bauer. He was the unofficial leader of a group of West German lawyers who understood the need to prosecute Nazi crimes.

Criminals Behind Desks

On the other hand, the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial again exposed the courts’ weakness in bringing Nazism to justice. Contrary to the prosecution’s intentions, the prevailing practice was that of detailed investigation into the individual guilt of the defendants, while the fact that membership of the Auschwitz staff itself made the defendants accomplices to all crimes committed at the camp was ignored. Moreover, the court was very broad in applying the classification of accessory. Under this interpretation, the ‘true’ perpetrators of the crimes were only high-level commanders (e.g. Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heidrich) and those who personally murdered the victims. Thus during the trial, the longest sentences (life imprisonment) were pronounced almost exclusively on lower-ranking personnel and prisoner functionaries (Kapos), while SS officers whose duties included carrying out the selection process on arrival of the transports, thereby sending thousands of victims to their deaths in the gas chambers, were sentenced to several years in prison. Moreover, the court in Frankfurt could not prevent the scandalous behaviour of lawyers, a great many of whom were former Nazis. While acting for the defence, they did not hesitate to mentally torture and insult the former Auschwitz prisoners who had decided to serve as witnesses for the prosecution.

As can be seen, progress in prosecuting Nazi crimes in West Germany after the establishment of the Central Office in Ludwigsburg did not mean at all that those opposed to bringing Nazi criminals to justice gave up. On the contrary, they still enjoyed the support of the majority of the population and also had some major successes. The most important of these was the West German Parliament’s effortless enactment in 1960 of a statute of limitations on all Nazi crimes except murder. From this point, no-one could be prosecuted for the use of torture, medical experiments, theft of fine art or, for example, the destruction of Warsaw. Besides, the acquittal of judge Hans-Joachim Rehse in 1968 emerged as an important precedent. Next to Roland Freisler, he was the most active member of the notorious People’s Court, which during the war sentenced many, including German opposition activists, to death. Thus in practice, the door had been closed to prosecuting former members of the Nazi justice system, even those guilty of the most drastic judicial crimes. In that same year, under circumstances that still remain unclear, ‘someone’ from the Federal Ministry of Justice, unnoticed by legislators, added an article that again broadened the interpretation of ‘accessory’ to the text of an act that had nothing to do with the prosecution of Nazi crimes. From then on, West German courts definitively lost the ability to convict a very important, although specific category of ‘criminals behind desks’.

No Statute of Limitations

Another battle over the prosecution of Nazi crimes centred on the statute of limitations for qualified murders committed during the Nazi era. This took place as early as in 1965, precisely on the 20th anniversary of the end of Second World War. Shortly before that date and following a heated debate, the West German Parliament decided to extend the statute of limitations until the end of 1969. In 1969, a decision to extent the statute further turned out to be easier than before, since a year earlier, following a proposal by Poland, the United Nations General Assembly had adopted the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity. For this reason, the statute of limitations on crimes which led to a sentence of life imprisonment was extended from 20 to 30 years, i.e. until the end of 1979. Only then did the parliament pass an act on non-applicability of the statute of limitations for qualified murder. Importantly, during the debates held in 1965 and 1969, public opinion surveys showed that the majority of West German society opted for statutes of limitations. These proportions did not change until 1979.

According to observers, a change in Germans public attitudes was possible due to the last great trial of Nazi murderers, that of the staff of the Majdanek concentration camp, alongside the American TV series The Holocaust (January 1979). While there is no ambiguity as to the psychological impact of TV images, which for the first time clearly showed the persecution and extermination of Jews from the perspective of a particular family, the way in which the trial of Majdanek personnel influenced German public opinion requires an explanation. The trial of the 16 camp personnel in Düsseldorf in 1975 became a show of excesses to an even greater extent than the Frankfurt trial had been. The public gallery in the courtroom was dominated by neo- Nazis, who demonstrated their hostility towards the prosecutors and witnesses. The defence again exerted brutal psychological pressure on former prisoners. After the above series had been broadcast and had so moved public opinion, times had changed when in 1979 the court released four defendants due to the fact that the witnesses who were due to testify against them had died during the trial. The alleged helplessness of the court and the falsely perceived faithfulness to procedures were severely criticised. From then on, the trial was carried out peacefully and with all due solemnity; however, as far as justification and length are concerned, the sentences of 1981 were very similar to those handed down by the Frankfurt court 16 years earlier.

Although the Düsseldorf trial was the last of this magnitude, it was by no means the last of this type. Nazis are still being convicted in Germany. In 2009, a Munich court sentenced former Wehrmacht officer Josef Scheungraber (born 1918) to life in prison for commanding troops who murdered the villagers of Falzano di Cortona in Italy. In May 2011, also in Munich, the widely publicised trial of John Demjanjuk (born 1920), a former guard at Sobibor, resulted in a six-year prison sentence. On that occasion the media used the term ‘the last Nazi trial’. This year, however, the German prosecutor’s office unexpectedly announced that it was preparing to indict several dozen other perpetrators. A trial is being held in Hagen, North Rhine-Westphalia, of a certain Siert Bruins (born 1921 in the Netherlands), charged with participating in the execution by firing squad of Dutch resistance members. Despite the judiciary’s unexpected surge of activity, these actually will be the last trials of Nazi criminals, since in five years’ time none of them will be capable of standing in front of a court. Critics of the German justice system call attention to the advanced age of the defendants and the fact that during the war they were almost exclusively lower-ranking members of organisations involved in war crimes. At the same time, as a general rule their commanders, holding an immeasurably greater responsibility for the crimes, escaped punishment and are no longer alive. Despite these reservations, the fact that war crimes and crimes against humanity are prosecuted, so long as the suspects are physically able to stand in front of a court, is of great significance. It is a unique phenomenon in modern history.

This article was originally published in a special appendix to Rzeczpospolita daily for the 'Genealogies of Memory' conference on 27 November 2013.