My perception of objects has been shaped by the places and moments in time when they passed through extraordinary experiences. They lost their owners, were plundered, destroyed, confiscated. They were organized, fashioned from nothing, treated as talismans, concealed at the peril of life itself. They were the sole possessions, the entire lineage’s chronicle, all that remained of home, of identity, of memory and hope. No object is merely a thing to me—each tells its own story and speaks of the many human histories in which it is enmeshed.

Since the late 1990s, the humanities have witnessed a movement known as the “turn to things,” and—intensified by years of constructivism and textualism—a longing for the real, for the concrete materiality of existence. “Back to things!” appeals Bruno Latour, the French anthropologist and pioneer of the new humanities. Things have always constituted the object of historical, anthropological, and sociological inquiry, but what is novel is not the subject of study but rather its perspective. Things help us regain contact with reality. The turn toward materiality signifies an appreciation of the synthesizing value of things, their weight as essential interpretive categories, and their role as active creators of social life.

Latour wrote:“For too long, objects have been wrongly portrayed as matters of fact. This is unjust to objects; unjust to science, unjust to objectivity, unjust to experience. Objects are far more interesting, colorful, indeterminate, complicated, elusive, diverse, hazardous, local, material, and networked than the pallid visions with which philosophers have fed us for far too long.”

For Latour, the narrative of things is naturally also a narrative about the owner—the human being—yet one arrives at his/her story “through the thing.” Its role shifts from an episodic decoration to playing one of the principal parts upon history’s stage. From an object wielded by man, the thing becomes his companion on the journey. It shares, and sometimes symbolizes, his/her fate, becoming an extension of the human and co-creating interpersonal bonds.

This can also be told metaphysically.

According to Kabbalah, the world came into being as the consequence of a cosmic catastrophe called the shattering of vessels filled with divine light. The light mingled with the shards of the vessels. This process gave rise to evil. The existence of the world is an unceasing process of repairing the broken vessel, eliminating evil, reuniting what has been sundered. The process of repairing the world is a task given to humanity by God. With the word tikkun, Jewish folk philosophy describes the fulfillment of the destiny of all divine and human creations—that is to say, things. Things are, in our hands, fragments of the world, each marked by our deeds.

Family heirlooms possess a special status, for they are exceptionally precious on account of the love for the hands that cherish them, on account of their association with the fate of those dearest to us. Things must be cherished so they may fulfill their destiny—tenderly nurtured, repaired, entrusted to worthy hands. This is not merely an obligation born of sentiment, but of morality and spiritual mitzvah.

Especially today, in an age of consumerism, ultra-rapid shopping, promotions for disposable items, yet simultaneously in a time of conflicts, wars, and anxieties, it is particularly socially responsible to comprehend the value of things, their history, their identity. Such knowledge will enable us to protect what cannot be replaced by a commercial simulacrum; such knowledge will enable us to discern what we place in the evacuation rucksack, what we preserve, what we entrust to institutions or safe havens. This is our duty as family chroniclers, but also simply as responsible citizens. Family heirlooms are not trinkets from online marketplaces; they are objects capable of preserving our most precious moments and the narratives of who we are. They are fragments of culture, personal and singular things that no one will understand better than we do. Family heirlooms anchor us in reality, in the analog world of life and death, where we can sense what truly matters.

Here is the story of a particular scarf from my book Personal Histories: About People and Things in Wartime. It will best convey what I mean.

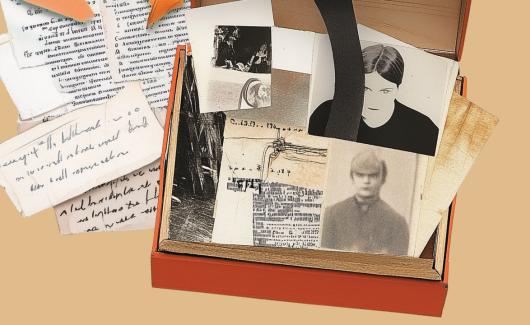

The scarf, adorned with a beautiful nautical pattern, protected a stack of photographs for years. They belonged to Ida, mother of the Israeli artist Mirjam. Mama categorically forbade little Mirjam from looking at them. Only after her death and the death of her husband, in 1996, did her daughter take the bundle into her hands. She quickly put it away again. She did not feel ready to unravel this mystery. Several years later, she thought of it anew. She was then curating the exhibition “Fabrics Remember.” She invited artists to create works inspired by textiles inherited from loved ones. She herself displayed a tablecloth from her grandmother—entirely embroidered with the names of guests who had once sat at grandmother’s table. They would sign the fabric, and grandmother would embroider along the lines. The photographs preserved in the scarf were also like signatures, indecipherable hieroglyphics. She could no longer avoid naming them. The Lohamei HaGetaot Museum in Haifa helped unravel the mystery. She learned that these photographs had been taken by friends from her mother’s home after all its inhabitants had been deported to the camps. They survived the war in hiding. Among the photographs, she found letters her mother had exchanged with family, written in special codes. There were also dates of transports, and finally letters from the Red Cross announcing the deaths of loved ones. Mirjam’s parents managed to escape to Switzerland in time. When her mother learned that no one from the deported family had survived, she collapsed. She was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Grandmother told little Mirjam that mama was ill with typhus.

As an adult, Mirjam calls her creations fiber art. For years she has worked with material, with threads; she crochets, embroiders, knits her pieces. Materials are like people to her—equally sensitive, susceptible to influences, beautifully reciprocating when treated with care. They possess an inevitable expiration date, and none can be replicated.

War enters the homes where we find not only ourselves—the inhabitants—but also our possessions. War reveals that we dwell in fragile containers that disintegrate under the onslaught of violence, and things spill from them like confetti. While our homes remain intact, replete with things and histories, it is well to lend them our ear. We now possess myriad ways of remembering, countless variants for storing objects and histories. Yet simultaneously, we lose patience for quiet listening; we lose sensation in hands touching cold screens. Attending to things can be not only a captivating intellectual and familial adventure but can also bestow upon us restorative, meditative time. No special education is required—it suffices that curiosity, patience, and willingness to enter the labyrinth guide us. Nothing demonstrates better than the stories of family things that grand history always courses through our small lives.

In 2024, on the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Uprising, I co-created an exhibition at the Warsaw Uprising Museum with the fitting title “Real Things.” It comprised 80 objects that narrated what this uprising meant for the city and its inhabitants, its euphoria and its suppression. It is a collection of ordinary objects that became sites of historical inscription 80 years ago—yet their testimony resonates with painful contemporaneity. For several months, through the graciousness of the conservators of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, who invited me to collaborate on the exhibition, I examined objects selected for display. All of them survived because someone determined that these particular ones could not be abandoned in the rubble, in a forsaken home. Someone took them at some moment—during bombardment or after the fall of the uprising, after the war’s end, or while rebuilding the city from post-war ruins.

The museum possesses over a thousand objects in its collection—partly discoveries by museum staff, but largely also gifts from private individuals who performed a gesture of care toward some particular thing, discovered in it a medium of memory, a witness, and decided that they no longer belonged solely to their private sphere but must become public exhibits.

These are things as disparate as: a doll, powder compact, bicycle, bottle, wooden spoon, cup, fork, painting, spectacles, shoes, a dachshund-shaped key chain, letters, cigarettes—yet also remarkably similar, for they are no longer entirely their own, no longer ordinary, but things of a state of emergency—war. Among the objects displayed at the exhibition was also a suitcase—one could scarcely find a more eloquent symbol of wartime fates—you must flee, abandon your life, so you pack only what will fit, what can be carried—literally, but also figuratively. The contents of suitcases are a calculus of reason, intuition, and fear.

The suitcase from the museum is leather, with metal fittings. Katarzyna Pietrusińska- Bojarska carried her possessions in it. Maria Lambasa recalled: “Mama had two suitcases. Tiny suitcases. One was yellow, of pigskin, and the other brown. In the brown one were all the documents, all the mementos, diplomas and so forth. In the pigskin one were three things. There was a tablecloth embroidered by nuns who rescued Jewish children, and there was a little book, my first ever, about the Guardian Angel. There were some photographs from bygone years, and the third thing was mama’s ball gown (…) when they put us in that freight train in Pruszków, it was an open wagon, and we traveled perhaps two days and the rain poured mercilessly, so we held that tablecloth over ourselves, wrung it out, and now every Christmas I spread out that tablecloth.”

Things are also bearers of culture. The fragile walls in which they are housed can collapse all the same, whether they be the walls of an apartment block, a library, or a museum. Family heirlooms are part of profoundly intimate history, yet simultaneously priceless witnesses of time for the entire community. Things are exceedingly particular, yet they are also our universal human language through which we narrate the everyday to one another. They are “anchors” of our memory, which summon images, words—such as Hanna Krall describes them—“hooks” that can be positioned in the appropriate fold of reality, enabling us to hold fast during our life’s ascent.

Of such “anchors” Ewa and Maria told me a story. Both preserve remarkably special family heirlooms—one might say, recovered from traumatic events for blessed memory. Ewa preserves with reverence a bojtel—a camp bag from Ravensbrück, salvaged from pre-war life. Mama embroidered her camp number upon it: 77150. On the bag there still appeared the name of Ewa’s sister, who had carried it to school. Two worlds colliding on a scrap of cloth. The camp registry was not preserved; Ewa discarded the triangles because they reminded her of suffering she wished not to revisit for many years. But she kept the bag. It was pre-war, embroidered by mama; she could not bring herself to part with it. Though only a single number is embroidered there, through it she remembered all the women in the family, for when prisoners were numbered, they stood one behind another. Flattened upon a napkin, on the table, it was indeed the size of a shoe bag. The upper portion whiter, the lower more reddish, but above all gray-brown. The embroidery thread of the name retained a distinct blue hue, but the once sky-blue camp number had grayed. It must have been thread of inferior quality. I noticed upon the material traces of mending and tiny copper-colored stains. A family memento, evidence of atrocity, a school bag, a trace of mama, of sister, relic, testament to survival.

Maria also possesses a memento recovered from a traumatic experience. At a certain moment in our acquaintance, she placed a small bundle before me. Inside was a black-and-red sweater. It emerged that when she departed the Stutthof camp, she assembled herself a “trousseau” for new life—she took whatever might prove useful, for she possessed nothing. Many things were destroyed, but not the sweater. In the sweater from the Effektenkammer, Maria attended high school, and then she carefully folded it and secreted it in the wardrobe. It smells of mothballs. It seems so small to me, as if for a little girl. It has not even worn thin. Affixed to it is a yellowed Post-it note inscribed “Memento from Stutthof.”

In the final section of my 2023 exhibition about women in the Warsaw Uprising, “The Journey of Heroines: Women’s Uprising,” there were no mementos from the war or from times profoundly marked by grand history. I wished for visitors who could examine various aspects of quotidian life—fighting, enduring—of women during the Second World War to be able to experience and comprehend that their lives, those who survived, did not conclude with the Uprising but had in truth only just begun. I wished for them to be remembered not solely as soldiers, scouts, nurses, officers—but also as private individuals who possessed their own preferences, chose engaging professions, accumulated objects that speak not of war but of the good lives they managed to construct.

Together with the exhibition designers, we called this chamber “grandmother’s room”— there was furniture from the PRL era, a sofa, table, armchairs. One could sit and watch video conversations with Uprising participants about their lives—beyond the Uprising, observe how they live, what they cherish. In this section also appeared their beloved objects, their mementos, as displayed artifacts—a treasured shawl, stuffed companion, figurine, commemorative photograph. One cannot grasp the magnitude of effort, courage, hope, and losses bound up with great historical events that tear us from the everyday unless we understand what constitutes our ordinary existence. And likewise, after learning of this grand history, this struggle for survival, without such a postscript, we shall not sense what makes life worth living. These family heirlooms of my heroines, my “grandmothers,” gave me hope that every era possesses things that witness tragedy, but also things that witness miracles. Both varieties of mementos are equally vital—they speak of the full spectrum of humanity.

What we can do is shield them from the refuse heap—of history and of our attention. They will reciprocate with a story. And as the writer Joan Didion observed—we tell ourselves stories in order to live.