He was one of the most widely read and prominent Polish post-war writers. He imbued everyday banalities with existential content, while his uncompromising attitude, especially against communism, resonated with readers globally. The combination of Hollywood charisma, deep literary insight and fearless opposition to oppressive regimes keeps Marek Hłasko’s legacy alive.

Enfant terrible

Born on 14 January 1934 in Warsaw, Marek Hłasko was the only child of

Maciej Hłasko and Maria Łucja, née Rosiak. He was not an easy child. A family legend has it that during the

two-year-old Marek’s baptism ceremony when asked if he would renounce evil spirits, he answered ‘no’, which was

later cited as the evidence of his strong-willed nature.

Marek Hłasko was just three years old when his parents divorced. After the fall of the Warsaw Uprising, which he

spent in Warsaw, Hłasko lived with his mother in Częstochowa, Chorzów and Białystok, before settling for a longer

period in Wrocław, together with his strict stepfather. He finished primary school there in 1948.

Hłasko was not very obedient and, to make matters worse, he was very immature. He therefore changed schools

frequently, and in 1950, at the age of 16, he was accused of being a demoralising influence on his classmates and

expelled from secondary school. By then he was already reading a lot. He particularly loved Fyodor Dostoyevsky,

William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway.

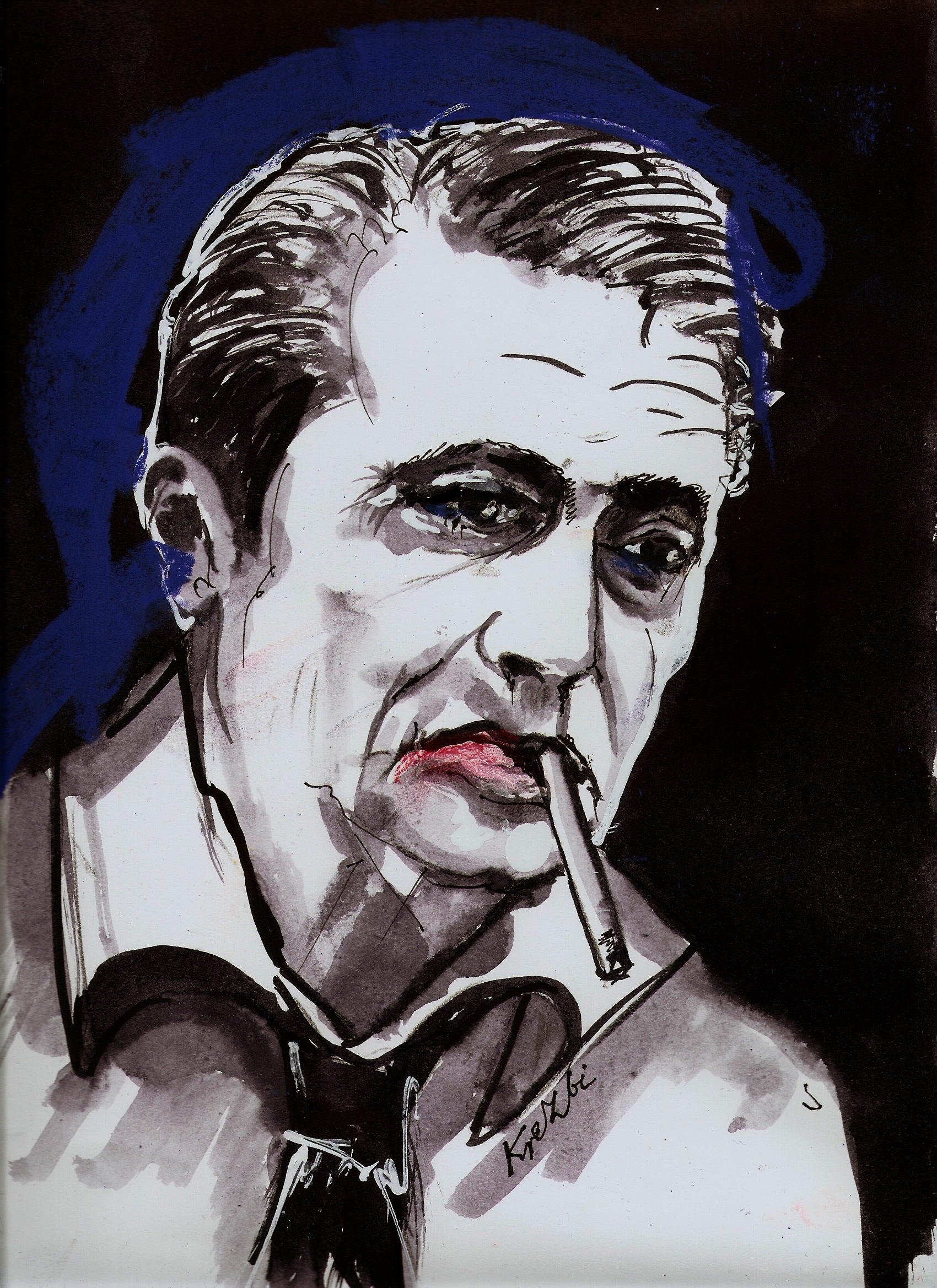

Polish James Dean

At the age of 16, Hłasko embarked on his first employed job. In order to support himself, he obtained his

driving licence and became a driver’s helper and later as a lorry driver, among other things, at the transport depot

in Bystrzyca Kłodzka. His experiences gained there were later a source of inspiration when he wrote his novel

Next-stop Paradise (1959).

He also did short spells of work for the following organisations: the City’s Construction Union, a subway

construction company Metrobudowa, the Transport Association of Warsaw Associations of Consumers and Warsaw Transport

Enterprise of the City Retail Sale. Perhaps he did not stay for long because as a young man he was already making

his first serious attempts at writing.

It was in Częstochowa, while keeping a diary and witnessing the Soviet’s offensive of 1945, Hłasko first

considered a writing career. Years later in Beautiful Twentysomethings (1966), he gave a shocking description of the

march of the Red Army and NKVD troops, the abuses and cruelties of war, an analysis of the Soviet soul and the

mentality of homo sovieticus.

However, he considered the beginning of his career to be in 1951, with the creation of Sokolowska Baza

(‘The Sokolow Base’), his first short story with the vivid characteristics of a stage play. It was also at this time

that he was unexpectedly endowed with the trust of the Party and was appointed to the Tribune of the People

as a field workers’ correspondent. Hłasko’s sharp and witty interventions must have pleased his superiors, for he

was awarded a prize. It was Anatoly Rybakov’s novel The Drivers that supposedly set Hłasko in motion: ‘It was

the first social realist book I had read,’ Hłasko recalled. ‘I have to admit that I fell into a stupor. That’s how

stupid I can be, I said to myself. And I started.’

In 1952, he came into contact with the Association of Polish Writers and Igor Newerly, who was active in the

organisation and acted as a mentor to the young. Hłasko introduced himself as an uneducated chauffeur who tried to

describe his life in his spare time after work. A year later, he was awarded a three-month creative scholarship by

the Polish Writers’ Association, so he eventually left his job as a chauffeur and went to Wrocław.

He became a legendary figure for the younger generation, a symbol of non-conformism. He was well built (84 kg),

essentially oversensitive, insecure and with a tendency to depression, but he was called the Eastern European James

Dean, whom he resembled.

The unsung writer

Writing did not come easily to him at all. He rewrote each page many times, edited and changed every page

repeatedly. He took writing very seriously. For him, it was a desperate attempt to do something with his life, an

escape from the burdens of a simple labourer’s existence. As a writer, he was self-taught. independent, worked hard

and wrote a lot. He published a new book every year.

His manner of writing, as well as the language itself, amazed young people who had never read anything so

uncompromising and free of socialist-realist conformism. It was sincere, without illusions and as true as he knew

how. In the biography written by Hłasko’s cousin Andrzej Czyżewski, it is clear this was influenced by the death of

his father and the occupation, which left a deep mark on the boy, as Hłasko himself later wrote:

‘It is obvious to me that I am a product of a time of war, famine and terror. This

is where the intellectual poverty of my stories comes from; I simply can’t think of a story that doesn’t end in

death, disaster, suicide or imprisonment. There is no posing as a strong man in them, as some people suspect me of.’

Hłasko’s short stories and novels quickly became a thorn in the side of the Party rulers and the socialist press

of the Polish People’s Republic. He was accused not only of promoting drunkenness and moral freedom, but also of a

penchant for nihilism and betrayal of the fatherland. The straw that broke the Party’s bitter spell were the

interviews he gave to the French newspapers Le Figaro and L‘Express. In them, he unequivocally

denounced communism as an inhuman system.

‘In my opinion, the intellectuals I meet here [in the West] react to what is

happening in that [Eastern] world only from the point of view of their own moral attitude, but they do not have this

terrible daily experience. That’s why I feel completely unable to say anything to them ...

If I told them that a worker’s greatest dream is to get drunk for two hours, to

forget himself completely – they wouldn’t believe it. And yet it is true. The misfortune of a man living in a

totalitarian country is the unquenchable feeling of the grotesque and the ridiculousness of himself... the reduction

of dreams... the reduction of desires... the impossibility of reacting to the swine that one sees every day, at

every step of the way.’

[extract from an interview with L’ Express, 1958].

In exile

In February 1958, Hłasko went to Paris on a scholarship, and in October, after being refused a return visa

several times, he decided to stay abroad – in West Berlin. From there he went to Israel. He returned to Europe in

1961. It was then that he began to publish his short stories in the Parisian magazine Kultura (‘Culture’).

His famous autobiography Pretty Twentysomethings – an account of his Warsaw years and life in exile – was

also published there. After its publication, the Polish communist authorities banned the printing of his works in

the country.

He could not live without Poland, but neither could he return to it. His lack of talent for foreign languages

made it hard for him to live abroad. He led an itinerant life, taking on work as a labourer in order to secure basic

living conditions. From 1960 he lived in Germany with his wife, the famous German actress Sonja Ziemann. Although

her role is sometimes demonised in books and articles about Hłasko, it was she who financed their life together and

saved Hłasko when he suffered a nervous breakdown in 1963 and found himself in a psychiatric hospital. Finally, it

was Sonja who, in the last year of the writer’s life, brought him back from the United States, where he had been

working as a salesman in a shop, arranged for his next story to be filmed and gave him the prospect of a tolerable

existence in Europe.

In the spring, the writer travelled briefly to Wiesbaden, Germany, where he died on 14 June 1969, probably from

an overdose of sleeping pills. His ashes were brought to Poland in 1975 and laid to rest in Warsaw’s Powązki

Cemetery.

A legend still alive

At the end of the 1980s, Marek Hłasko’s time had come. For the first time, all of his works were published in

their entirety, without censorship. Hłasko’s books were even included in mandotary reading lists. Many plays and

films were based on his prose. Wojciech Has filmed The Noose, Aleksander Ford The Eighth Day of the

Week and Czesław Petelski Next-stop Paradise as The Depot of the Dead.

Kira Gałczyńska, in her book How Those Years Were Wrong, captured the enduring relevance of Hłasko’s

characters – flawed, cynical, yet deeply human:

‘Hłasko’s heroes were people each of us had met, avoided at times, feared. But

that did not change the fact that they existed, that they lived. A world of illusions, of unfulfilled love, of

beautiful girls who are cynical and calculating, and of the same kind of boys who treat affection like a game, a

sport, while secretly dreaming of the great love they only know from films or books.’

The drudgery of earning a living – in France, Italy, Switzerland, England, Germany, Israel and the United States

– took its toll on the writer’s health. But it also had a kind of mysterious therapeutic effect, triggering a

defence mechanism that converted into a vigorous and regular creativity. He was constantly searching, chasing

something, tearing something down and bursting with that restless spirit of contrariness, contradiction and

rebellion. And out of all this turmoil and busyness, as if from a Ferris wheel, new stories and novels spilled out

at regular intervals, without a trace of haste or chaos, to be remembered for posterity.