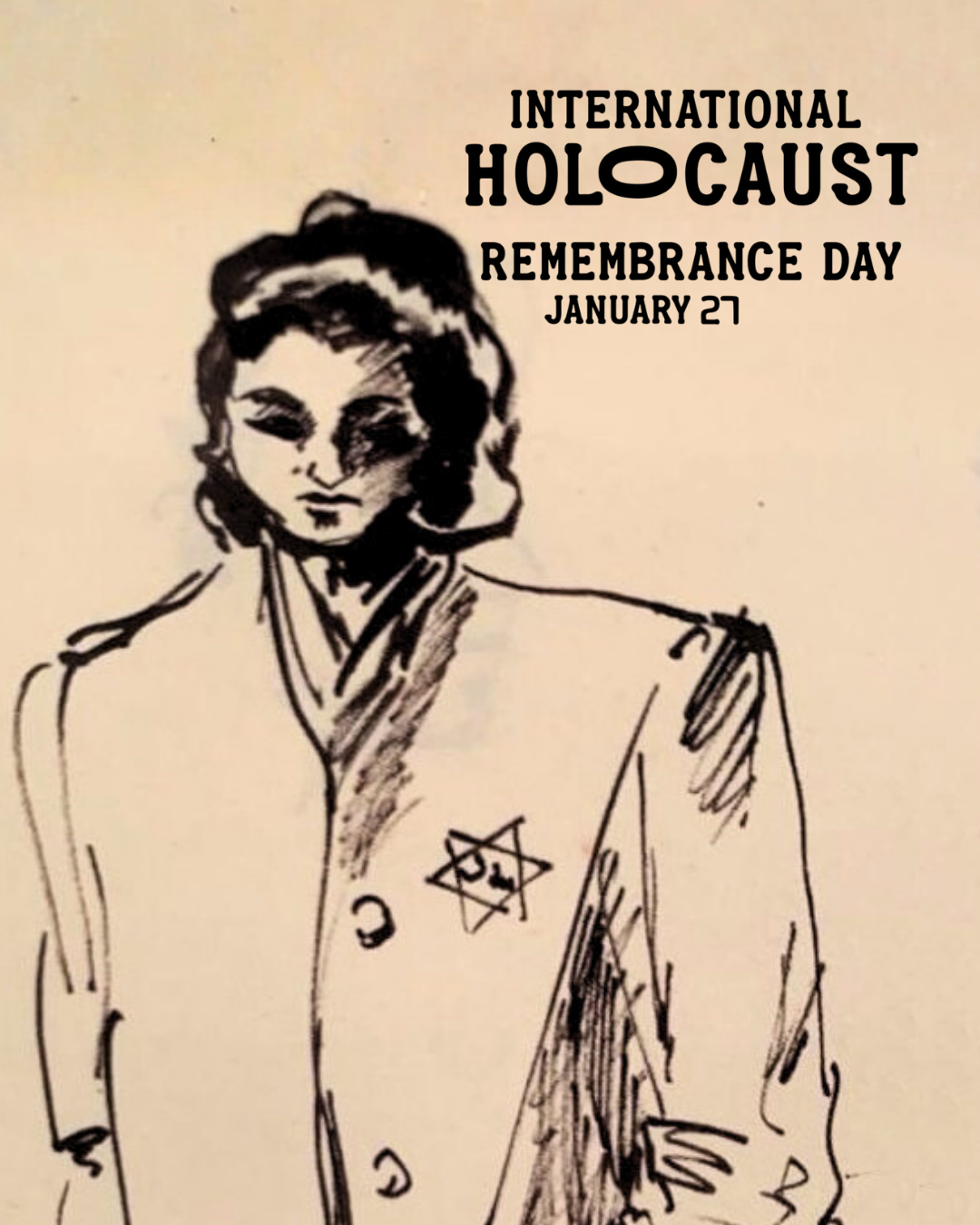

Auschwitz-Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp, Marianne Grant drew for children. Not because the camp allowed innocence, but because the children still needed it — and because drawing could carve out a few minutes in which fear did not occupy the entire room. A line, a colour, a familiar figure on a wall: small gestures against a system built to erase personhood.

Years later, Grant would describe the purpose of these gestures with disarming simplicity: her art saved her life. It saved it in ways both practical and cruelly paradoxical — as a means of exchange, as a shield, and at times as a skill exploited by perpetrators. What began as survival, however, became something else: a form of witness created not after the Holocaust, but within it. Her drawings do not recall the camp from a distance; they carry its presence.

Before survival: becoming an artist

Art did not enter Marianne Grant’s life as an accident of circumstance. Long before it became a tool of survival, it was a language she had learned to speak with discipline and intent.

Born in Prague in 1921 as Mariana Hermannová, Marianne grew up in a cultivated, middle-class Jewish family for whom education and cultural life were self-evident values. Her father, Rudolf Hermann, encouraged intellectual curiosity; her mother, Anna, herself a skilled craftswoman, embroidered, drew, and painted. From an early age, Marianne was surrounded by images, textures, and forms — not as luxury, but as part of everyday life. Drawing was not an escape; it was practice.

Her artistic education was formal and demanding. In 1937, she was accepted into the renowned Rotter Studio in Prague, led by Vilém Rotter — a centre of modern graphic design with a strong emphasis on technical precision, observation, and professional discipline. There, Marianne studied graphics, illustration, and design, training her eye and hand long before she could imagine how decisive this training would become. She learned both how to draw, and how to work: methodically, efficiently, and with limited means.

This distinction matters. Grant did not survive because she possessed some ineffable, miraculous “talent”. She survived because she had a skill — a practised craft — that could be recognised, exchanged, and exploited. Her drawings were not spontaneous expressions of emotion; they were the result of years of study, repetition, and refinement. In the camps, this difference would prove crucial.

When German-Nazi racial laws closed off educational and professional paths to Jewish citizens, Marianne’s training was abruptly interrupted. Her plans to study art formally were shattered by the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. Yet even as restrictions tightened, she continued to draw, to teach, and to refine her skills — quietly, persistently, without knowing that these acts of continuity would later form the basis of her survival. Art, in other words, preceded catastrophe. It was not born from trauma; it was carried into it.

Art as protection

In the camps, survival depended not only on physical strength or chance, but on visibility. To be seen in the right way, by the right people, at the right moment could mean the difference between life and death. Marianne Grant learned this quickly — and learned how art could make her visible.

After being deported to Theresienstadt in April 1942, Marianne was assigned to work in agriculture. This was not an arbitrary decision. She had actively sought this placement, having heard that agricultural labour offered better access to food — both for consumption and for barter. Hunger governed every aspect of camp life, and even marginal advantages mattered. Working in the youth garden placed Marianne in a slightly less exposed position within the camp’s rigid hierarchy, while also bringing her into daily contact with adolescent girls under her supervision.

Here, art quietly re-entered her life. Even in the ghetto, Marianne continued to draw, teach, and observe. She sketched in moments stolen from labour, using whatever materials she could acquire or improvise. Drawing was not an act of resistance in any overt sense; it was something more pragmatic. It created usefulness. It created a role.

In Theresienstadt, usefulness meant protection. Marianne became a leader within the youth garden, responsible for girls aged twelve to seventeen. This position afforded her limited authority and, crucially, access to slightly better food rations. Art functioned as a form of currency — not in the romanticised sense of beauty, but in its capacity to be exchanged for survival essentials. A drawing could secure vegetables, bread, or favours that might later be repaid in kind.

Yet art also provided something less tangible but equally vital: recognition. In a system designed to reduce individuals to numbers and replaceable bodies, Marianne’s drawings marked her as someone with a skill, a function, a name attached to an ability. This recognition did not make her safe — no one was safe — but it made her less invisible.

This visibility followed her to Auschwitz-Birkenau German Nazi Concentration Camp, where she was deported in December 1943 together with her mother. Upon arrival, Marianne was assigned to work in the children’s block, caring for children who had been separated from their parents. Once again, art became a means of protection, though now under far more brutal conditions.

Using scraps of paper, charcoal, and improvised tools, Marianne drew with the children, taught them to draw, and painted murals on the walls of the block. These were not grand compositions, but simple, recognisable images: animals, trees, landscapes, figures from fairy tales. Mickey Mouse and Bambi appeared alongside forests and imagined homes. In a space defined by deprivation, these images opened a narrow window onto another world.

Protection here was not only physical. It was psychological, relational, and fleeting. Drawing created moments in which the children were no longer merely inmates, no longer defined solely by fear and separation. For Marianne herself, caring for the children and drawing with them established a fragile sense of purpose. It anchored her to others at a time when isolation could be fatal. Art did not shield her from violence. It did not stop selections, hunger, or disease. But it made her necessary — and in Auschwitz, necessity could delay death.

This protection came at a cost. Marianne’s talent did not go unnoticed by the camp authorities. Her drawings attracted the attention of an SS officer, who commissioned her to create hand-painted storybooks for his children and later demanded a portrait as a gift for his wife. When Marianne fell ill with pleurisy, this same officer intervened, bringing her bread and butter when no medicine was available. His actions likely saved her life. Yet this intervention also exposed her. Through these acts, Marianne’s art brought her to the attention of Josef Mengele. What had protected her would soon be used against others — and against her own sense of moral agency.

Art as relation: children

In the children’s block of Auschwitz-Birkenau, drawing was not a distraction from reality. It was a way of inhabiting it differently — if only for minutes at a time.

Marianne Grant was assigned to work with children who had been torn from their parents upon arrival in the camp. Many of them were too young to understand where they were or why they had been separated; others understood far too well. The children’s block was not a place of safety, but it was distinct from the rest of the camp in one crucial respect: it was a space where a fragile form of care still existed.

Here, Marianne’s art took on a relational dimension. She did not draw for herself alone, nor even primarily for survival. She drew with and for the children, responding to their need for familiarity, reassurance, and structure. Using whatever materials she could find — scraps of paper, charcoal, makeshift pigments — she encouraged them to draw, to recognise shapes, and to imagine scenes beyond the barbed wire.

The images she painted on the walls of the block were deliberately chosen. Disney characters, animals, trees, and landscapes appeared not because they denied the surrounding horror, but because they countered it. These figures were not abstract symbols of hope; they were recognisable elements of a shared childhood culture. Mickey Mouse and Bambi were not metaphors — they were reminders of a world in which children were allowed to be children.

For brief moments, drawing created continuity. It restored a sense of before and after in a place designed to erase both. In this sense, art functioned as a form of resistance that did not announce itself as such. It resisted the logic of total dehumanisation by insisting, quietly and persistently, on relationship.

Marianne was acutely aware of the limits of this protection. She did not believe that drawing could shield the children from deportation or death. But she understood that it could shape how those moments were lived. Her drawings accompanied daily routines in the block — roll calls, meals, waiting. They did not remove fear, but they gave it form, and sometimes distance.

Importantly, these acts of drawing were also acts of mutual recognition. The children were not passive recipients of comfort; they participated, observed, imitated, laughed, and concentrated. Art established a temporary community, grounded not only in shared suffering, but in shared attention.

This relational aspect of Marianne’s art complicates later interpretations that frame camp art solely as documentation or protest. In the children’s block, art was neither. It was care. It was presence. It was the deliberate creation of a space in which the camp’s total claim over the individual was momentarily suspended. Yet even here, art could not escape the structures of power that governed the camp. The very visibility that allowed Marianne to draw with the children also exposed her to scrutiny. The walls she painted were observed not only by the children, but by guards. The space of care existed only insofar as it was tolerated. This tolerance would soon collapse into coercion.

Art under coercion

The same skill that allowed Marianne Grant to draw with children and create moments of fragile care would soon be stripped of its relational meaning and placed at the service of violence. In Auschwitz, art did not remain neutral for long. After her illness and the intervention of an SS officer who provided her with food, Marianne’s work came to the attention of Josef Mengele. From that moment on, drawing was no longer something she could choose to do. It became an order.

Mengele assigned her to produce detailed drawings documenting the bodies of prisoners subjected to his medical experiments — particularly twins and people with dwarfism. She was instructed to draw family trees, physical markings, and anatomical features. Precision was demanded. Emotion was irrelevant. The same disciplined hand trained years earlier in the Rotter Studio was now required to serve a system of pseudo-scientific cruelty.

This was not art as survival through exchange. It was art under coercion — extracted, commanded, instrumentalised. Marianne did not control what she drew, for whom, or to what end. Her drawings were taken from her immediately. She did not know how they would be used, nor whether they would survive. What she knew was that refusal was impossible.

Here, the moral tension embedded in camp art becomes unavoidable. Marianne’s drawing saved her life, but it did so by entangling her in a system that harmed others. There is no clean ethical resolution to this fact. To frame her work for Mengele as collaboration would be a profound misreading; to frame it as resistance would be equally misleading. It was neither. It was coerced labour under threat of death.

What distinguishes Marianne’s experience is not moral purity, but moral clarity. She never romanticised this period. She did not retrospectively justify it, nor did she collapse under guilt. She described it as what it was: something she was forced to do in order to stay alive. Survival did not erase the violence of the act; it coexisted with it.

Even in this context, traces of her earlier relational work remained. Mengele eventually permitted her to paint murals in the children’s block — an extraordinary concession that again reveals the contradictions of the camp system. Art could be tolerated, even encouraged, when it served the regime’s purposes or reduced unrest. That these same murals might also sustain the humanity of prisoners was incidental.

Marianne’s experience under coercion exposes the limits of any attempt to categorise camp art neatly as either resistance or documentation. In Auschwitz, art was never free. It existed within a web of power, threat, and survival strategies. The question is not whether art was compromised — it was — but whether compromise erased its meaning. For Marianne Grant, it did not. But it changed it irrevocably.

Art as witness

Marianne Grant did not set out to document the Holocaust. She did not draw with the intention of creating evidence for the future. And yet, this is precisely what her work became.

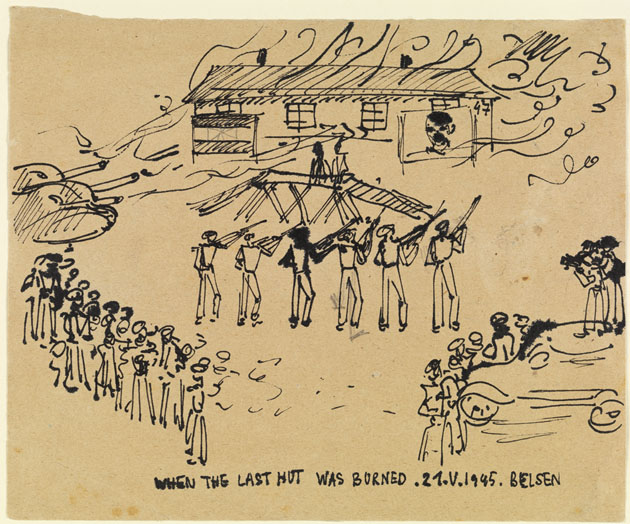

What distinguishes Grant’s drawings from many post-war artistic responses to the Holocaust is not style, but time. Her drawings were not acts of remembrance; they were acts of presence. They were created inside the camps, under their rules, rhythms, and terrors. They do not reconstruct memory — they record experience as it unfolded.

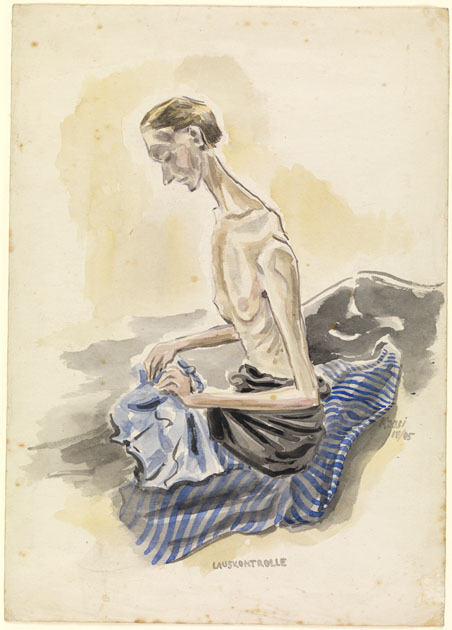

This immediacy gives her work the character of first-hand testimony. Unlike artists who returned to camp imagery years later, Marianne drew what she saw when she saw it, using limited materials and without the possibility of revision. The lines are spare, sometimes hesitant, sometimes abrupt. There is no compositional flourish, no symbolic framing. Bodies appear thin, postures slumped, faces simplified almost to anonymity. What emerges is not expressionism, but observation. This lack of aesthetic distance is precisely where the power of her drawings lies. They do not ask to be admired. They do not dramatize suffering. They insist on attention.

Art historian Jo Meacock has described Grant’s work as occupying a space between survival and witness — not fully conscious of its future function, yet unmistakably bearing it. Marianne herself resisted the idea that she had been “documenting” the camps. She did not see herself as an artist-reporter. Drawing, she maintained, was simply what she did to stay alive.

And yet, intent is not the only measure of testimony. What matters equally is position. Grant’s drawings were produced inside the system of persecution, not from its aftermath. They were not shaped by hindsight or narrative coherence. They record fragments: a queue, a body, a posture, a moment of waiting. In their accumulation, these fragments refuse abstraction.

In this sense, her art challenges the very category of “camp art”. It is neither illustration nor protest, neither private diary nor public accusation. It is closer to a visual statement made under duress — an involuntary archive of the everyday mechanics of dehumanisation.

Crucially, Grant’s drawings do not attempt to explain the camps. They show them. This distinction matters. Explanation risks closure; showing resists it. The drawings leave space for the viewer’s discomfort, refusing to guide interpretation or provide moral resolution. This quality becomes particularly striking when contrasted with the popular expectation that Holocaust art must be sombre, dark, and overtly tragic. Grant’s work does not conform to this expectation — and that refusal is itself significant.

Colour, innocence, refusal of despair

One of the most striking aspects of Marianne Grant’s camp drawings is their use of colour. In a visual culture that has come to associate the Holocaust almost exclusively with greys, blacks, and the stripped-down aesthetics of despair, her work unsettles expectation.

Colour, in Grant’s drawings, is not accidental. Nor is it decorative. It appears where it seems least appropriate — in the children’s block, on the walls of barracks, in scenes of imagined nature. Flowers bloom, animals move, familiar cartoon figures smile. At first glance, these images may appear incongruous, even naïve. Look closer, and their function becomes clear. Colour was not a denial of reality. It was a refusal to allow reality to define the entirety of human experience.

Grant did not use colour to soften the camps or make them bearable in retrospect. She used it in the moment, as a deliberate counterweight to a system designed to drain life of meaning. In spaces where everything was regulated, rationed, and stripped of individuality, colour reintroduced choice. It asserted that not everything could be dictated by the logic of the camp.

The presence of Disney characters and fairy-tale imagery has often puzzled later viewers. How, one might ask, could such motifs coexist with mass murder? But this question misunderstands their purpose. These images were not attempts to escape the camp through fantasy. They were anchors to a shared cultural memory of childhood — a memory that the camp sought to erase.

For the children who lived in the block, these figures were recognisable, comforting, and relational. They did not transport the children elsewhere; they reminded them of who they were before arrival. In doing so, the drawings resisted the camp’s central aim: to transform people into interchangeable, dehumanised units. Grant herself was acutely aware of the fragility of this resistance. She did not believe that colour or drawing could undo terror. What they could do, however, was preserve a narrow space of inner life — a space not fully accessible to violence.

This insistence on inner life marks a crucial ethical stance. Grant did not aestheticise suffering. She did not draw scenes of brutality for their own sake. Instead, she chose to depict what the system tried hardest to annihilate: ordinary gestures, moments of care, traces of imagination. In doing so, she rejected the idea that horror alone should define representation.

Her use of colour also complicates later expectations placed on Holocaust testimony. Viewers often demand that such testimony conform to a specific emotional register — solemn, sombre, unrelievedly dark. Grant’s work refuses this demand. It insists that despair was not the only emotional reality of the camps, and that acknowledging moments of light does not diminish suffering. On the contrary, it reveals what was at stake.

Silence after survival

Survival did not lead immediately to testimony. For Marianne Grant, it led first to silence. After liberation, she and her mother were evacuated to Sweden to recover from illness and exhaustion. There, Marianne slowly returned to physical health, learned to live without constant fear, and began to imagine a future not defined by the camp. Soon after, she moved to Scotland, married, raised a family, and resumed her artistic education at the Glasgow School of Art. From the outside, her life followed a trajectory of rebuilding and stability.

Her drawings, however, did not follow her into public life. For decades, the works she had created during the war remained stored in a trunk in her home. She did not exhibit them. She did not speak publicly about her experiences. Even her children grew up knowing little about what she had endured. This silence was not imposed; it was chosen.

Grant never described this period as repression or denial. Rather, it was a way of living forward. She did not see herself as a witness-in-waiting, nor did she feel an obligation to narrate her past for others. The drawings had served their purpose once already. They had helped her survive. She did not yet need them to speak.

This long silence complicates common assumptions about Holocaust testimony. We often imagine survivors as either compelled to speak immediately or traumatically unable to do so. Grant’s experience suggests a third possibility: testimony postponed, not out of fear, but out of a desire for ordinary life. Silence, in this sense, was not absence. It was containment.

The drawings waited. They existed, intact but dormant, carrying meanings that had not yet been activated. Their potential as testimony depended not only on the act of creation, but on the moment of reception. That moment would come much later, when Grant herself felt ready to relinquish private ownership of her past. This delay is ethically significant. It reminds us that testimony is not an automatic consequence of survival. It is a decision — one shaped by time, context, and the changing demands of memory.

When art returned to the world

When Marianne Grant finally decided to bring her drawings out of the trunk and into the public sphere, it was not because she felt compelled by history to do so. It was because the conditions around memory had changed — and because she herself had changed with them.

The turning point came after the death of her husband. For the first time, Grant found herself alone with a body of work that no longer belonged solely to her private life. The drawings, once tools of survival and then objects of silence, began to demand a different kind of presence. They were no longer only reminders of what she had lived through; they had become documents of a world that was receding into history.

Grant’s decision to exhibit her work was deliberate and measured. She did not seek recognition as an artist in the conventional sense, nor did she frame her drawings as masterpieces. Instead, she presented them as what they were: visual records created under conditions that defied comprehension. In 1997, she was invited to recreate her mural from the children’s block of Auschwitz for Yad Vashem’s exhibition “No Child’s Play”. The act of recreation was itself significant. It was not an attempt to reproduce trauma, but to translate memory into a form that could be shared responsibly.

Exhibitions followed in Scotland, most notably at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. For many viewers, these drawings were their first encounter with camp art created not after the war, but within it — and created by a woman who had chosen, for decades, not to speak. The impact was profound precisely because the works resisted spectacle. They did not overwhelm; they invited sustained attention.

As Grant began to speak publicly, she did so without bitterness or accusation. She did not frame her story as a moral indictment, nor did she claim authority through suffering alone. Instead, she spoke with restraint, clarity, and an unwavering commitment to human dignity. Her testimony was not about vengeance, but about responsibility.

Education became a central aspect of this renewed public role. Grant worked closely with schools, educators, and museums, engaging directly with young people. She understood that as the generation of survivors diminished, the burden of memory would shift. Her drawings were not meant to shock students into awareness; they were meant to teach them how to look, how to ask questions, and how to recognise the early signs of dehumanisation.

In this phase of her life, art assumed yet another function. It was no longer protection, relation, or survival. It became mediation — a bridge between lived experience and historical understanding. Grant did not insist on how her work should be interpreted. She trusted viewers to meet it with seriousness. What returned to the world was not only a body of drawings, but a mode of witnessing grounded in humility. Grant did not speak because she had to. She spoke because she chose to — and because she recognised that silence, once protective, could no longer carry the weight of the future.

Marianne’s legacy: responsibility after witnesses

Marianne Grant never claimed ownership over Holocaust memory. She resisted the idea that her experience granted her moral authority over others. Yet in the final decades of her life, she became acutely aware that memory does not survive on its own — and that when witnesses disappear, responsibility does not vanish with them. It shifts.

Grant’s legacy is not defined solely by what she endured or what she drew, but by how she understood the future of remembrance. She observed with concern the growing distance between historical events and contemporary consciousness, especially among younger generations for whom the Holocaust risked becoming an abstract chapter rather than a human catastrophe. Denial, distortion, and trivialisation were not theoretical dangers; they were already present.

In this context, her drawings assumed renewed urgency. They did not compete with photographs or archival documents. Instead, they offered something different: a human-scale entry point into history. Created without the intention of educating future audiences, they nevertheless proved uniquely suited to that task. Their simplicity resisted sensationalism. Their restraint demanded attention. They asked viewers not only to learn, but to reckon.

Grant believed deeply in education — not as the transmission of facts alone, but as the cultivation of ethical awareness. She worked with schools and educational initiatives that emphasised critical thinking, empathy, and historical responsibility. Her participation in programmes such as Vision Schools Scotland reflected her conviction that Holocaust education must extend beyond commemoration into the present, addressing prejudice, exclusion, and the early warning signs of dehumanisation.

Crucially, Grant did not frame memory as inheritance alone. She spoke instead of stewardship. Memory, in her view, was not something received passively from the past, but something actively maintained — or lost — through everyday choices. This belief shaped how her family engaged with her work. Her children and grandchildren did not become custodians of a fixed narrative, but guardians of a fragile legacy that required care, interpretation, and renewal.

This understanding resonates powerfully today, as the last survivors pass away. The absence of living witnesses does not absolve societies of responsibility; it intensifies it. Without direct testimony, remembrance must rely on materials, narratives, and ethical commitments shaped by those who remain.

Marianne Grant’s art does not offer answers to this challenge. It offers a framework. It shows how art can function without grandiosity — how it can preserve dignity without simplifying suffering, and how it can bear witness without claiming closure. Her drawings endure not because they are exceptional artworks in a conventional sense, but because they remain honest to the conditions under which they were created. They do not ask to be admired. They ask to be read.

In the end, Marianne Grant did not paint to be remembered. She painted to survive. That her art now teaches others how to remember is not a coincidence, nor a triumph. It is a responsibility — one that begins where witnesses end.

***

Editorial note

This article is based on the publication “Painting for My Life: The Holocaust Artworks of Marianne Grant” (2021), by Dr Joanna Meacock, Peter Tuka, Deborah Haase, and contributing authors. The book is one of the most comprehensive studies of Marianne Grant’s life and work, presenting her art as a first-hand visual testimony of the Holocaust and offering crucial insight into the role of artistic practice under conditions of extreme violence.