Lena Sulz

Poland/Germany

During the last school holidays I stayed in Warsaw with my grandmother Basia. We spent long evenings talking about our family—her parents, how she met my grandfather, our ancestors, and countless family stories.

One day we went to Café Nero for Grandma’s favourite coffee, while I sipped a smoothie and ate a warm baguette sandwich. That was when I asked her how she had spent her own childhood: what she did at my age, where she went to school, and the name of her best friend.

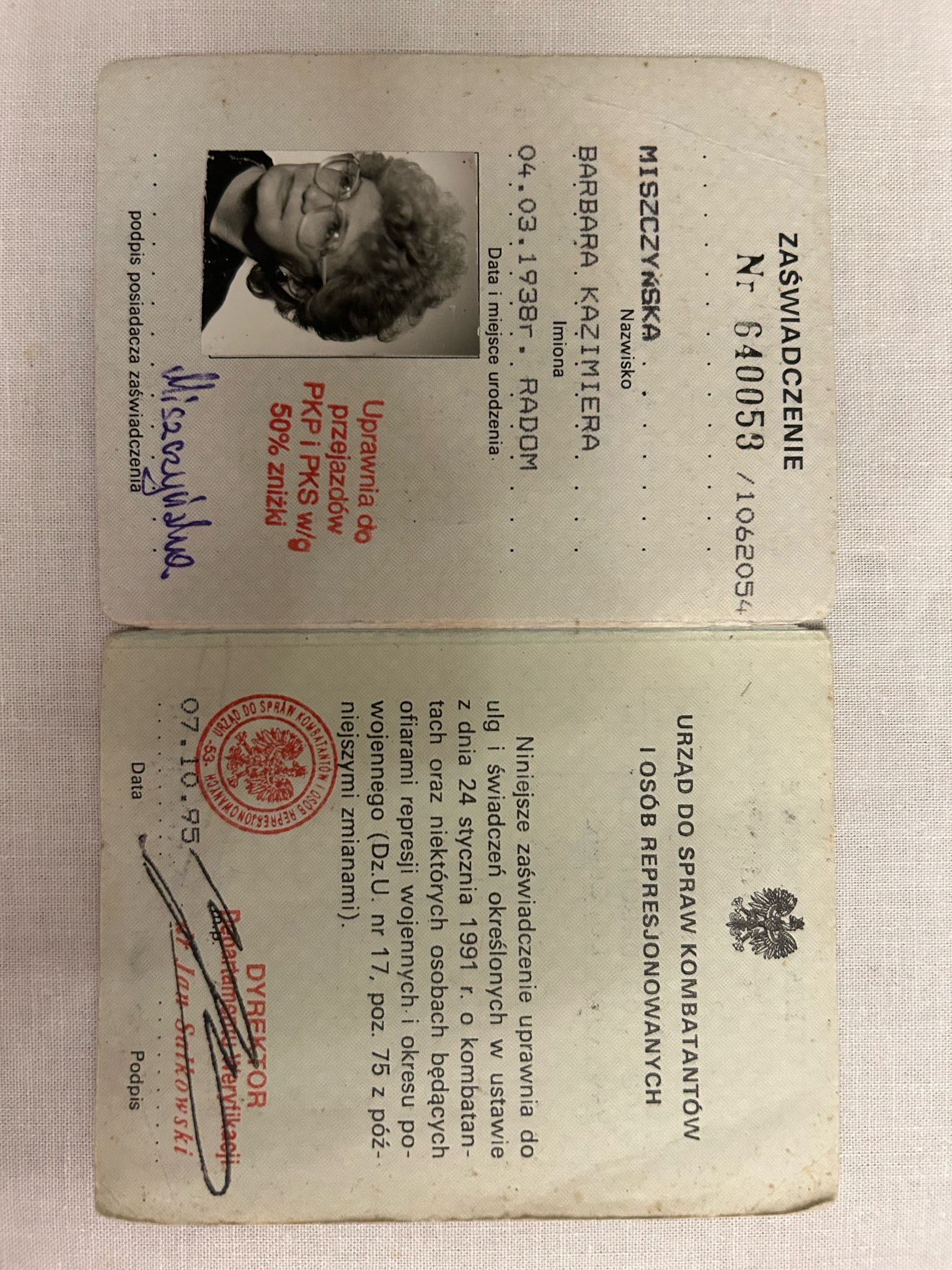

Grandma hesitated to revisit those years, and I did not understand why. Eventually she took a little calendar from her handbag; tucked behind the cover was a small blue booklet, worn and fragile, like an old identity card. She began to talk. Wanting to preserve her memories, I decided to film her with my phone so I could take the recording back to Germany, show it to my older sister Maja and to Dad—and perhaps use it later in Polish history class. Our history teacher once said that if our grandparents are still alive, they could visit the Polish school in Germany and share their childhood stories.

Grandma insisted we should remember the good things; the episode she was about to tell had never been a happy memory for her family, who had tried to forget it. She herself knew the story only from her mother’s account—she had been far too young to remember any of it.

I was hearing it for the first time. Grandma Basia was born in 1938, just before World War II. Her parents were well educated, owned a large house, employed a nanny and a housekeeper, and my great-grandfather Tadeusz Koryciński managed an arms factory in Kraśnik.

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the factory began to evacuate east. On 17 September 1939 the Soviet Union attacked as well, dismantled the plant within days, and deported the workers and their families deep into Russia.

Great-Grandfather Tadeusz, his wife Władysława, their baby daughter (my grandma), and the child’s nanny were transported to Siberia. Tadeusz’s sisters, Alina and Stefania Breyer, missed the train and thus remained in Poland.

Grandma—barely a year old—travelled in a freight wagon thousands of kilometres east. The cars, meant for animals, had no windows, no seats, no heat. Passengers sat on the floor through a journey that lasted weeks, given only an occasional slice of bread and a little water. They finally disembarked in Novosibirsk, some 4,000 km from Warsaw.

The Soviets ordered everyone off the train to fend for themselves. To cross the River Ob, Great-Grandfather built a raft. The family boarded it, but the craft broke apart; Grandma, her mother, and the nanny were swept one way, her father another. The current was strong, and they remained separated for a month before finding one another in an area where Poles were being forced to work.

They were assigned to the collective farm “Krasny Partizan” near Novosibirsk. Great-Grandmother and Great-Grandfather laboured for nothing but a slice of bread and a few carrots.

Grandma recalls that she was always hungry. She and her younger brother Czesław—born in Siberia in 1940—constantly begged their mother for food, saying that the mothers who had stayed in Poland gave their children something to eat. All they had was a weed called goosefoot, boiled into soup. At five she began primary school in Siberia, quickly mastering Russian and becoming a top pupil. Her sister Krystyna was born there in 1943.

The family endured seven years of forced labour and Siberian winters. When the Polish Kościuszko Division formed in the USSR, Great-Grandfather Tadeusz enlisted; military service was the only hope of bringing families home. He fought all the way to Berlin and was awarded the Cross of Grunwald in spring 1946. That year his family returned from Siberia and settled in Końskie, where Great-Grandmother’s parents lived. Two more sons were born after the war—Piotr in 1947 and Aleksander in 1950. Of all the children, only Grandma, Aunt Krystyna, and Uncle Czesław survived the ordeal in distant Siberia.

Grandma came back to Poland malnourished, with health and skin problems caused by hunger, filth, and poverty. When relatives met them at the railway station, the family were so exhausted, dirty, and ragged that no one recognised them. For many years they were forbidden to speak of what had happened. Only when my mother was at school did Grandma receive her Sybirak (Siberian Exile) identity card, and reunions were organised for those who, like her, had been deported.

Grandma’s story moved me deeply. I listened carefully and asked whether she had any keepsakes from that time. I had never heard her speak of it before, nor had I known that my grandmother was a Sybiraczka—a survivor of Siberian exile.