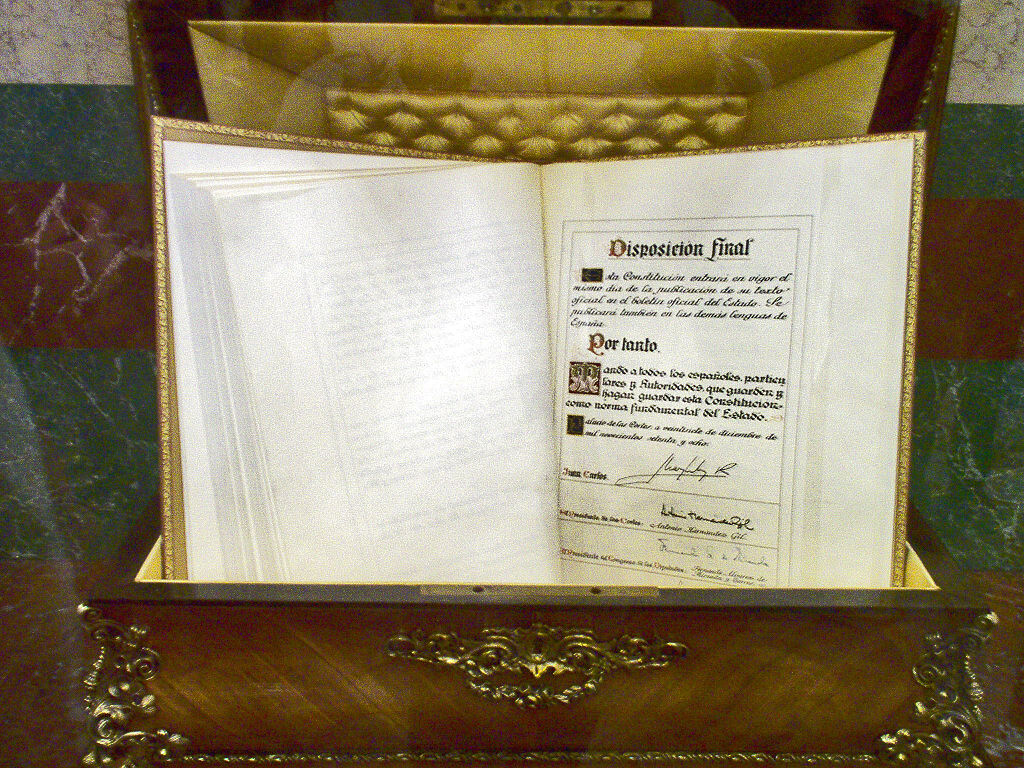

“Good morning democracy”– read the headlines of Spanish newspapers on 7 December 1978[1], as the country ratified a democratic constitution in a referendum the day before, after 40 years of dictatorial rule. Three weeks later, King Juan Carlos I approved the document, making Spain a constitutional monarchy. This marked the culmination of La Transición, the Spanish transition to democracy. But while the changes of the legislative framework might have been concluded, the process of coming to terms with the country’s turbulent past continues up to this day.

La Transición started with the death of the dictator Francisco Franco on 20 November 1975 and the accession of King Juan Carlos I – the grandson of Spain’s most recent monarch – who was designated by Franco as his official successor. The king supported a peaceful transition to democracy within the legal framework of Francoism. All the following political reforms were managed from the inside, by the King as well as other politicians such as Adolfo Suárez González, a former Francoist minister and later the leader of the Union of the Democratic Centre party (Unión de Centro Democrático – UCD) who served as a prime minister first appointed by the monarch and then elected in the general elections.

The political reforms did not abolish the Francoist regime with a break and completely new beginning, but rather gradually transformed relevant institutions and legislations to achieve a democratic system. The changes included introduction of universal suffrage and a two chamber parliamentary system, legalization of political parties and trade unions, as well as the repeal of the Francoist Public Order Court, which used to deal with political crimes.

La Transición was a complex process that was constantly threatened by extremism of the far-right, the far-left and the Nationalist groups. A total of 591 people were killed as a result of political violence between 1975 and 1983[2]. Another proof of how tense the political situation was is the failed military coup of 23 February 1981, when the inauguration of a newly elected government was interrupted and the deputies were held captive for 18 hours.

Taking these circumstances into account, La Transición is rightly portrayed as an extraordinary achievement by the Spanish society. However, one aspect of the democratization process remains a contentious matter – the so-called Pact of Forgetting (Pacto del olvido), an agreement of the Spanish parties from across the political spectrum to avoid dealing with any settlement for past wrongs of the Francoism era. Hence, the Amnesty Law which was promulgated by the Spanish Parliament in 1977. The legislation guaranteed freedom to political prisoners and allowed Spaniards on exile to return to the country, but at the same time assured impunity for those who committed crimes during the Civil War and the Franco dictatorship[3].

The law is still in force and has been used several times to evade investigations or attempts to prosecute those who violated human rights before 1975[4]. Although it has been harshly criticized not only by many Spanish civic and remembrance organizations, but also by the United Nations[5] and Amnesty International[6], either its repeal or any amendments have always been blocked by the extensive majority of the Spanish Parliament[7].

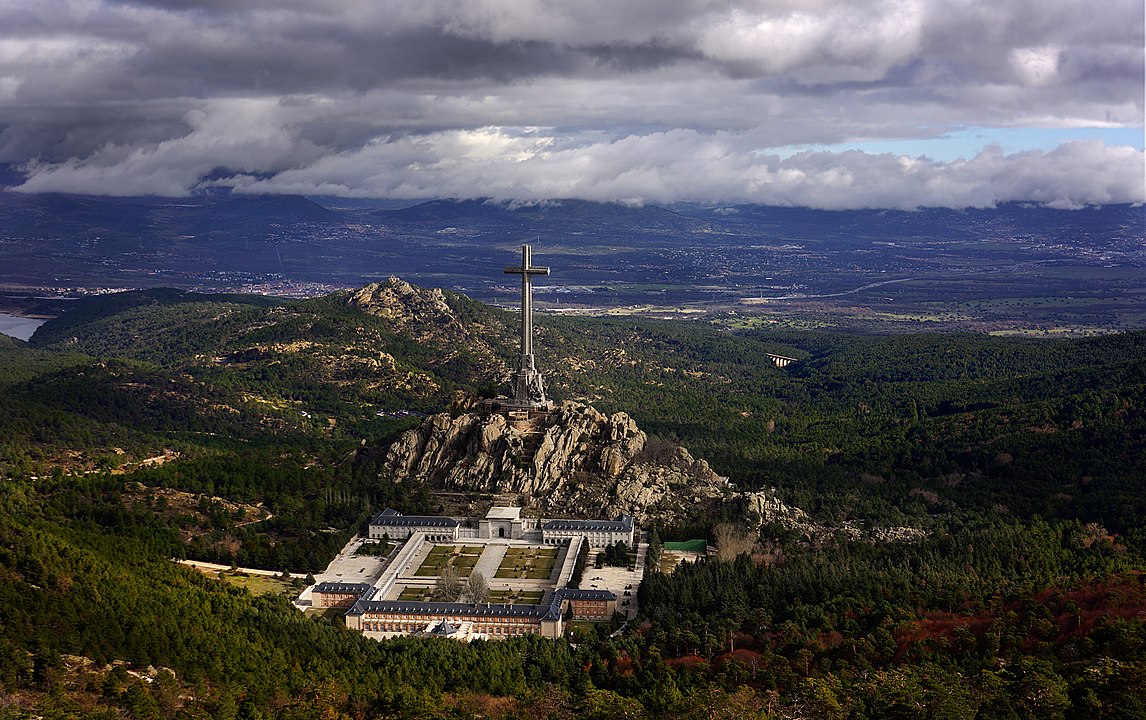

In order to give an alternative to this “forced forgetting”, the Historical Memory Program was passed by the Spanish Parliament under the government of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español – PSOE) in 2007. The legislation was supposed to provide, among others, recognition of the victims of violence on both sides; condemnation of the dictatorship; prohibition of political events at the Valley of the Fallen (El Valle de los caídos – mausoleum where Franco used to be buried); removal of the Francoist symbols from the public sphere; state support in tracing, identification and exhumation of the victims of the repression; improvement of economic compensation and pensions for the victims of the Civil War and Franco regime, as well as grants aimed at the recovery of collective memory and moral recognition of the victims[8].

One of the main goals of the program was to support the exhumation of at least 114 000 victims buried in approx. 2000 Spanish mass graves[9]. However, the budget for the implementation of the legislation was reduced to the point of its suppression under the government of the conservative Popular Party (Partido Popular – PP) in 2013[10]. This constrained the exhumation works to the ones carried out by civil organisations such as the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica – ARMH).

Year 2019, however, did witness what may become a turning point in Spanish historical politics. Nearly four and a half decades after Franco was laid to rest in a monumental mausoleum in the Valley of the Fallen, his body was exhumed and moved to a family cemetery. This came after a heated public debate and months of appeals and legal proceedings, following the decision to rebury the dictator’s remains which was passed by the Parliament in September 2018[11].

The Valley of the Fallen, located about 60km from Madrid, consists of a group of different buildings such as an abbey, a choir school, a hostelry and the cemetery, all of which were built during the dictatorship in order to honour “the Fallen” – the Nationalists who “fell for God and for Spain” (one of the most popular mottos during Francoism). However, after the site had been built it turned out that the families of most Nationalists did not want to have the bodies of their relatives moved there. Relatively few agreed. Instead, to fill the mausoleum up, remains of Republicans were unearthed from mass graves and reburied without their relatives’ knowledge nor consent. This means that for 44 years, Franco lied next to those killed on his order or under his rule. To make matters even more controversial, there is still no information in situ neither about the Civil War nor the dictatorship. Thus, the site can still be interpreted as a place that commemorates and honours the Franco regime – as was its intended purpose – instead of being presented as a multifaceted memory site.

For a long time, reflective remembrance in Spain to some politicians and parts of the society constituted a “nonsense”, as one should not “open wounds from the past”[12]. But 40 years after the La Transición, with a mature democracy in place, the Spanish society seems to start to rethink the choices that have been taken when it comes to memory and reconciliation.

Author: Maria Josepa Cusidó

LIST OF REFERENCES

[1] BBC home: 1978: Spain set to vote for democracy. URL:news.bbc.com

[2] Torrús, Alejandro: La Transición, un cuento de hadas con 591 muertos. Público, 2013. URL:publico.es

[3] RTVE /EFE: La Ley de Amnistía cumple 40 años sin acallar a quienes piden que se derogue o modifique. Radio televisión Española/ Agencia EFE, 2017. URL:rtve.es

[4] Público: La Fiscalía pide suspender las declaraciones de los 19 franquistas apelando otra vez a la ley de Amnistía. Público, 2016.

[5] Reuters: U.N. tells Spain to revoke Franco-era amnesty law. Reuters Agency, 2013. URL: reuters.com

[6] Amnistía International: Ley de Amnistía 1977: Una excusa que dura 40 años, 2017. URL: es.amnesty.org

[7] La Vanguardia/ Europa Press: PP, PSOE y Cs rechazan reformar la ley de Amnistía y dicen que su cambio no serviría para juzgar a franquistas. La Vanguardia/ Europa Press Agency, 2018. URL: lavanguardia.com

[8] Spanish Government Official Site: Memoria histórica. URL: memoriahistorica.gob.es

[9] Spanish Government Official Site: Mapa de fosas. URL:memoriahistorica.gob.es

[10] Baquero, Juan Miguel: Rajoy repite con la Memoria Histórica: cero euros y olvido a las víctimas del franquismo. Eldiario.es, 2018. URL:eldiario.es

[11] Taladrid, Stephania: Franco’s body is exhumed, as Spain struggles to confront the past. Newyorker.com, 2019. URL: newyorker.com

[12] El País/ Agencias: Rajoy: "Abrir heridas del pasado no conduce a nada". El País/ Agencias, 2008. ULR: elpais.com