When you look back at the year 1968, you will encounter the curious fact that while the “Prague Spring” is accorded a great measure of respect and sympathy in the West, in Prague, particularly after the emergence of an independent Czech Republic in the years 1992/93, it is viewed with scepticism and even open rejection by important elements of the new political elite and public opinion-makers. While in Europe, including the former Eastern Bloc, its suppression is viewed as a national, Czechoslovak tragedy, the gist of many Czech commentaries voiced in the first half of the 1990s was that the “Prague Spring” was primarily a struggle between various communist parties, and the whole event is viewed as an episode in the history of an absurd experiment – communism.

In the early 1990s opinions about Dubček varied widely in the Czech Republic. Younger and more conservative journalists located him irretrievably in the communist camp. A more differentiated view conceded that the reformers of 1968 were endeavouring to make the system more humane but at the same time they stood accused of illusory, inconsistent and weak policies. In this more differentiated view, the central importance of the “Prague Spring” lay in its failure, because this finally buried the illusion of the reformability of the communist system. Conversely, such well known protagonists of 1968 as Karel Kosík, Jiří Pelikán or Eduard Goldstücker accuse the new liberal-conservative political establishment of behaving no different towards the “Prague Spring” than the Husák regime at the time. They conclude that the “Prague Spring” was “buried twice” by political rulers, once after 1968 and once after 1989. The neo-liberal parties emerged as the victors of the political process of differentiation which took place in Czechia after 1989 and wanted to make it clear that they had different concepts of democracy and society than those voiced in 1968. With their schematic contrast between a “natural order” and the “hubristic construction” of a technocratically designed, better world, all socialists and moderate leftists were branded as political enemies who imperilled the basic principles of human liberty. The “Prague Spring” became a political issue and the focus of political disputes. Up until 1989 criticisms did not concentrate on party members but on the “generation of 1968” and the dissidents associated with them, for example the civil rights movement “Charta 77”.

If one wants to understand the temporary disdain for the “Prague Spring” after 1989 even within the carefully considered anti-communism of the Czech Republic, then it must understood that a large part of this is due to the particular manner of its failure. Failure was successive and the most difficult part was carried out by the reformers themselves. Their inability not to abandon certain political principles, preferring to relinquish power rather than hoping that their sheer persistence in staying on and occupying certain functions would constitute a lesser evil was not a coincidence. It reflected the basic difference between a reform-communist politics carried out by proconsuls and legal and democratic politics by politicians who know they are bound to the people, to parliament and to their country’s constitution. The suppression of the reform-communist experiment led to resignation, cynicism, and emigration. The twenty years of the Husák regime were characterised by a retreat into private life accompanied by an outward appearance of collaboration with the regime. Repression, but also political conformity and self-abnegation, transformed the country into a cultural waste land. All thoughts of reform were banished from the party until 1989.

The political exploitation surrounding the concept of the “Prague Spring” which characterised the first half of the nineties is only gradually receding. The emergence of more differentiated judgements and a more carefully argued style of altercation in the disputes surrounding the legacy of the “Prague Spring” are unmistakeable. Moreover, despite the controversial assessment of the reformist experiment, the “Prague Spring” and its violent suppression have been deeply inscribed in the collective memory of Czech citizens. According to various surveys, the “Prague Spring” is viewed by the majority as an attempt to renew democracy and as a matter which concerns the majority of the nation.

The perception of the Prague Spring took a different course in Slovakia. Both the reform movement of 1968 and the consequences of its failure were much slower in Slovakia. As the country’s decentralisation turned out to be the only reform of 1968, which survived the political restoration of 1969, this gave the Husák regime a certain legitimacy within Slovakia. Under the communist regime Slovakia experienced the biggest leap in urbanisation and industrialisation in its history. The change of regime in 1989 did not lead to a strong polarisation between a democratic opposition and official structures, and this was reflected in a more muted debate about the communist past and in the rejection of the policy of “lustrations” which was widely applied in Czechia after 1989. In Slovakia after 1989 there was, in general, a more positive attitude to the legacy of the reforms of 1968.

Neither reform communism nor Eurocommunism left a theoretical or institutional legacy on which the newly won democracies after 1989 could or needed to build. Reform communism as a democratic concept is neither identical with the democratic awakening which swept through all levels of society, referred to as the “Prague Spring”, nor with its meaning both for Czech and Slovak history and in European history.

Why did the “Prague Spring” fascinate the West? For socialists and Eurocommunists the “Prague Spring” stood for the hope that the longed for combination of social justice and democracy could become a reality. For modernisers and technocrats it was an experiment which might have shown whether a convergence of systems would be possible, whether the expansion of the welfare state in the West could have had a counterpart in a democratisation with a more market-based economy in the East. For social-democrats the Prague Spring was an inspiration and opened up a perspective whereby the split of the left into communists and social-democrats could have been overcome.

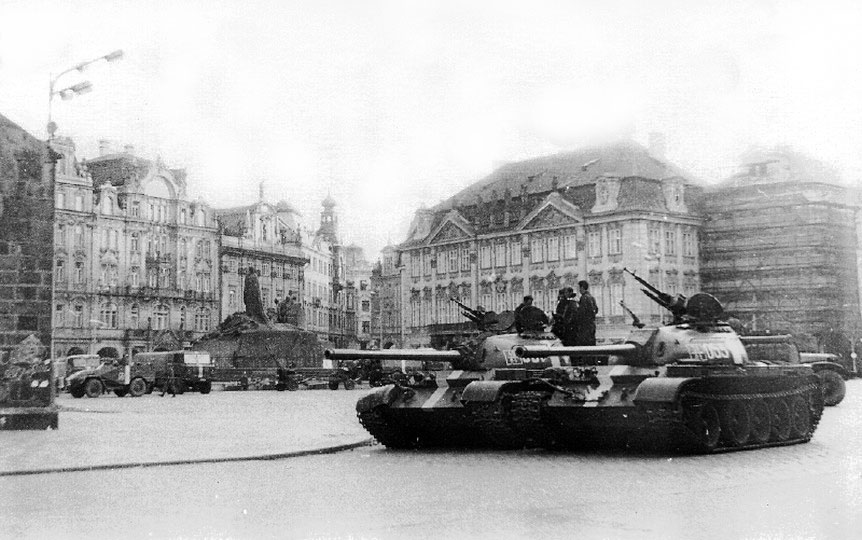

The idea that the totalitarian Soviet communism might be overcome peacefully and without bloodshed electrified even middle-class and conservative politicians such as Margaret Thatcher or George Bush senior. The sheer notion of a non-violent ending of the partition of Europe touched almost everyone, even otherwise apolitical citizens. And finally, the “Prague Spring” was a global media event. Millions of people on their televisions watched the invasion of a small country, which was not threatening anybody but had only set about clearing away its own lies and undemocratic practices. The Prague Spring lastingly changed the view of the nature of Soviet communism. Well-known European intellectuals such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Bertrand Russell denounced the military intervention as “Moscow’s Vietnam”.

In the former Eastern Bloc the Prague Spring has had a lasting impact, as for a few months the mutability of the dictatorial Soviet-style system became a reality in favour of new freedoms. The protests against the military intervention in the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary and the GDR by small and at the time powerless groups of dissidents marked a break in the development of the Eastern bloc. It was the start of a civil society opposition and the historical end of reform communism.

The “Prague Spring” gives little cause for self-righteous judgements. Neither the simple formula of the reform communists who claim that it was a direct precursor of the “Velvet Revolution” nor the neo-liberal explanation which contrasts the interests of the people, who wanted democracy, with those of the reform communists, who were only striving to modernise their rule, are right.

Culturally, the 1960s represented a productive time of new beginnings. The civilisatory backwardness of the East compared to the West was not yet so obvious, and the pre-ecological fetishisation of growth and technology promoted the idea, which many believed in at the time, of a long-term convergence of the systems in East and West. The astonishing global renaissance of Marxism in the 1960s facilitated communication across borders and political blocks. Ideologically, the “Prague Spring” represented the zenith of contemporary misconceptions. The reformers trusted in the idea that the new social structures which had been created by nationalisation could no longer be overturned. Because they really did believe in socialism’s historical mission, they dared to attempt more democracy.

Despite the above mentioned programmatic limitations, the social processes of 1968 represented a system transformation which could not have been halted without resorting to violence. The historical importance of the “Prague Spring lies in the democratic subversiveness of the reform and transformation process which provided historical proof of the potential for a communist dictatorship to be overcome by peaceful means.

translated from German by Helen Schoop

Jan Pauer PhD - historian, translator and philosopher. In 1990-1993 collaborated with the committee of Czech historians set up by the Czech government for studies on history of former Czechoslovakia in 1967-1971. Since 1993 works in Centre of Central and Eastern European Studies of the University of Bremen. Cooperated in realisation of many documentary films, took part in many radio programs and wrote many articles for newspapers on history, culture and politics in Central and Eastern Europe.