The system of "people's democracy" imposed by the communists introduced central authority. One consequence of this was the 6-year plan, which had unfavorable consequences for Wielkopolska. After its completion, the standard of living in Wielkopolska was lower than the average level nationwide. Working conditions worsened - there were shortages in food supply, non-food convenience products and access to accommodation. The citizens of Poznań held traditional values and could not ignore their "socialist reality" –this gave birth to a sense of dissatisfaction and led to protests.

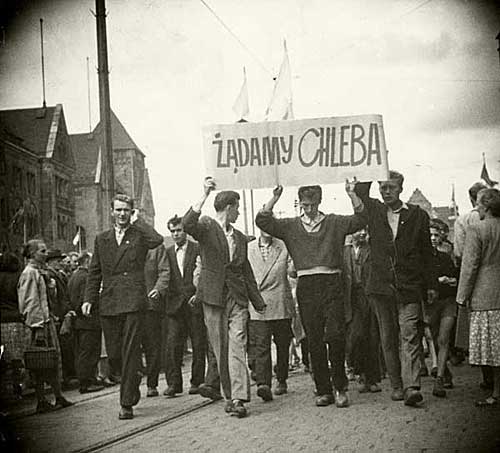

The tipping point came on 27 June, with the Government’s decision to renege on promises to increase wages, return wrongly accrued payroll tax, and change the piecework payroll system that was based on inflated standards – they blamed this about-turn on the deteriorating condition of state finances. It did not take long for the effects of that decision to be seen. The next day, at 6:30 a.m., the crew of the Józef Stalin Plant (formerly the Hipolit Cegielski Plant) in Poznań decided to announce a strike and take to the streets. Alongside workers from other plants, they prepared banners with economic demands ("We demand bread", "We're hungry"), and the crowd moved towards the castle in the center of the city, where the city’s National Council (MRN) had its headquarters.

Gradually, the demonstration, initially of an economic nature, began to escalate into a political uprising - independence, religious, anti-Communist and anti-government slogans were raised. At around 9:00 a.m., the crowd of about a hundred thousand people gathered near the buildings of the MRN and the Regional Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (KW PZPR), demanding that representatives of the authorities come out to the striking crowd. Despite attempts by the local authorities to encourage people to disperse, the protesters stayed on the spot and the slogans transmitted from a radio transmission car, which had been taken over by the strikers, became even more aggressive. They called for the overthrow of the system and for the prisons to be stormed. At around 10 a.m., a group of people broke into the government buildings and the buildings of the Citizens Militia police, where it is likely they got hold of weapons.

Spurred on by rumors about the arrest of workers, the crowd moved to Młyńska street to take the prison located there. Despite the military enforcements sent by the command of the 10th Regiment of Internal Security (KBW), the building was invaded by the demonstrators. All the prisoners were freed and the crowd got hold of more firearms. The crowd, now further encouraged, and armed, decided to occupy the building of the Provincial Office for Public Security. It was then that the shooting started. The head of the office, Lieutenant Colonel Feliks Dwojak, obtained permission to use weapons against the crowd, who were attempting to storm the building. Gunshots were fired between the security officers and a group of about 200 armed demonstrators – this lasted until the afternoon. As a result of this fight, many people were injured. The 13 year old Roman Strzałkowski, who became a symbol of this "Black Thursday", died.

The authorities decided to introduce cadet divisions with armored vehicles to secure the key buildings. These soldiers, who did not have permission to use weapons, became an easy target for the protesters – they pelted them with bottles of petrol and commandeered two tanks. At this point, at about 1p.m., the government forces were given permission to use weapons. As a result, at about 5p.m they managed to secure the building of the Provincial Office for Public Security.

The wave of unrest spread throughout the city. Plundering of buildings, government and also private, began. Several MO police stations were plundered and disarmed. Railway stations were taken over.

In Warsaw, nobody knew what to do next. Only once reports arrived from Poznań, was a delegation with Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz sent. A substantial number of soldiers were also dispatched. At 4p.m., two armored divisions and two infantry divisions - more than 10,000 soldiers - began to enter Poznań.

The suppression of the uprising, which lasted until 30 June, was commanded by Army General and Deputy Defense Minister Stanisław Popławski.

It is thought that 73 people died in the fighting. Hundreds of participants were injured and about 700 people were arrested. Five soldiers from the Polish Army, one soldier from the KBW (Regiment of Internal Security), three officers from the UB (Security Office) and one police officer were also killed.

The Poznań Uprising of June 1956 was the first mass occurrence of the workers rising up against the communist authorities in Poland. The events in Poznań, as well as demonstrating the strength of people's power, also announced the collapse of the idea of Stalinism in Poland. For most sober-minded party activists the necessity for rapid change became evident.

By Andrzej Włusek

Bibliography:

Jerzy Eisler, Polskie miesiące czyli Kryzys(y) w PRL, Warszawa : IPN - KŚZpNP, 2008

Edmund Makowski, Poznański czerwiec 1956 : pierwszy bunt społeczeństwa w PRL, Poznań : Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2001

Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944-1991, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 2011

Ryszard Kaczmarek, Historia Polski 1914-1989, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2010

This article was prepared in cooperation with Historykon.pl. Polish version of the text is available at http://historykon.pl/poznanski-czerwiec-1956-roku/