The creation of Solidarity was a great challenge for the whole political construction of post-Yalta Europe. This construction had been tested on a number of occasions in the post-war decades by the societies striving for freedom from the dependence on the USSR and from its consequence – the communist system.

1. In 1956 - a crisis in Poland and especially in Hungary exposed the hollowness of the strategy of “liberation”; the West remained passive regarding the pursuit of liberty behind the Iron Curtain.

2. In 1968 – liberalisation of the Prague Spring did not cause a significant support from the West and the armed intervention did not disturb the détente process.

3. The politics of easing of relations (détente) meant on the one hand the acceptance of the existing division in Europe, but on the other it could constrain the radical actions of the regimes on our side of the Iron Curtain.

4. Connected with détente but emphasised by Carter (Brzeziński), the politics of defending human rights was an additional restraint and obligation against blatant cynicism.

5. The pontificate of John Paul II from the beginning was boosting both the Poles' and other East European nations' self esteem.

The attitude of the powers regarding the crisis in Poland in the period 1980-81 requires inspection with great detail, however it is already possible to say, that neither the East, nor the West was prepared to revise the status quo. Poland was to remain a part of the Eastern Bloc, the existence of which was no longer questioned. However:

1. The powers of the West emphasised the right of the Poles to govern their affairs without outside interference, in practice – without Soviet intervention.

2. It is difficult to overestimate especially the US initiative from December 1980 warning the USSR against an intervention in Poland.

3. While the rule of non-interference in internal matters of Poland was emphasised, the issues of the need for dialogue among the Poles and the acceptance of “S” as a permanent element of Polish reality were raised.

4. At the same time, in the light of well-known economic problems, the West had no vision or political courage to draft a significant plan of economic aid.

5. We know of no attempts to talk between the Yalta signatories regarding Poland, what would in any case be highly unlikely because of the USSR position.

This listing can be summed up by the probably correct assessment of American politics made by the vice-minister of the People's Republic of Poland, Józef Wiejacz, in early December 1981: “Democratised Poland with recognised political pluralism (although without a free test of strength) remaining a socialist country and a member of the Warsaw Pact is a desirable goal of the USA. Such Poland would radiate its influence on other socialist countries, not excluding the USSR. The influence would be stronger if it was supported by the reform of economy.” Wiejacz added, that the limiting of economic aid for the People's Republic of Poland was the result of uncertainty about further internal political developments in Poland (it was not known who would ultimately benefit from the aid). In early 1981 the Polish government's request for financial aid of 3 billion USD (and additional 5 billion USD from the Western capitals) was rejected. The willingness of the other Western powers to become involved was significantly smaller, e.g. the West Germany government remained restrained in December 1980 and in the Fall of 1981 informed the Polish authorities in Warsaw, that they could not count on such significant financial aid.

Solidarity's leaders and advisors were mainly realists and rightly assessed the limits of possible changes of the status of Poland. They were choosing the politics of “small steps”. Solidarity declared self-limitation and respect of the division of Europe, avoided speaking out on the affairs of other countries and emphasised the will to build the subjectivity of Polish society in a country still controlled by the communists, at least as far as alliances, control of the army and foreign policy go. The tactic of these statements was obvious to everyone. The establishing of a separate course in the contacts with Western leaders, mainly, but not only, trade unions, was a departure from this scheme. During the visits of Solidarity's leaders in Rome, Paris and in the Fall of 1981 in West Germany, the custom of agreeing in the matters of meetings and statements with the Polish diplomatic agencies was disregarded. The “Message to the Working People of Eastern Europe” was a particularly far-reaching departure from the scheme. It was passed by Solidarity's Convention of Delegates in September 1981 and although it was not an effect of political calculation it ultimately played a moral role and made positive relations of Poles with their neighbours easier.

The introducing of martial law on December 13th interrupted the “Polish experiment” and was an attempt do return to status quo ante. The moral commitments undertaken in the era of détente and during the Solidarity period by the Western powers did not allow to return to the politics of cynicism, however. The experience of the attack on Solidarity was an important, perhaps necessary, ingredient accelerating and defining president Reagan's politics towards the USSR. The chilling of the international climate and the intensifying of the arms race in the conditions of technological revolution were challenges, which the USSR could no longer meet.

The Polish crisis, lasting also after 1982, was one of the important factors of the erosion of the post-Yalta system. It was also contributing to the weakening of the Soviet Bloc as a result of the maintained intense resistance and the existence of organised opposition in Poland, which had contact with organizations and even the governments of the Western world.

Solidarity was present in the scope of opinion of the people in the West, the situation which was supported by the press, but also by the enormous humanitarian aid undertaken with the most intensity by Germany. It seems that this aid contributed in a decisive way towards the breaking of distrust between the Poles and the Germans, which was the crucial condition of the success of changes of 1989.

The overcoming of habits and barriers natural in the world of politics required many specific attempts that were for some time very difficult, however. In mid-1985 in a letter to Zbigniew Bujak, being in hiding, Bronisław Geremek wrote: “In international public opinion a view is becoming prevalent that it had to be the way it happened on the 13th of December and that the situation in Poland returned to the East European norm already. And this is the function of the interviews I give: that it could have been different, that <S> does exist, that <S> can be a political partner, that Poland is and will remain different from the others.”

The construction of such an opinion was a result of many factors, including the influence of John Paul II. It seems that his activity should be linked with the breakthrough of 1986, which was the decision of the US government to end the economic sanctions introduced after December 13th depending on the release of political prisoners (including Bujak, arrested in the middle of the year) and making by the Pope the visit of Jaruzelski in Vatican dependant also on the release of the prisoners. The amnesty in September 1986 allowed for open, however still illegal, functioning of the opposition. Jaruzelski was received in Vatican in 1987 and that unlocked the diplomatic contacts of the People's Republic of Poland on the big stage and helped to end the sanctions mentioned earlier. In June 1987 John Paul II could make another visit in Poland, which had a big importance in reviving the activity of Solidarity. Numerous visits of people of importance from the West in Poland in 1987 included from that time the meetings with Wałęsa and his advisors.

The way out of the Polish crisis through negotiations and compromise was in accordance with the ideas and priorities of the Western powers shaped already in 1981. At least until the Fall of 1989 the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc was not taken into consideration, only its pluralisation and evolution. Poland should follow the road of gradual democratic reforms based on a possibly wide consensus. The West was also not ready to tackle the various problems, mainly economic, which had to arise from the rapid dissolution of the Eastern Bloc. This process had to take time.

What had been said earlier leads to the conclusion, that the actions of the leaders of Solidarity in 1989 were rational to the utmost and matched the ideas and expectations of the leaders of the West well and at the same time did not provoke a counterattack of those forces, which would be willing to defend the Soviet empire. The model of Polish transformation became an impulse which stimulated the freedom movements in East Germany and in Czechoslovakia, although not all are willing to admit it today.

The example of a rebellion and self-organization of a society against a monolithic state and its progressing erosion was noticed by other societies. After all, thousands of articles around the world were written about Solidarity, but also about the limited and gradual demands. The peaceful method of protest and pressure became known, together with the building by way of mobilising the masses in a calm, but determined, action. Other movements, such as Sajudis or the democratic movement in East Germany and Czechoslovakia of the end of the 1980s, adopted similar ways of self-organization and protest. Whether it was the example of Solidarity or their own experience can only be answered by further studies and analyses.

Even before the June elections the Solidarity Citizens' Committee passed a statement about international affairs, in which it was written: “We declare readiness to cooperate with all forces working for pluralism and democracy in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, in the USSR. We express sympathy towards the nations of the USSR fighting for their rights, especially the Belarusians, Ukrainians and Lithuanians. […] At the same time we declare that we support that, which strengthens the unity of Europe and the popularisation of the European idea. Poland can not exist without Europe, but there is also no peaceful Europe without Poland.”

The option chosen by Solidarity in 1989 and especially during the forming of the Mazowiecki government and afterwards, was unambiguously pro-Western, aiming to establish equal relationship with the USSR and pave the way to integration with Western Europe. The politics of “small steps”, which was the essence of actions of the mainstream of Solidarity, turned out to be a very effective one, not only for the Poles, but also for the neighbouring nations.

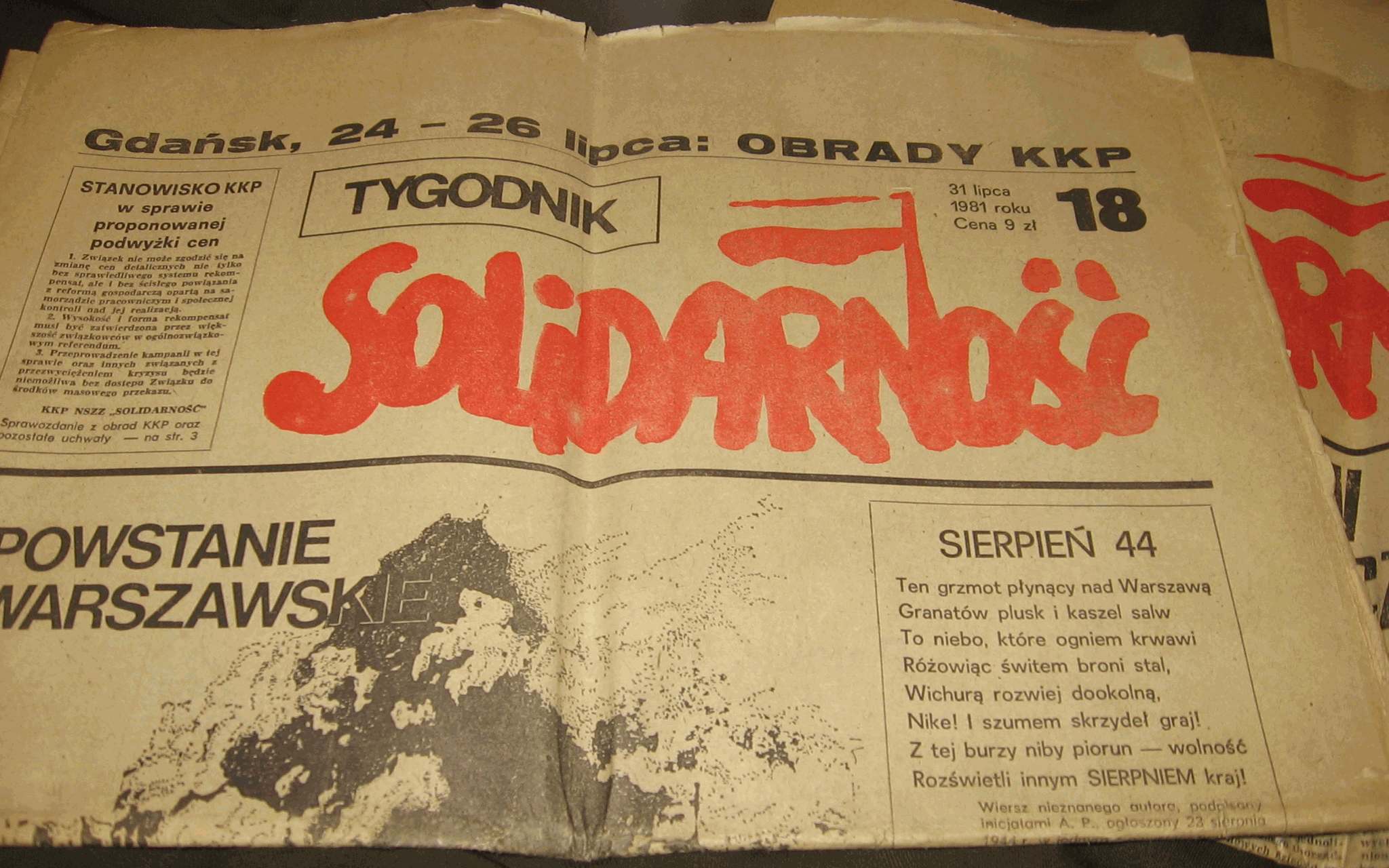

prof. Andrzej Friszke (born in. 1956) – historian, vice-president of Institute of National Remembrance. Linked to the Institute of Political Studies of Polish Academy of Science (PAN). He was editor in Solidarity Weekly „Tygodnik Solidarność”. Member of editor board „Więzi”.