While other Central European countries initiated lustration before Poland did, none consider it an entirely successful process.

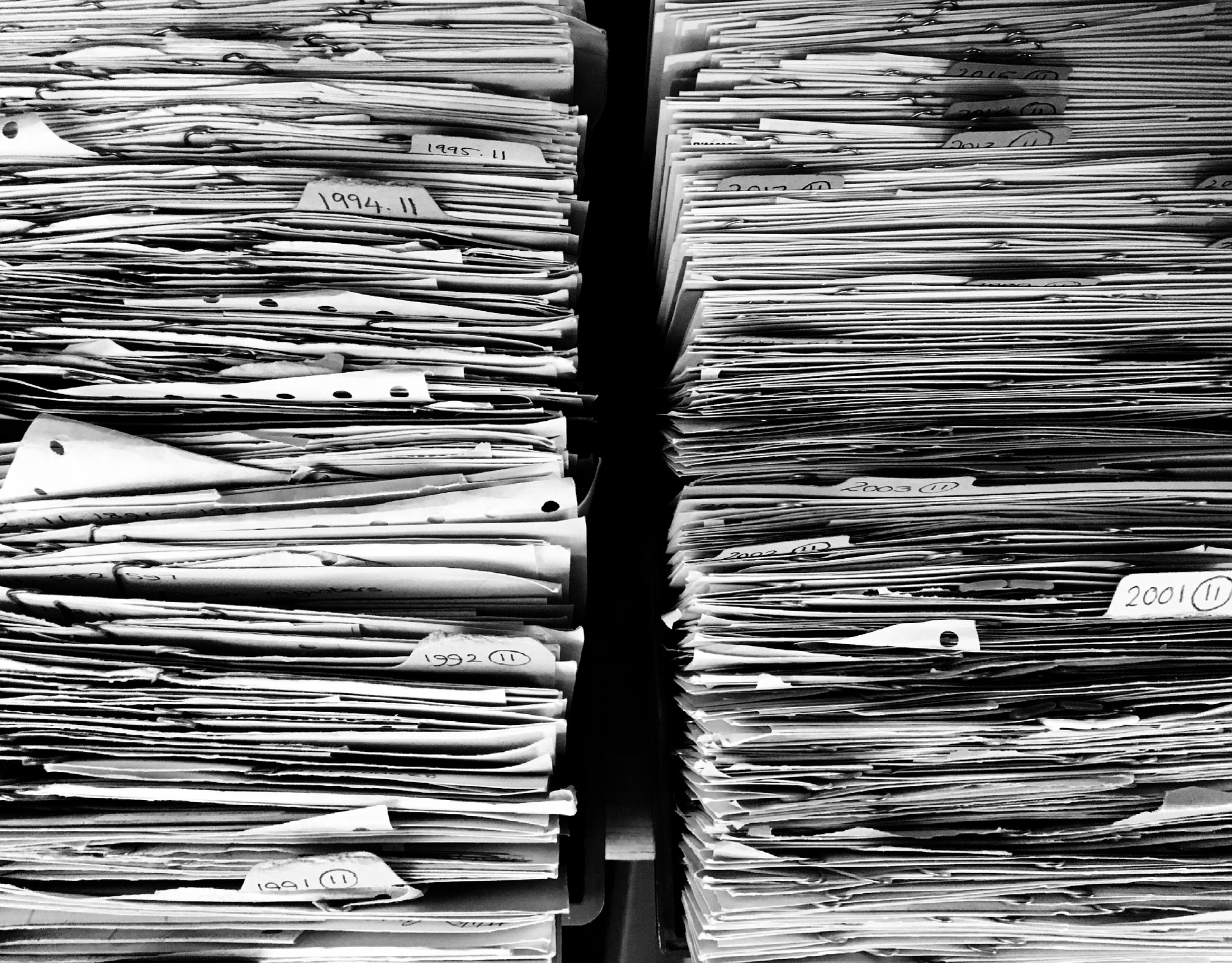

Although more than two decades have passed since the collapse of communism, settling accounts with the old system is anything but complete. This is true regardless of the nature of the revolution: a ‘velvet’ one as in Czechoslovakia, negotiated as in Poland and Hungary or brutal and bloody as in Romania. The lack of complete and credible documentation is the most obvious reason almost everywhere. While the burning of the Polish secret police’s files in Pasikowski’s Pigs is only a movie scene, it is quite close to what actually happened. Developments in the other Soviet bloc countries were no different; just think of the piles of scattered documents filmed by Western journalists in the back yard of the demonstrator-occupied Stasi office in Leipzig.

Dossier game

There was a temptation to use more or less credible documentation against political opponents during the fight for power in post-communist countries, especially in the 1990s. As a consequence, lustration was deprived of its role in dealing with the past and instead created the impression of being a ‘dossier game’ serving the purposes of the powers that be. While in Poland these clashes are symbolised by the ongoing dispute regarding Lech Wałęsa’s past, almost all former Soviet bloc countries have had their share of alleged informers, including the Czechs, who were the first to initiate lustration, and the Germans with their apparently model lustration legislation and the so-called Gauck Office.

Countries, various groups and different institutions have all failed in conducting a complete and consistent lustration process. This includes churches, which the previous system attempted to fight (and infiltrate). Poland’s Catholic Church symbolically completed its lustration at the end of the previous decade but there were no major consequences. Elsewhere, for example in post-Soviet states, no attempts were made to conduct a credible lustration of the local Orthodox Churches. In Bulgaria, it was not until 2011 that the church hierarchy reluctantly agreed to lustration (not surprisingly since, as it soon turned out, the majority of synod members during communism had collaborated with the secret police).

Conducted soon after reunification, lustration in the former GDR was for a long time considered relatively complete. Germany, however, was different because the democratic legislation of West Germany was extended to the former German Democratic Republic, with all the consequences. Established in 1990, the Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Archives, with a staff of 1,600 (referred to as the Gauck Office after the first commissioner) is still very much in demand. Since 1992, two million people have requested access to the files. Initially the office was to continue until 2011, but the German parliament has extended this period by another eight years.

While the office has been relatively successful and has blocked the careers of former Stasi collaborators and agents at federal level, it has failed at state level in the east of the country. As an example, in Brandenburg’s Landtag every fourth left-wing (Die Linke party) MP has had a spell of what could be qualified as collaboration with the Stasi. Past informers have been found in the police and among Western politicians. In addition, some fifty people with a record of working for the secret services are employed at the Office for Stasi Archives and more than 500 work for various federal agencies. More than two decades into the process, some say that complete lustration in a country where every fiftieth citizen has had some contact with the secret political police is in fact impossible. What was Germany’s universally praised lustration process has turned out to be quite superficial, a claim made by Uwe Müller and Grit Hartmann, the authors of the book Vorwärts und Vergessen!.

Agents and confidants

The Czechs were the first among the former Soviet bloc countries to take lustration seriously, screening as early as 1989for StB (Security Service) agents and collaborators. Prior to the first free elections in June 1990, political parties could run checks on their candidates, thus blocking the political careers of many. Czechoslovakia’s new parliament adopted formal lustration laws in October 1991. One applied to all citizens and the other to those serving in uniformed services. If a person was proved to have collaborated with the communist secret police, they were excluded from posts in public administration, public offices, the army, police and state-owned enterprises.

Early on there were legal and interpretational problems. The Constitutional Court ordered a change in some of the clauses. It was found that some people described as ‘candidate’ or ‘confidant’ in secret service documents may not even have known that agents were using them as a source of information. Following their formal adoption, the lustration laws were to stay in effect for five years. However, just as in all the other postcommunist states, this was much too soon and it was clear that more time was needed. The lustration law in the Czech Republic has indefinite duration.

There were scandals involving people from the front pages. Many were prosecuted following the 1992 publication by journalist Petr Cibulka of a list of 220,000 people from the StB archives. Just as with the Polish Wildstein’s list, the problem was that it included former spies and those of interest to the secret police. With no equivalent of Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance, the mistakes were difficult to correct. It was not until 2007 that the Czech Republic established the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (USTRCzR).

The Slovaks took a different approach when they established their own state. From early on, Slovak politicians, especially on the left of the political spectrum, were wary of lustration. The joint Czechoslovakian lustration law expired in 1996 and was not followed up by Vladimir Meciar’s HZDS government. The Nation’s Memory Institute (UPN) was not established until 2002 under a right-wing government. Eventually, it was decided that lustration statements were not mandatory, and even if someone is proved to have had a secret police past, moral stigma aside there will be no legal consequences (e.g. exclusion from public office). Gaining access to UPN archives is relatively easy.

Neither were the Hungarians very enthusiastic about dealing with the past. Despite the militant mood among right-wing groups during the collapse of communism in 1989, Hungarians took a long time to adopt lustration laws. The Alliance of Free Democrats had its proposals, as did the first non-communist government of József Antall. Adopted in 1994, the first act offered a relatively mild treatment of former agents. Not only were secret police collaborators kept safe from any serious sanctions, but also legislators wanted to keep communist security service files secret for as long as 30 years. Due to objections raised by the Constitutional Court, the final version of the law was not ready for another two years, to have finally expired in 2004.

Astonishingly, the governing radically anti-communist Fidesz party is reluctant to address the topic of lustration. Some analysts believe that this is due to the fear of possible blackmail due to intense infiltration of the opposition during the 1970s and 1980s. In a recent bid to revisit the ‘agent’s act’ in June this year, the Hungarian Parliament again failed to pass the bill. This time government coalition MPs abstained.

Secret Collaborator politician

Romania was equally slow with its lustration legislation. With strong post-communist influences, the first governments were in no hurry to deal with the past. It was not until 1996 that the right-wing government of Emil Constantinescu started work on Act 187, a law dealing with Securitate (Ceausescu-era security service) agents and collaborators. Passed three years later, the law turned out to be ineffectual. While data about confidants’ pasts were to be disclosed, there would be no consequences. It was up to voters to decide whether people discredited in the past could hold elected offices. As a result, many a former secret police collaborator is pursuing a political career in Romania. While the agent exposure process gained some impetus after 2006 with pressure from president Traian Basescu, the screening of several hundred people a year compared to several hundred thousand former secret police collaborators does not seem like an effective way of dealing with the past.

As we can see, lustration involving painful consequences for former communist secret service collaborators is merely a demand voiced by former opposition groups. Despite the common belief that the new political elites of Germany and the Czech Republic were most consistent in their lustration policies, the process failed even there. What may come as consolation is that while Polish lustration is criticised for being weak and inconsistent, the majority of the countries in our region have achieved even less in dealing with the shameful past of the communist era.

This article was originally published in a special appendix to Rzeczpospolita daily for the 'Genealogies of Memory' conference on 27 November 2013.