As historical remains, the approx. 3,60m high and 2,6-tons heavy elements of the Berlin Wall are exceptionally linked to the city of Berlin. However, only a few hundred metres out of the 160 kilometre-long barrier still can be found in the German capital. Its longest coherent and preserved section counts as little as 212m. Thus, a question stands: what happened to the rest of the Wall?

It was in the middle of the night of 13 August, 1961 when the lights went out at the Brandenburg Gate in East Berlin. Under the cover of darkness, construction works began on what eventually become a system of walls, fences, barbed wire, guard towers, unused land – a complex which was later to be known as the Berlin Wall or simply ‘The Wall’, as Germans referred to it. The impenetrable barrier divided the city into two parts, becoming a visible sign of the rising tensions between the Western and Eastern Blocs. During the 28 years of its existence, the wall between East and West Berlin cost the lives of at least 136 people who died during their attempts to escape from GDR.

Everything changed in the second half of 1989. The pro-democratic developments in other countries of the former Eastern Bloc such as the Round Table Talks and the following first semi-free elections in Poland, as well as the increasing stream of refugees leaving East Germany via the now opened Hungarian-Austrian border, put the German socialist government under immense pressure. A way to defuse the growing social unrest had to be found. On 9 November 1989, Günter Schabowski, a member of the Socialist Unity Party acting as its unofficial spokesman, announced the new loosened travel regulations during an evening press conference. The event was live broadcasted on radio and TV.

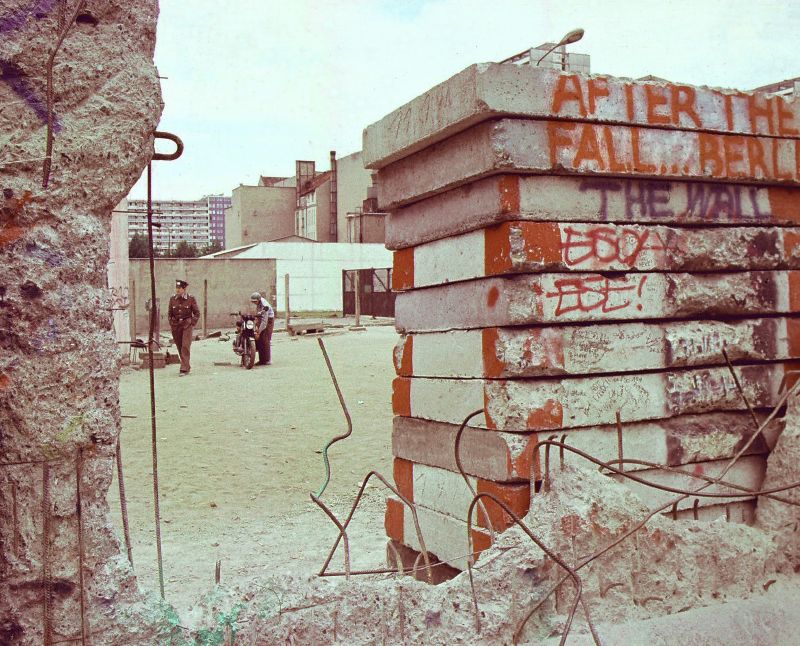

As a result, thousands and thousands of East Germans streamed to the border crossings, pressuring the border troops to immediately implement new directives. The border guards at Bornholmer Straße were first to succumb. The rest, as they say, is history. Pictures and videos of the fall of the Berlin Wall spread around the world: East and West Berliners celebrating on top of the Wall, helping each other reach the other side of the former impervious border, sharing and swinging hammers and chisels to destroy the substance that has separated them beforehand.

Berlin Wall: should it stay or should it go?

At first, tearing down the ‘Wall of Shame’ was considered an act of liberation from the monumental symbol of oppression and the painful segregation imposed by the communist government. The proactive demolition of the Wall by the population and its following official removal organised by the state were based on the consensus that the detested concrete structure in the middle of Berlin needs to be gone as quickly as possible.

Simultaneously, Berliners and visitors to the newly reunited city started to rather vigorously hack out chunks of the Wall in order to acquire a piece of “historical testimony”1. These so-called ‘wall-peckers’ came for diverse reasons. Among them were people hunting for souvenirs, professional merchants who started to sell little bits of the structure within hours after the opening of the border, and those who personally experienced its fall. By taking a piece of the Wall, they obtained a tangible, materialised memory of the revolution that just took place.

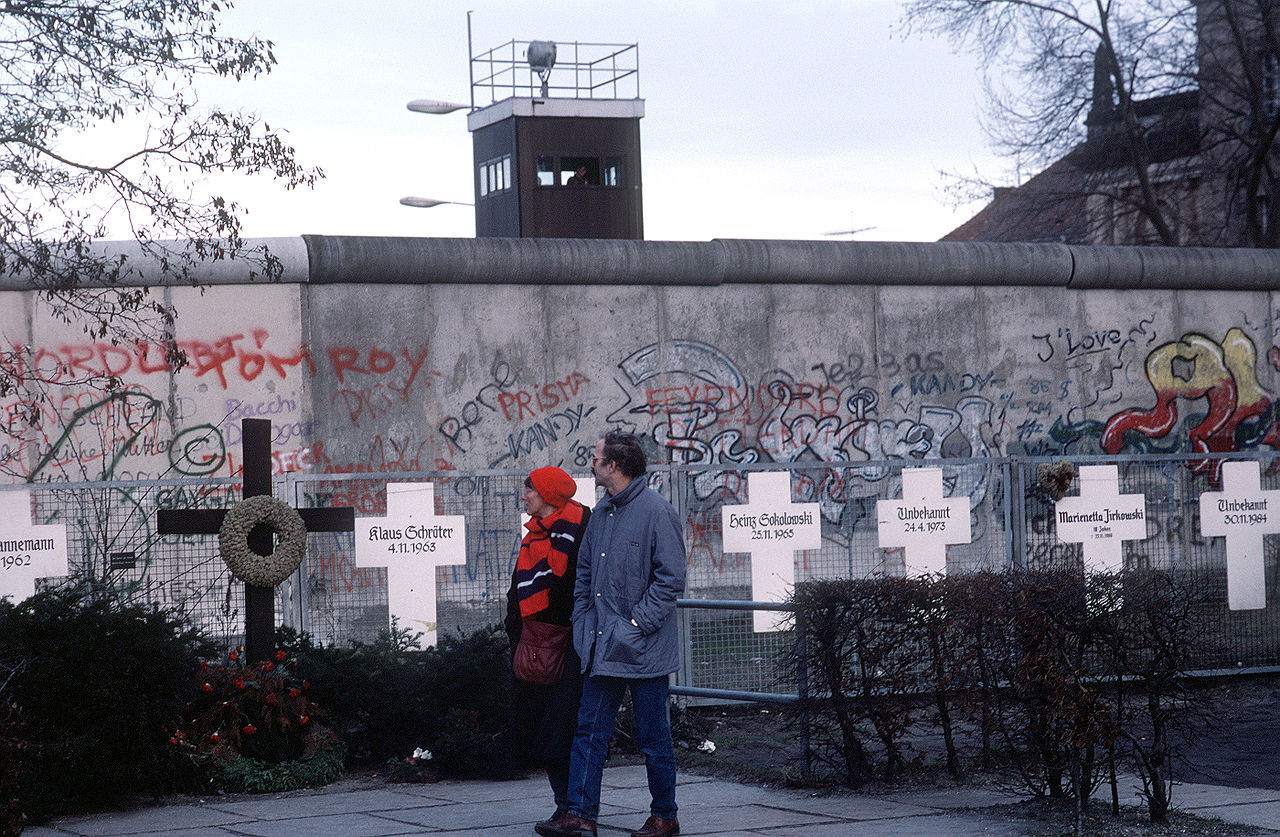

However, as the Berlin Wall was vanishing before everyone’s eyes, the Berlin State Office responsible for its dismantling realised the need for preserving at least some of its parts as the city’s heritage. The strategic decision to put some segments of the barrier under protection was announced on 2 October 1990, exactly one day before German reunification. The resolution was met with criticism: the predominant mood among the public opinion of the time was to get rid of the remnants of divided Germany entirely, once and for all. Only over a decade later, in 2006, the city senate decided to pass a “master plan to preserve the memory of the Berlin Wall”, which led to the opening of the Berlin Wall Memorial and Documentation Centre at the Bernauer Straße three years later. The site, dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Berlin Wall, is now the only place where one can see the sequence of the fortifications preserved in their original state.

Interestingly, letting some remnants of the former border stay did not cause as much controversy – as long as their appearance, and thus: meaning, was first completely changed. The East Side Gallery – a 1,3km long rear wall complex facing former East Berlin converted into an open-air showcase of over 100 artworks – was first opened on 28 September 1990. Having secured an official commission from the GDR Council of Ministers, 118 artists from 21 different countries created murals on the Wall’s still standing segments in which they interpreted its fall2. Their paintings reflected on the oppressiveness of GDR as well as other authoritarian and totalitarian countries around the world, while praising the ideals of democracy and liberty. Applying colourful pieces of art where it used to be prohibited constituted in itself the best proof of the regained freedom. The grey solemn border wall was re-appropriated and its meaning transformed and domesticated, so as to suit the surrounding urban fabric – similarly to what used to be done to the Western side of the Wall, which before 1989 was often covered in colourful graffiti, tags and political slogans, standing in stark contrast to its Eastern solemn counterpart.

A piece of the Berlin Wall to go, please

Meanwhile, throughout the 1990s and up to this day international institutions have been acquiring their own components of the Wall in order to exhibit them as symbols of either the Cold War or its end in 1989 – or both. From Russia to Hawaii, from the Sanctuary of Fátima in Portugal to the Peace Park of Uijeongbu 30km south of the North- and South Korean border, to Hungary, Romania and Stocznia Gdańska in Poland, countless of the historical slabs are traceable worldwide. Although there is no exact registry available of where to find the original segments of the Berlin Wall, it is obvious that the monument has been detached from its historical environment and thus re-contextualized as a portable relic.

Nowadays, it is surprisingly easy to get your very own piece of the Berlin Wall. On numerous online websites, at stalls near historical sites, even in official souvenir shops across the city, people can buy (allegedly) original fragments of the wall that separated Berlin into two parts. Whereas there is a range of sizes and prices – some companies even sell entire slabs of the Wall for a four-digit fee – each piece goes with a certificate confirming its authenticity. However, no institution has the authority to issue such documents. As most of the officially demolished segments of the Wall were afterwards shredded and used for road construction, it is safe to assume that a considerable amount of these souvenirs is fake.

Berlin Wall: global lieu de mémoire

30 years after its fall, the meanings given to the Berlin Wall seem to be full of contradictions. On one hand, its tearing down has gotten equated with the peaceful revolution in Germany – or even the whole former Eastern Bloc. Its significance often gets universalized to such an extent that it begins to overshadow other equally important political transformations of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe and sometimes is even treated as a symbol of freedom and liberation in general. On the other, the Berlin Wall continues to stand for oppression and illiberal living conditions in GDR, as well as other authoritarian and totalitarian regimes.

As cultural studies scholar Frederick Baker argues, the Wall has been changed into “a ‘collective symbol’, an easily identifiable, emotionally charged, physical embodiment of the political system which made it – both symbol of tyranny and symbol of liberation from tyranny.”3 This significant double meaning, acting here as two sides of the same coin, is often being conveyed onto remaining pieces of the Wall – be it real or fake ones. Hence their captivating symbolic strength and popularity, which allowed them not only to become renowned Berlin memorial sites, but also to be distributed beyond regional borders as private souvenirs or historical artefacts, being put on display across the world.

Written by Stefanie Knossalla; edited by Jagna Jaworowska

1. The phrase used by art and architecture historian Axel Klausmeier (Klausmeier 2009: 97).

2. Six years ago, investors of luxury apartments started to remove segments of the East Side Gallery in order to have enough space for a construction site. This triggered international protests carried out under the slogan: “Rescue the National Monument East Side Gallery! No luxury housing on the former ‘death strip’.” Although demonstrators managed to temporarily stop the investors’ plan, parts of the gallery had been already gone. As the attack on the murals seemed to repeat in the beginning of 2018, powerful demonstrations finally led to an agreement: the property around the Wall’s section in question has been handed over to the Berlin Wall Foundation. The NGO is responsible for the further preservation of the historical site.

3. Baker 1993: 725

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baker, Frederick. ‘The Berlin Wall: production and preservation and consumption of a 20th century monument’. Antiquity Publications 67, 1993. 709-733

Huet, Donatien. Interaktive Karte – Wohin ist die Berliner Mauer verschwunden? 29. Oktober 2014. Accessed on 20.09.2019: https://info.arte.tv/de/interaktive-karte-wohin-ist-die-berliner-mauer-verschwunden

Klausmeier, Axel. ‘Interpretation as a means of preservation policy or: Whose heritage is the Berlin Wall?’ In: Forbes, Neil; Page, Robin; Pérez, Guillermo (eds.): Europe’s Deadly Century Perspectives on 20th century conflict heritage, Swindon, 2009. 97-105

Klinge, Sebastian. 1989 und wir: Geschichtspolitik und Erinnerungskultur nach dem Mauerfall. Bielefeld, 2015

Nooke, Maria. ‘Vom Mauerbau zum Mauerfall – Kurze Geschichte der Teilung‘. In: Kaminsky, Anna (ed.): Die Berliner Mauer in der Welt, Berlin, 2009. 8-23

Schmidt, Leo. ‘Symbol und Denkmal. Die Karriere der Berliner Mauer nach ihrem Fall‘. Tagungsbeitrag: Der Mauerbau 1961. Kalter Krieg, Deutsche Teilung, Berlin. 16-18. Juni 2011

BERLIN WALL FOUNDATION 2019. East Side Gallery. Accessed on 25.09.2019: https://www.eastsidegalleryberlin.de/en/

BERLIN WALL MEMORIAL. Accessed on 25.09.2019: https://www.berliner-mauer-gedenkstaette.de/en/