A recent two-day international gathering at the Sybir Memorial Museum in Bialystok1, Poland recently brought together a group of museum professionals and academics from Columbia and Chile in South America, South Africa, Rwanda, Algeria, and Stanford University in the United States. This experienced group shared their insights and the challenges they are currently facing in dealing with the legacy of trauma in their own countries.

The Sybir Memorial Museum, provided an appropriate location, and a space that recognizes the pain, loneliness and resilience of victims and survivors, Jews who were deported from the ghetto in Bialystok to the extermination camp at Treblinka and the inhabitants of the Bialystok region who were deported by Soviets to Siberia in 1944.

Focused on the impact of ‘what happened, trauma flows like an underground river in the lives of those who experienced the physical, psychological, and sexual violence which had followed violence, war, colonialism, and deportation.

Trauma

Dr Gabor Mate2, a Hungarian-Canadian physician describes the experience of trauma as ‘It is not what happens to you, it is what happens inside of you as a result of what happened to you’ which shifts the focus from the traumatic event itself to the individual's internal experience, highlighting the importance of addressing the emotional and psychological impacts to facilitate healing.

The ‘unspeakable’ which refers to the results of the violence, is often gendered and allied to prejudice, rape, humiliation, oppression, shame and death which people bore in South Africa, Rwanda, Columbia, Chile, Algeria and Central and Eastern Europe and which shaped their struggle for acknowledgement, justice, reparation, reconciliation and healing.

Through their work with victims and survivors, they shared the different methodologies they had discovered and developed to help people deal with the past and find peace in the present. They spoke about the importance of therapeutic support, peace education, art, and music which needed to be delivered with people rather than for people.

South Africa

The Cape Town Holocaust and Genocide Centre was set up in 1999 to commemorate victims and survivors of the Nazi regime and the numerous genocides that have occurred since the Holocaust. Former President Nelson Mandela made a strong connection between the discrimination, prejudice, and the killing of black South Africans with what Jews had suffered. This drew attention to the dangers of prejudice, racism, silence, and indifference which can affect any society.

Introduced into the school curriculum in 2007, it started a reflection and an ongoing discussion on how race is constructed and how it can be weaponized to kill and persecute regardless of which it is White/Black racism or Black/Black racism or fueled by religious fundamentalism.

More information here.

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile

This was built out of a sense of moral reparation for the repression caused by Augusto Pinochet and the Military Junta which ruled Chile from 1973-1990. The museum provides a dedicated space to preserve the memory of the people who were subjected to human rights violations committed during the country’s military dictatorship. In April 1990, a new democratic government created the National Committee of Truth and Reconciliation which investigated the crimes committed during the dictatorship, which included those killed, exiled, tortured, and the disappeared. Today it also has a strong focus on engaging the police and the military in the museum as these were key to maintaining the dictatorship for many years.

It focuses on innovative ways to attract young people, often marginalized, by making the museum a welcoming place not just about the past but a space for events using art and contemporary music. This, they find, encourages people who may never have visited the museum to engage with the past in the present.

More Information here.

National Museum of Moudjahid Algerian Museum

Focused on the impact of colonialism, this museum focuses on resistance to French colonialism, the empowerment of youth, the recovery of Algeria’s past before colonialism and its journey towards independence. It also allows the creation of a safe space and an exploration of how colonialism can unconsciously shape the future without awareness. It is strongly focused on promoting the importance of democratic values for the future for young Algerians.

More information here.

Columbia-House of Memory (2006)

While conflict and violence are still part of daily life in Columbia, South America, the House of Memory provides a living space for memory and dignity for victims of the conflict and their families. It acknowledges the courage and the memories of those that suffered and encourages listening, writing stories, painting and artistic expression which can help people to process the impact of living with trauma. It creates a safe space, a place of symbolic reparation and uses a range of methodologies. These include, psychosocial accompaniment integrated into testimonies, testimony as a relational and ethical encounters, respect for non-linear and fragmented stories, use of art therapy and circles as healing mechanisms. At the core of everything they do is the dignity and care of people who come to the museum.

More Information here.

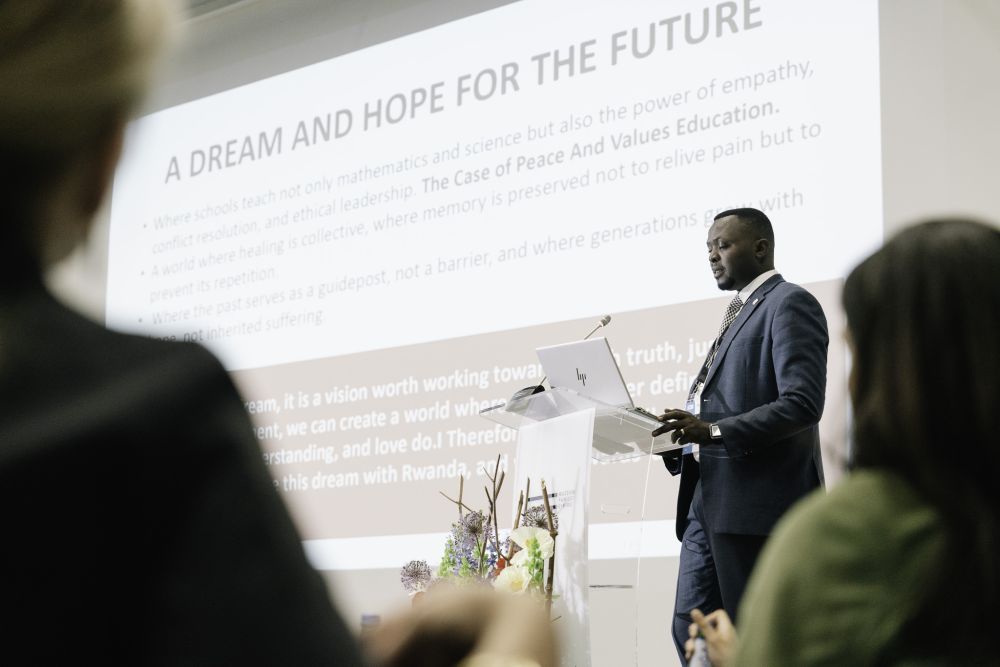

The Kigali Genocide Memorial

Located in Kigali the capital of Rwanda, every young person today in Rwanda continues to be connected to the legacy of genocide and anti-Tutsi persecution, with no community left untouched. Cultural norms often discourage open conversations about such painful experiences which are commonly referred to as ‘unspeakable.’

Rwanda had about two million perpetrators, individuals or neighbours who planned and executed mass rapes, killings, and lootings. Faced with the ‘unspeakable,’ silence often felt like an easier choice, but they also found that choosing silence left the next generations with unanswered questions, unanswered identity crises and deep psychological wounds.

Between 150,000 and 250,000 women were raped during the genocide, often multiple times by perpetrators. This has resulted in around 25,000 children been born because of the genocide, now in their thirty’s these young people still grapple with painful questions about identity and belonging. How Rwanda coped with the wholesale destruction of minds and bodies has been well documented, the setting up of the Gacaca courts3 to cope with the thousands of violations, often by their neighbors, were local courts which brought perpetrators before the community to confess their deeds.

The provision of therapeutic services, peace education courses, facilitated dialogues, and healing processes are ongoing.

More Information here.

Polish Women and Deportation

It has taken a long time to publicly acknowledge the additional burdens placed on women living with violence, poverty, and conflict globally. Social and religious biases, stigmatization, silence, humiliation, shame, and underreporting have contributed to the voices of women not being heard or having been actively silenced.

Stereotyping women as ‘selfless patriotic mothers’ failed to capture the complexity of women’s lives, creating a trap for Polish women4 who were deported to Siberia or further to Kazakhstan by the Soviets. Roles were gendered and while it was acceptable for men to take up arms to fight for the Fatherland which many women also wished to do, they were prevented because of caring responsibilities.

Women often became the sole carer for children whose men were often in prison or dead or in the army or disappeared or had deserted them. Being left poor and isolated made women vulnerable. Many women were forced to work which meant that they either had to leave their children in the care of other children or send them to orphanages. Women were also under pressure to raise patriotic children, maintaining their religion and language and sometimes refused to send them to Soviet schools. Fear of Sexual assault and pregnancy was allied with shame and humiliation, stigma and isolation by husbands or families. This could not be spoken about and was often denied as a community and was ascribed to non-Polish women only.

The impact of Sexual abuse

‘Only those who are victims of such pain can talk about sexual abuse because there is so much trauma that I couldn’t say what hurts more, the abandonment of a state, the silence of a frightened country or being violated and having to remain silent, To keep quiet about so much pain, this disgust that tortures us more every second of our lives, the right to be heard by everybody…those that have a voice, that remain silent to defend the cynicism of these savage brutes who only think of hurting the weakest. I want to scream.’

Translation from Spanish

Conclusion

The cry ‘Never again’ seems empty when, despite what we have learned, we repeat the same again with another group, at another time and in another place.

And yet we have learned that trauma is not a terminal disease, with help, it can be integrated into experience helping to find meaning and life again.

While museums are valuable reminders of the past, these museums remind us that despite ethnic and national differences, the desire for acknowledgement, justice, freedom, acceptance, dignity, and respect are central to being human.

Today, they can provide a neutral space in a polarized world where people can gather to discuss the past if needed, a place of hospitality and safety to meet others using words, music, or art and to honour silence together when nothing else helps.

Written by Barbara Walshe

1 The Sybir Memorial Museum based in Poland is devoted to people who, from the end of the 18th century until the middle of the 20th century, were deported deep into Russia and deported into the Soviet Union sybir.bialystok.pl/en

2 Maté, G. & Maté, D., 2022. The Myth of Normal. Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture. 1st ed. London: Vermillion.

3 Rwanda: Gacaca: A question of justice

4 Jolluck, Katherine R, Exile, and Identity (2002). Polish Women in the Soviet Union during World War 11