‘Purchasing and bringing food into the ghetto is forbidden’: Ways of Survival as Revealed in the Files of the Ghetto Courts and Police in Lithuania , 1941–44

ABSTRACT

The article focuses on the importance of work in the supply of food into the ghettos of Lithuania. Files of the ghetto courts and police reports used in this paper shed light on the reality of ghetto life and illustrate how individuals dealt with the situation and tried to get additional food. It is obvious that micro-networks (family, neighbourhoods and co-workers) were an important means of support for the individual within the context of ghetto societies. Normality and everyday life therefore reflect the reality of a forced society whose social differentiation was primarily based on a single criterion: access to food.

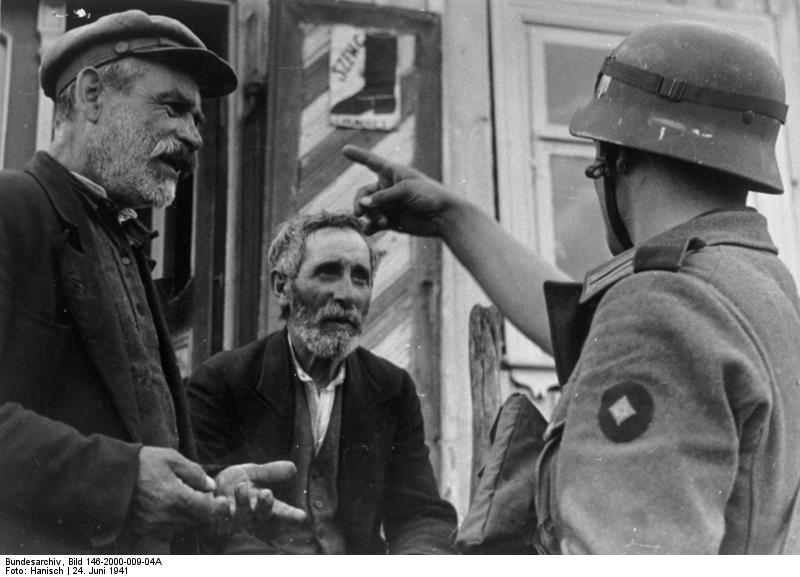

The idea of a ghetto still connotes the idea of a zone hermetically sealed off from the outside world, where people are fully separated from their previous environment. It has been repeatedly pointed out in recent decades that a special form of everyday life and normality existed in this extreme situation (Dieckmann and Quinkert 2009, 9–29). Research has increasingly followed this approach in recent years, as several publications have been added to existing memoirs of everyday experience, which are devoted in the form of anthologies to daily life in the German Reich (Löw 2014) and Eastern Europe (Hansen 2013). Monographs have also been added: Andrea Löw describes the situation in the ghetto of Litzmannstadt (Löw 2006), while this author has dealt with everyday work in the ghettos of Lithuania (Tauber 2015). The following may prove the potential of addressing such everyday issues and once again show that the history of the ghettos in Eastern Europe still has certain gaps that need filling. The genesis of this particular form of normality is closely tied to work of the Jewish population provided for its German masters. In most ghettos such work was performed outside the ‘Jewish district’, so it was possible for many Jews to establish contact with non-Jewish people in the immediate vicinity. At the same time, Jewish councils, appointed by the Germans or selected by the Jews on Germans’ orders, formed an infrastructure to regulate and control labour and its internal management within ghettos.

This development also took place in the three major ghettos in Lithuania. Since extensive resource materials exist in Yiddish, Lithuanian and German, traditions can be described relatively well (except for the ghetto in Šiauliai). Deep insights into ghetto life can also be found in the diaries of Herman Kruk in relation to Vilnius (Kruk 2002) and Avraham Tory with regard to Kaunas (Tory 1990). In addition, early reports and accounts (Fun letztn Churbn 7 and 8; Gar 1948; Balberyszki 1967; Dworzecki 1948; Shalit 1949) have particular significance and contributions in a two-volume memoir (Sudarsky 1951) are also important. There are complete histories of the three ghettos in the encyclopedias of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem. They contain research on the ghettos in Lithuanian, Israeli and German (e.g. Bubnys 2014a and b; Kaunas 2014; Vilnius 2013; Porat 2009; Levin 2014; Dieckmann 2011; Tauber 2015). The histories of the Jewish councils by Isaiah Trunk (Trunk 1972) and the emergence of the ghettos by Dan Michman (Michman 2011) remain the seminal works on this subject.

After the mass murders of late 1941, survivors were put to work in the ghettos in Kaunas, Vilnius and Šiauliai where the interests of the German administration and armed forces, as well as those of the Jewish councils, were mutually dependant: the former were interested in labour of all kinds by those willing and capable, whereas the latter, in turn, saw work as a means of survival, guaranteeing the ghettos’ continuing existence. Moreover, Jewish labourers in Lithuania had to be paid by their ‘employers’, enabling Jewish councils to provide at least some form of rudimentary aid through taxes or direct salary deductions to those who were either too old or too ill to work.

Work also offered a way for those in forced labour to improve their own wretched living conditions. Naturally everyone was interested in obtaining more food or goods for their families or themselves through official allocations in order to relieve their misery. Inevitably activities clashed with the regulations of the occupying forces; sometimes they involved fraudulent behaviour or sparked conflicts with Lithuanians or other ghetto residents. Such incidents are evident in the criminal investigations of the ghetto police or in the files of internal ghetto courts that meticulously documented their inquiries and judgements in German, Lithuanian and Yiddish. These materials, which are now housed in the Lithuanian Central State Archive, shed light on the reality of ghetto life and illustrate how individuals sought to cope with the situation. Here I present some of these files, supplemented with memoirs and documents, and place them in a broader context.

All ghetto inhabitants were, as I stated, keen to work because the evidence of activity increased an individual’s food-ration entitlement, e.g. in Kaunas the ration was doubled (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 35, p. 236). Especially desirable were positions in work brigades that allowed you to leave the ghetto because you could then transact with locals. However, it did not always go as planned. In the spring of 1943, the head of the investigation section of the ghetto police, Giršas Volpertas, wrote a report on a related incident involving fraud. Baruchas Kovenskis, a member of a work brigade in Kaunas, reserved 5 kilograms of butter with a Lithuanian woman and wanted to pay and take it the next day. When he appeared on 1 May she stated that his colleague, who she believed had come on his behalf, had already picked up the butter. Since the woman did not want to issue the goods, Kovenskis’s supposed colleague finally left her RM 325 and disappeared with the butter (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 145, p. 35). The Lithuanian woman believed the claim of the man because he personally knew Kovenskis and his statement that Kovenskis could not come because he had to work that day at Aleksotas airport was a commonplace occurrence in the assignment of brigades. Often, people from city brigades were indeed divided up at short notice for hard work at Aleksotas outside the city (Tauber 2015, 190–95). On the basis of a testimony by Ilija Kaganas, a member of Kovenskis’s work brigade, it turned out that the fraudulent buyer was Arkadijus Buršteinas, who Volpertas summoned for interrogation (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 145, p. 35).

Buršteinas, who was questioned on 4 May, did not deny the incident, but believed to be in the right as he had already negotiated with the Lithuanian woman in front of Kovenskis, but failed to agree on a price: he offered RM 62 per kilogram, whereas she demanded RM 65. Having failed to force down the price, he left. Kovenskis witnessed this and ultimately paid the woman her desired price, but only because he wanted to snub Buršteinas. Enraged, Buršteinas had then taken a portion of the butter, but stated that he could not recall whether he had claimed to have come on Kovenskis’s behalf. However, he was only able to sell 2 kilograms in the ghetto and make a profit of RM 40, which he donated to a good cause.

The investigator recorded his findings and conclusions. Kovenskis had bought a total of 15 kilograms of butter in Kaunas, but only took 10 kilograms and wanted to pick-up the remaining 5 kilograms the following day (despite bribable German, Lithuanian and Jewish ghetto guards, the smuggling of food into the ghetto was officially forbidden and entailed considerable risks, as discussed below). Even if Buršteinas had to pay the purchase price owed to the suspicious Lithuanian, it was nevertheless assumed that he had wanted to acquire the goods fraudulently. This assumption is also supported by the fact that it was very difficult to find food in the city in the week of the incident between Easter and 1 May. The fraudster also made a profit. The investigators reached the conclusion that what mattered to Buršteinas was his own enrichment rather than settling a personal score with Kovenskis (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 145, p. 35 f.).

These events provide initial insights into ghetto reality. The quantities reveal that the above incident not only concerned the purchase of food for the buyer’s own use, but that the butter was bought with the intention to resell it in the ghetto (Gar 1948, 119 f.). The fact that the Lithuanian seller was not prepared to budge from her price showed there was a demand. Finally, it seems that Kovenskis was able to smuggle 10 kilograms into the ghetto in a single day, even though returning work gangs were searched at the ghetto gate. The way Buršteinas’s fraud was recorded shows that such events were by no means an exception, but reflected an everyday aspect of food procurement and survival strategy. The fact that trade between Jewish workers and the Aryan populace was a mass phenomenon is evidenced by urgent instructions of the German civil administration passed through the Kaunas ghetto police to work gang leaders in July 1943, that is for ‘workers not to leave their work places and engage in trade und hoarding’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 19, p. 126). The regularity of purchasing additional food is also clear in memoirs written after 1944:

Early in the morning, after the night shift, they ordered us to walk back to the ghetto [...] farmer wives sold their own grown vegetables there [at the former Jewish fish market outside the ghetto]. Whenever the opportunity arose, we stole away from the column, disappearing quickly between the stalls and grabbing a cabbage or other vegetables in exchange for some money before rushing back into the procession’ (Faitelson and Widerstand, 53).

M. Chevasztein in Vilnius had similar experiences:

I used the lunch break or other free moments to make purchases. For this purpose, we ran into the next Polish huts. We bought bread, cheese, cucumbers, tomatoes, potatoes, etc. at a fairly high price [...] After work, we returned home with these purchases. We gradually got to know the guards and they allowed us to buy something (EK 3 Legal Proceedings, vol. 4, p. 1571, German translation of the book Geopfertes Volk – der Untergang des polnischen Judentums [Sacrificed people – the demise of Polish jewry] by M. Chevasztein).

Jozif Gar, who already reported on the events in Kaunas in the 1940s, emphasized that work outside the ghetto was the best and safest of all possible ways of procuring cheap ‘food’ (Gar 1948, 103, 118). In the summer, there was another option, as work in the countryside gave opportunities to forage for food and procure fresh vegetables and fruit (Gar 1948, 118). In this respect, the call for reflection at harvest time published in late September 1942 in an editorial of the Vilnius ghetto newspaper In diesem Moment has a special double meaning: ‘We should not stop lifting our eyes to the sky’ (Feldshtein 1997, 137).

While such procurement practices were commonplace, they could quickly lead to trouble. Even when Salomon Baron had permission to make purchases from the Local Commissioner of Kaunas, something soon went wrong:

On my arrest on 12 December the [...] Kaunas police took my money – approximately Rbl. 1,200 – as well as a brown leather wallet, pocket knife and a pocket watch. On my release from prison on 20 December, these things should have been returned to me, but the officer was not there at the time and I could not have them.

Baron was not the only one affected, which he made clear in his request to the chief of the ghetto police: ‘the money is from aircraft wage [meaning: work at the airfield in Aleksotas] for my family. I kindly ask you to fulfil my request because we have been left without money’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 1, b. 9, p. 24, front and back page). Such family networks were an important structural feature of the ghettos, as only cooperation and loyalty within a narrow (family) circle gave people the strength to cope with life in the ghetto. Tight communities were also formed through forced cohabitation with others in crowded houses or working closely in a brigade.

At times, people received small rewards or gifts from supervisory personnel within the ghetto, as did Ida Kaganaitė, who nevertheless had the misfortune of being found with two loaves of bread and a lemon during a check at the ghetto gate by her German masters. Meticulous findings of the ghetto police eventually led to the following conclusion:

I established that she is engaged in clean-up work at the airfield. Above all, this is laundry work for workers or general construction foremen [...] it has repeatedly come to the fore that also soldiers [...] brought her laundry for washing [sic.] and that she received bread or small packets of baking soda – lemons – as a reward’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2. b. 19, p. 124).

Thus, the Jewess was spared the punishment imposed on other apprehended smugglers, which was usually work on Sunday (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 19, p. 129). Also, the 47-year-old Pesė Perkienė fell into the hands of the ghetto police under German security police’s orders because she had brought food several times at a shop in Kaunas and was denounced. Not only were Jews forbidden to visit a ‘normal’ food store, but it seems that Perkienė was not wearing the Star of David. In another case, a Jewess was punished by being held under arrest for four days or fined RM 20 for merely ‘walking without a Star of David’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 3, b. 52, p. 340). When questioned on 12 May 1942, Perkienė claimed not to have taken off the Jewish star or to have paid anything for the food. Rather, she repeatedly referred to her former Lithuanian neighbour, Dainauskienė: ‘She sold me no [food], but out of pity gave my children some potatoes, cereals, bread and cabbage. I have no money to buy food and was therefore forced to beg from my previous neighbours’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, fol. 90). A Jewish woman under arrest summed up the reality of food procurement in a single sentence: ‘I only know that my children are starving and that I had to get some food for them’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, p. 90, back page). The woman questioned by the ghetto police had four children, the youngest an eight-year-old boy, a fourteen year old, and two over the age of sixteen who were obliged to work.

The treatment of people from the ghettos varied, as the examples of Ida Kaganaitė and Pesė Perkienė show, depending on their place of work and how they were supervised. Access to food and trade with the local populace were directly linked. Bolt, an engineer at the construction company Grün und Bilfinger in Kaunas, made a name for himself as a Jew hater: ‘There was very heavy work and people could exchange things only under extremely difficult conditions, as Bolt always watched and then took food away from the people or notified the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; Security Service) or City Commissioner’ (EK 3 Legal proceedings, vol. 3, 817). In turn, Oskar Schönbrunner, a paymaster at Field Headquarters 814 in Vilnius, was honoured as a Righteous Among the Nations in 1977, as two survivors testified after the war: ‘Schönbrunner helped the Jews working for him by providing benefits that were punishable by the SD; these included support through food, wood and other items of daily use. Schönbrunner also improved the living conditions of the Jews by building additional factory kitchens’ (EK 3 Legal proceedings, vol. 4, p. 1455). Another way of food procurement associated with work in cities was particularly dangerous. As the people’s misery was immense, there were those such as Jona-Dovydas Rubinas, who was caught stealing at the army-catering store on 30 December 1942. The upper paymaster of the army-catering store in Kaunas reported the theft to the SD (Security Service) and the ghetto police and requested that the thief be punished (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 19, p. 243). In his interrogation, Rubinas outlined the reasons for what he did:

I have worked at the army-catering store for about two weeks. I previously worked at the airfield. During my entire time at work I have never done anything wrong. I have performed heavy work the whole time and had to support myself with my primary and supplementary rations. Today, I worked at my job as usual [...] loading food. Given the poor nutrition of my family, I succumbed to the temptation to take two tin cans from the load. I did not know what was in them. I just knew that there was food’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 19, fol. 244).

Nothing more is known about the punishment of Rubinas, but in similar cases beatings, additional work and the temporary withdrawal of reference cards were imposed (Tauber 2015, 294–313).

Finally, the attempt to provide food could also prove fatal as in the case of Nachmanas Srokas (aged twenty-six) and Joselis Fridas (aged forty-five), who were shot at Aleksotas airport by German guards on 23 May 1942. They ostensibly sought to leave the area in order to buy food (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 33, p. 15, back page). It was also life threatening to smuggle food through the ghetto fence, and not through the ghetto guard post. On 28 February 1942, the Jewish ghetto police reported in its daily report to the chairman of the Jewish Council: ‘I report to you that yesterday, on 27 February at 20:00, citizen Balkindas Jankelis was shot at the intersection of Stulginskis and Linkuva Streets outside the ghetto limits, as facts show, while pulling a small sledge with food.’ The Lithuanian guard justified his action by stating that the deceased fled after his call and also that he did not respond to several warning shots (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 33, fol. 300, p. 305).

However, a contact zone at the ghetto fence was soon created. The situation in Vilnius was especially pragmatic because here the ghetto was in the middle of the city:

an agreement was reached with non-Jewish neighbours whose windows faced the ghetto and trade began. Initially, this trade was very simple: a noose was lowered from a window and ghetto inhabitants tied money, valuables or clothes to it. The neighbours took it on themselves and lowered goods [meaning: food] on the same rope into the ghetto [...] Later the trade was done on a larger scale. Dozens of loads were smuggled night after night with all kinds of goods through the attics of 21 Dajtsche Street [...] through the Maline [underground hideout] on 3 Straschun Road (Sutzkever 2009, 97).

Also, in Kaunas, a kind of professional trusteeship evolved: anyone who wanted could give goods to middlemen, who then sought to sell them to the Lithuanian population at the fence. Berelis Migancas was one of the negotiators. He was sentenced in the autumn of 1941. The 21-year-old was withdrawn from work at Aleksotas airport as well as in a city brigade because he drifted elsewhere: ‘when questioned in court he admitted that he used free time when he was neither at the airfield nor in the city to trade items for food for other people at the fence and for profit’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 51, p. 65). This example shows that individual trade was punished within the ghetto when it conflicted with the ghetto community’s group obligation to work. The German masters punished such offences less than the ghetto authorities. In the case of Migancas, the ghetto court gave a harsher punishment, since the young man lived alone and did not have to provide for a family.

Such trade was also brisk in Vilnius, hence, the officer for Jewish affairs of the Lithuanian city administration proposed resuming strip corridor patrols along the ghetto to the German occupiers at the regional station in December 1941: ‘it has also been noticed that the Jews even use twilight [sic.] for the receipt and delivery of different goods from unauthorized persons through the insulation [meaning: the fenced-off ghetto border]’ (LCVA R-643, ap. 3, b. 194, p. 167). Shalom Eilati, born in 1933, watched in Kaunas as his mother traded with a Lithuanian woman:

across from us [...] stood a Lithuanian woman, seemingly without purpose. My mother would wave her hand or flap a woollen skirt or a colourful towel up and down to arouse her interest [...] The gentile woman would [...] begin waving her own items of trade – eggs, butter and meat. Then the vocal transaction would begin. They haggled over the terms of exchange. When they agreed, both would look hastily left and right, spring simultaneously to the fence, trade the goods in their hands in an instant and retreat to their starting corners. Sometimes the lengthy bargaining would end without a result (Eilati, River 32 f.).

Such form of ‘intermediary trade’ between the ghetto and the ‘Aryan’ environment was no exception. During the first months of the ghetto, a certain kind of ‘working from home’ also developed in Kaunas. Its success depended on goods being transported backwards and forwards between their ‘manufacturer’ and non-Jewish customers. It was based on demand for most basic commodities, such as headscarves, aprons and hats that the Lithuanian population lacked. Bed sheets or white linen, which had often been dyed to make them more attractive, were sought after. Repairs and alterations were also common (Tauber 2015, 251 f.; Gar 1948, p. 121). Another possibility was the skilled craft works of German and Lithuanian masters, which led to a warning sign being posted in the ghetto on 13 May 1943:

Lately, Jewish workers have taken various items from their work posts such as shoes, watches and other items for repair in the ghetto [...] Jewish workers are forbidden to take any items from their work posts into the ghetto for repair. If such repairs are proposed, Jewish workers are to be politely told that the acceptance of such work is strictly prohibited (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 1, fol. 22).

The early involvement of young people in the work process had special strategic importance. The Jewish Council in Kaunas reported in its ‘overview of the activities of the council of elders’ in June 1942: ‘a new development in work is the presence of more than 200 young workers gardening outside the ghetto [...] This young group has proven itself and does a good job’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 40, p. 73). It was crucial that also one half of these children received additional food as workers. Since work offered the possibility to trade and to better food, there were also volunteers such as the fourteen-year-old son of the aforementioned Pesė Perkienė, who was hired at the dreaded Aleksotas airfield.

No one was immune to terrible consequences, even those who supposedly had easier access to food. This was the case of the Jewish cart-driver Jankelevitz, who on 1 May 1942 was reported missing by his wife after being arrested fourteen days earlier in the courtyard of the Lithuanian meat cooperative Maistas. The 36-year-old, as told by a ghetto resident who accompanied her husband, reported that the stolen meat was discovered during a cart search and that her husband was then arrested. In reality, the other riders wanted to exchange the meat for a dress and that her husband had nothing to do with the entire affair. However, interrogations of the Jews involved in the ride to Maistas painted a rather different picture. The meat was bought from an unknown Lithuanian, who was also at the court with his team. Three kilograms were traded, as there was not enough money for more. The deal went smoothly until Jankelevitz was denounced and accused of theft by a Lithuanian employee at Maistas (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, fol. 39 f.).

Jankelevitz and his colleagues were in a privileged position because they were officially allowed to leave the ghetto regularly and move about to provide social welfare for the ghetto, with the permission of the German ghetto guards. It was certainly part of their regular activity to procure additional food by visiting Maistas, especially to meet Lithuanian farmers, who were not averse to trade, in the courtyard. Also interesting in this context was the task of the Jewish drivers. They brought feathers to Maistas (there was a feather-sorting section at the ghetto) and exchanged them for bones, which were then brought into the ghetto to make soup for the needy (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, fol. 41). All ghettos in Lithuania had soup kitchens and other social institutions – albeit makeshift – to provide warm soup or essential material resources (e.g. firewood in winter; Tauber 2015, 285–6).

Cooperative relationships existed beyond the already-noted micro-networks found within a family environment, as with the soup kitchens, but they were mostly limited to those belonging to the same status group or class. The work brigades entrusted one person to execute large orders on behalf of them all. The advantage of this large-scale food procurement was usually a lower unit price, less risk of discovery and being able to rely on the middleman’s good contacts. But disagreements could also arise, as recorded in documents of the ghetto police. The 37-year-old worker Dovydas Tamše, who offered to buy sugar for members of his brigade, was considered suspect in the autumn of 1942. An investigation revealed that Tamše was likely to have embezzled money because Tamše’s claim that his Lithuanian partners hit him on the ear was hardly credible. The initiation of proceedings by ghetto authorities took place under the force of the Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Lithuania with the telling note that such offences must be especially prosecuted under ‘current ghetto conditions’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 145, p. 92 f.).

The benefits of work for individuals outside the ghetto meant that it was hard to be a permanent member in a city brigade. It was the brigadier who decided on who worked in the group, and thereby had access to obtaining food; he was the ‘spokesman’ and foreman of the group, who was the primary contact for Germans and Lithuanians at a workplace as well as for the internal ghetto organization. Isak Rozalsky, a merchant in Kaunas before the war, noted that the brigadier of a well-established brigade for constructing garages in Kaunas often selected even more workers for his group at the ghetto gate (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, fols 77 ff.):

In September 1941, I noticed Tomašauskas at the ghetto gate [...] who came from town. At my request, he temporarily hired me as a worker at the garage building in Kauen [...] Since I always wanted to work in this brigade, I offered Tomašauskas my brand new suit that I estimated to be worth RBL 1,500 for a price of RBL 600. Tomašauskas agreed, took my suit and gave me two RBL 200 notes. He has not paid me the rest to the present day.

Testimony gathered by investigating bodies in the ghetto repeatedly showed that Tomašauskas did not only cheat Rozalsky, he initiated a change of workers in order to receive payment to work in the brigade (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 69, fols 80 ff.). Such behaviour was far from the rule. On the contrary, many brigadiers were willing to accommodate their workers and also to cover for them. The incensed Kaunas ghetto police summed it up: ‘Inspections revealed that persons listed as not working on given days showed a note from the column head or a work card as evidence that they did indeed work on such days. Such evidence cannot reflect reality’ (LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 52, p. 141). Evidence of work was vital for every ghetto resident: better accommodation and remuneration depended on entries in work documents and the employer payroll (Tauber 2015, 226–48).

The above networks for transporting food to the ghetto were of great importance. Passing the ghetto gate was always a gamble: smuggled goods could be confiscated here. The situation was particularly problematic if Germans inspected the Jewish ghetto guards. This always had direct impact on the precarious economics of the ghetto. In good times, the price difference between ghetto and city goods was relatively small so that many people gave up smuggling and bought directly in the ghetto (Gar 1948, 118 f.). However, goods from outside the ghetto usually came via the ghetto gate. Officially, representatives of the Jewish labour office aided by the ghetto police were responsible for the collection and control of departing work columns. Jews, as already mentioned, were not allowed to return to the ghetto with any food or other items (Gar 1948, 340). As a result Jewish gate guards played an essential role and could keep some of the goods back for themselves. This limited smuggling opportunities for individuals: they could only hide food on their body and in their clothing (body-binding, so-called compresses, or hiding items in their shoes were popular in their attempt to bypass a superficial search). Dishes that were allowed to into the ghetto for on-site feeding could have a double bottom in which a piece of bacon, butter or margarine could be concealed (Gar 1948, 103). The great number of returnees each day (several thousand in Vilnius and Kaunas) made it impossible to search every individual (Gar 1948, 103, 340 f.). The Jewish councils were well aware of the occasional questionable behaviour of Jewish gate guards. In April 1942, Fried, the chairman of the Jewish council in Vilnius, filed a fiery complaint against the ghetto police chief, Gens: ‘Incidents occur during ghetto entry involving gate guards and those entering. Frequently, they are not caused by formal matters, but by careless dealings and improper edginess of gate guards’ (Balberyszki 1967, 430). However, smuggling opportunities made city work particularly appealing. Such work, as Jozif Gar states, ‘made the ghetto Jews privileged and secure [...] allowed them to eat better and to always have a few spare Marks [in the sense of freely available]’ (Gar 1948, 104).

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that professional smugglers soon organized themselves in the ghetto, offering their services for a commission. A black market thus developed, which now operated on a grand scale in which all ghetto institutions, including the Jewish council (for the soup kitchens), as well as German and Lithuanian guards participated (Tauber 2015, 257 f.). Hermann Kruk, the chronicler of the ghetto in Vilnius, summarized it succinctly: ‘So, the smuggler has the possibility of smuggling and the ghetto has the possibility of getting bread’ (Kruk 2002, 287).

A certain grey area appeared in the context of ghetto societies, which was a constant cause of great distress and danger to individuals. The acquisition of food outside the ghetto was so important as a strategy of survival that it always entailed many uncertainties: this could be a denunciation or the intervention of a zealous Lithuanian police officer, German engineer or employee of a meat cooperative. Or, it could be a close inspection at the ghetto gate, in particular, by German ‘authorities’ or it could involve fraud or theft inside or outside the ghetto. Normality and everyday life, therefore reflected the reality of a forced society whose social differentiation was primarily based on a single criterion: access to food.

Translated from German into English by Edward Assarabowski

Joachim Tauber

Joachim Tauber obtained his PhD from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in 1989. He has served as the director of the Nordost-Institute Lüneburg (IKGN) at the University of Hamburg since 2010. He read modern history at the University of Hamburg, where he was appointed as a private lecturer upon completion of his postdoctoral qualification with a monograph about the Jewish working force in Lithuania 1941–44. His research interests include the history of German–Lithuanian relations, the German occupation of Eastern Europe in the First and Second World Wars and the Holocaust in the Baltic States. He has published many articles, and his most recent book is: Arbeit als Hoffnung. Jüdische Ghettos in Litauen 1941–1944 [Work as hope. Jewish ghettos in Lithuania 1941–1944] (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2015).

List of References

Sources

Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden. Dept. 461.32438, EK 3 (Legal proceedings).

LCVA R-626, ap. 1, b. 4, p.12 (Quote in the title of this article)

LCVA R-643, ap. 3, b. 194 (City administration of Vilnius, correspondence with Jewish councillors).

LCVA R-973, ap. 1, b. 9 (Correspondence of the Kaunas ghetto police).

LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 35 (Weekly reports of the Jewish ghetto police in Kaunas).

LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 19 (Enforcement orders of the Jewish ghetto police – Central Office, Kaunas).

LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 33 (Weekly reports of the Kaunas ghetto police).

LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 52 (Correspondence of Kaunas ghetto work brigades).

LCVA R-973, ap. 3, b. 52 (Work area of the Kaunas ghetto).

LCVA R-973, ap. 2, b. 145 (Interrogation logs of the head of the investigative section, ghetto police of Kaunas, May 1942–July 1943).

Literature

Balberyszki, Mendel (1967) Shtarker fun eisn [Stronger than iron]. Tel Aviv: Hamenora (Yiddish).

Bubnys, Arūnas (2014a) The Kaunas Ghetto. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, 2014.

Bubnys, Arūnas (2014b) The Šiauliai Ghetto. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, 2014.

Dieckmann, Christoph and Babette Quinkert, eds (2009) Im Ghetto 1939–1945. Neue Forschungen zu Alltag und Umfeld [In the Ghetto 1939–1945. New research on everyday life and the environment]. Göttingen: Wallstein.

Dworzecki, Mark Meir (1948) Yerusholayim D’Lita in Kamf und Umkum [Jerusalem of Lithuania in fight and extinction], Paris: Union Populaire.

Eilati, Shalom (2008) Crossing the River. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Faitelson, Alex (1998) Im jüdischen Widerstand [In the Jewish resistance]. Baden-Baden: Elster.

Imke Hansen, Katrin Steffen and Joachim Tauber (2013) Lebenswelt Ghetto. Alltag und soziales Umfeld während der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung [The Ghetto world, daily life and the social environment during Nazi persecution]. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz.

Levin, Dov and Zive A Brown (2014) The Story of an Underground. Jerusalem and New York, NY: Gefen Publishing House. Low, Andrea, Doris L. Bergen and Anna Hajkova (2014) Alltag im Holocaust. Leben im Großdeutschen Reich 1941–1944 [Daily life during the Holocaust. Life in the German Reich 1941–1945]. Munich: De Gruyter/Oldenbourg. Low, Andrea (2006) Juden im Ghetto Litzmannstadt. Lebensbedingungen, Selbstwahrnehmung, Verhalten [Jews in the Łódź ghetto. Living conditions, introspection and behaviour]. Göttingen: Wallstein. Feldshtein, Tzemach (1997) ‘At this Moment. Dr. Tzemach Feldshtein’s Editorials in the Vilna Ghetto, 1942–1943’, Yivo-Bleter, New Series, vol. III, 114–205 (Yiddish). Gar, Yozif (1948) Umkum fun der jidische Kovne [Untergang des jüdischen Kaunas] [The demise of Jewish Kaunas]. Munich: Rubinstein (Yiddish). Kruk, Herman (2002) The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps 1939–1944, ed. and intro. Benjamin Harshav. New Haven and London: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Sutzkever, Abraham (2009) Wilner Getto 1941–1944 [The Vilnius ghetto 1941–1944]. Zurich: Ammann. Tauber, Joachim (2015) Arbeit als Hoffnung. Jüdische Ghettos in Litauen 1941–1944 [Work as hope. Jewish ghettos in Lithuania 1944–1944]. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

This article has been published in the fifth issue of Remembrance and Solidarity Studies dedicated to the memory of Holocaust/Shoah.

>> Click here to see the R&S Studies site