„Rok 1989 – Jesień Ludów w krajach Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej – fundamentalnie zmienił oblicze kontynentu. Jednakże w naszej świadomości jesień symbolizuje raczej koniec pewnej epoki niż początek nowej. Jesień Ludów oznacza upadek komunistycznego systemu w sferze wpływów Związku Radzieckiego. To rozpad porządku jałtańskiego, koniec dwubiegunowej konfrontacji pomiędzy Wschodem a Zachodem. Rozpadł się dotychczasowy porządek świata.”[1] 1989 rok oznacza również koniec „krótkiego” XX wieku, który rozpoczął się dramatycznie od rewolucji październikowej w 1917 roku.

Pytanie, dlaczego komunizm upadł, skłania do determinizmu retrospektywnego, tym bardziej że niewielu obserwatorów przewidziało moment i sposób, w jaki dojdzie do upadku komunizmu. Być może pytanie to należałoby sprecyzować w odniesieniu do ponad 70-letniego trwania komunizmu. Dlaczego komunizm nie trwał dłużej? Odpowiedzi na to pytanie nie można ani po prostu pominąć, ani też w całości uogólnić, gdyż pod uwagę należy wziąć czynniki zewnętrzne, a przede wszystkim różne uwarunkowania wewnętrzne, które w 1989 roku doprowadziły do upadku systemu komunistycznego w krajach Europy Wschodniej.

„6 czerwca 1989 roku Michaił Gorbaczow przemawiał w Strasburgu przed Radą Europy i poinformował swoich słuchaczy, że Związek Radziecki nie będzie stał na drodze reform w Europie Wschodniej. Następnego dnia zapewnił na konferencji państw Układu Warszawskiego w Bukareszcie, że każde państwo socjalistyczne ma prawo podążać swoją drogą bez ingerencji zewnętrznej.”[2] Zapowiadając, że nie będzie interweniował, odebrał przywódcom rzekomych państw braterskich jedyną podstawę ich politycznego legitymizmu, a mianowicie zapewnienie, nierzadko groźbę, interwencji militarnej ze strony Moskwy. Bez tego rodzaju zapewnienia reżimy poszczególnych krajów zostały politycznie osłabione. Po tym jak centrum imperium oświadczyło publicznie, że nie będzie, nie chce się kurczowo trzymać rubieży pozostających w sferze swoich wpływów, co na całym świecie przyjęto z uznaniem, kwestią – mniej lub bardziej przewidywalnego – czasu pozostało tylko, kiedy poddadzą się namiestnicy imperium w Warszawie, Budapeszcie, Berlinie Wschodnim, Pradze i Bukareszcie.[3]

Otwartą sprawą pozostało oczywiście, jak i w jakim kierunku nastąpi upadek komunizmu w tych państwach. Otwartą sprawą było również to, czy następcy Jaruzelskiego, Honeckera, Jakeša, Ceauşescu i Kadara posłużą się instrumentami władzy, którymi bez wątpienia jeszcze dysponowali. Tego, że nie była to nierealna opcja, dowodzi brutalne zachowanie policji i organów służby bezpieczeństwa mające miejsce w tle oficjalnych uroczystości z okazji jubileuszu 40-lecia istnienia NRD w dniu 7 października 1989, a także 17 listopada 1989 w Czechosłowacji. W Bukareszcie, po ucieczce Ceauşescu z dachu budynku partii w dniu 22 grudnia 1989, żołnierze nowo powstałego „Frontu Ocalenia Narodowego” (FSN)[4] prowadzili kilkudniowe potyczki z jednostkami Securitate. To ci ostatni, obawiając się utraty władzy i ujawnienia popełnionych przez nich zbrodni, postawili na przemoc. Sam Ceauşescu został stracony (przez swoich byłych protegowanych) w pośpiechu już w pierwszy dzień Bożego Narodzenia.[5]

O tym, jakie skutki mógł mieć scenariusz zdarzeń z użyciem siły, mieszkańcy Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej mogli się przekonać 4 czerwca 1989 roku – w dniu, w którym przywódcy komunistycznych Chin kazali strzelać do pokojowo nastawionych demonstrantów na Placu Niebiańskiego Spokoju. Dokładnie w tym samym dniu, kiedy w Polsce odbywały się pierwsze półwolne wybory. Gratulując przywódcom Chin stłumienia demonstracji, Egon Krenz jako członek biura politycznego zdyskredytował się moralnie, jeszcze zanim 17 października 1989 objął stanowisko sekretarza generalnego SED po Honeckerze. Już po dwóch miesiącach na nadzwyczajnym zjeździe partii SED bądź PDS[6] został odwołany z pełnionej funkcji.

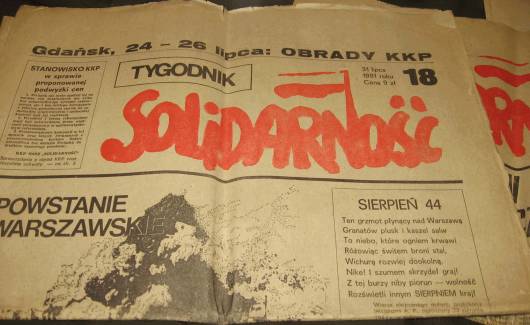

Na europejskiej scenie przywódcy z roku 1989 świadomie unikali sięgania po argument siły między innymi ze względu na odstraszający przykład masakry z Placu Niebiańskiego Spokoju. Nie tylko polska rewolucja rozpoczęta w 1980 roku przez Solidarność, która zakończyła się w 1989 roku, przyjęła tego rodzaju samoograniczenie. Przez dziesiątki lat władzy reżimy komunistyczne, stosujące groźby i siłę, zaprzepaściły kredyt zaufania. Mimo wszelkiej posiadanej broni niejako w sposób wymuszony nauczyły swoich obywateli, jak bardzo nieodpowiednie jest stosowanie siły.

Chociaż w 1989 roku komunistyczne partie w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej posiadały jeszcze instrumenty władzy, to brakowało im silnego przywództwa. „Tylko taka władza, która nie bała się rozlewu krwi, i to dużej ilości krwi, mogłaby sięgnąć po te środki. Komuniści nie zachowywali się już tak, jak mieli to w zwyczaju, gdy pojawiała się »kwestia władzy«, choć chińska partia komunistyczna dopiero co zademonstrowała, jak to się robi.

Zmieniło się coś, co miało decydujące znaczenie: na dole zniknęła obawa, a na górze odwaga. Na dole rosło zaufanie do samych siebie, a na górze ono znikało. Im bardziej dół rósł w siłę, tym bardziej zmniejszała się ona na górze.”[7] Osiem lat wcześniej polskie elity władzy pokazały, na co je stać, wprowadzając stan wojenny, gwałtownie zatrzymując rozwój podmiotowości polskiego społeczeństwa, był to krok, o który – zarówno na płaszczyźnie politycznej, jak i militarnej – upominali się sprawujący władzę w Moskwie, Berlinie Wschodnim i Pradze (w mniejszym stopniu w Budapeszcie), by w końcu z radością posłużyć się nim do celów propagandowych.

Społeczeństwa tych krajów w znacznym stopniu solidaryzowały się z sytuacją Polaków, czuły przecież, że władza komunistyczna była zachwiana jak nigdy dotąd. Jednakże nie chciały lub nie mogły one okazać otwartej sympatii dla odwagi Polaków. W 1989 roku żadne z kierownictw partii (z wyjątkiem rumuńskiej, a tam była to raczej Securitate) nie odważyło się zaryzykować użycia siły. W Berlinie Wschodnim i w Pradze wyczuwano, że nie ma co liczyć na pomoc Moskwy. Przed 1989 partie komunistyczne w Warszawie i w Budapeszcie powoli uwalniały się od paradygmatu leninowskiej partii kadrowej i szukały ratunku w podejmowaniu połowicznych reform gospodarczych, w zapewnieniu ograniczonej wolności kulturalnej oraz w narodowej polityce symboli. W 1989 roku kierownictwa wszystkich czterech partii komunistycznych nie były już pewne swoich fundamentów partyjnych, swojego przesłania, a przede wszystkim siebie samych, by móc cokolwiek przeciwstawić rewolucyjnym zapędom obywateli swoich państw.

„Niechęć do siły to wszystko, co łączyło wielu rewolucjonistów z 1989 roku. Była to nader mieszana grupa (...). Nierzadko należeli do nich reformatorzy komunistyczni, socjaldemokraci, liberalni intelektualiści, nacjonaliści, osoby będące zwolennikami gospodarki rynkowej, działacze katoliccy, przedstawiciele związków zawodowych, pacyfiści, konserwatywni trockiści i wielu innych. Ta wielka różnorodność stanowiła część ich siły: utworzyli oni de facto nieformalną grupę składającą się z organizacji obywatelskich i politycznych, która stanowiła zagrożenie dla państwa opartego na systemie jednopartyjnym.”[8]

Zaawansowana strukturalnie i typowa ideologicznie homogeniczność krajów pozostających pod wpływem Związku Radzieckiego sprawiła, że zagrożenie lub upadek kierownictwa partii komunistycznej w jednym z tych krajów nieuchronnie osłabiały legitymizm innego kierownictwa. „Wiarygodność opierała się częściowo na twierdzeniu (...), że jest się logicznym produktem idei postępu historycznego.”[9] To twierdzenie w dobitny sposób zostało zachwiane, np. przez zwykłe istnienie dziewięciomilionowego ruchu „Solidarność”, co z jednej strony w kierownictwie NRD wywołało przerażenie, z drugiej zaś w ČSSR i na Węgrzech budziło niepewność.

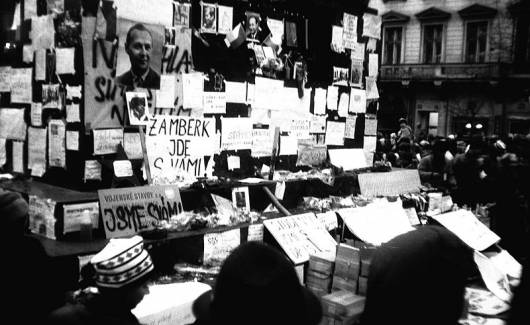

Zniszczenie legitymizmu władzy rządzącej przez skumulowaną siłę masy to chyba istotna cecha rewolucji. „Było tak w 1848 i w 1919 roku. Novum rewolucji z 1989 roku to tempo tego procesu. Myśl tę odzwierciedla często cytowane zdanie: „W Polsce trwało to dziesięć lat, na Węgrzech dziesięć miesięcy, w NRD dziesięć tygodni, a w Czechosłowacji dziesięć dni”.[10] „Jeszcze w październiku 1989 roku przewodniczący partii okresu przejściowego Imre Pozsgay na Węgrzech lub Egon Krenz w NRD wyobrażali sobie, że będą w stanie kontrolować i kierować swoim modelem pierestrojki.”[11] Były to zamiary, które dziesięć miesięcy później okazały się iluzją.

Do przyspieszenia i rozwoju sytuacji, nie dającej się już powstrzymać, przyczyniły się media. Przede wszystkim Węgrzy i Czesi mogli co wieczór oglądać w wiadomościach telewizyjnych swoją własną rewolucję. Wschodnich Niemców, którzy każdego wieczoru byli zajęci oglądaniem zachodniej telewizji, nie nachodziła już chęć emigrowania, lecz czuli, że są podmiotem historycznych zmian. Od Schwerina po Szeged telewizja stanowiła część wychowania politycznego, głosząc proste, ale wymowne przesłanie: „Są pozbawieni władzy” oraz „My tego dokonaliśmy”. Niezależnie od tego, czy są to zdjęcia z ekshumacji i przeniesienia szczątków Imre Nagiego z 16 czerwca 1989, z poniedziałkowych manifestacji w Lipsku z października 1989 czy manifestujących studentów praskich z 17 listopada 1989 roku. To wzniosłe uczucie odzyskania własnej godności, którą wywalczyli i entuzjastycznie świętowali Polacy w 1980 roku, stało się teraz zrozumiałe również dla Czechów, Słowaków, Węgrów i w szczególny sposób dla wschodnich Niemców.

W przeciągu kilku dni władze komunistyczne straciły to, czego pilnowały tak pieczołowicie, stosując ciągłe restrykcje, a mianowicie monopol informacyjny. Na zawsze minęła obawa osamotnienia, która kładła się cieniem na działalności opozycyjnej przede wszystkim w NRD i Czechosłowacji, siejąc niepewność i zniechęcenie.

Jednakże w Polsce transformacja, którą przyniósł rok 1989, nie zamieniła kraju w miejsce pamięci przepełnione kipiącą radością i emocjonalnym wzruszeniem. Podczas obrad Okrągłego Stołu, toczących się pomiędzy znaczną częścią opozycji a elitami władzy, nie chodziło już o to, by ci ostatni oddali lub podzielili się władzą, lecz przede wszystkim o to, w jaki sposób ma się to odbyć. Rzeczowość i umiejętność prowadzenia negocjacji były bardziej potrzebne niż rewolucyjny zapał. Większość polskiego społeczeństwa nie ukrywała wprawdzie swojej sympatii dla przedstawicieli opozycji, dla „Komitetu Obywatelskiego Solidarność”, ale już po zalegalizowaniu Solidarności nie udało się jednak osiągnąć mobilizacji społecznej i wzbudzić uczucia wolności z jesieni 1980 roku. W 1989 roku przeważało życzenie, by rząd utworzony w wyniku rozmów przy Okrągłym Stole i wyborów z czerwca 1989 roku możliwie jak najszybciej zapanował nad katastrofalną sytuacją gospodarczą i hiperinflacją.[12]

Okrągły Stół jako typowy polski „wynalazek” spotkał się z żywym zainteresowaniem wśród grup opozycyjnych w NRD i na Węgrzech, postrzegano go jako przykład godny naśladowania i stosowano w praktyce. To fakt, na który w Polsce w znacznej mierze przestano po prostu zwracać uwagę.[13] 10 listopada 1989 roku Lothar de Maizière, mówiąc: „ważne jest, abyśmy każdemu człowiekowi zwrócili poczucie wyjątkowości jako istocie stworzonej na podobieństwo Boga, jego subiektywizm oraz dojrzałość”[14], jako protestant nawiązywał wyraźnie do doświadczeń i postulatów Solidarności.

W Polsce istniały i nadal istnieją kontrowersje wokół oceny „Okrągłego Stołu”, które wpisują się zarówno w życie polityczne, jak i forum publicystyczne, choć pewną rolę grają również w dyskursie naukowym.[15] W debacie publicznej w ostatnich 20 latach zajmowane pozycje i stanowiska uległy nierzadko zmianie. Wcześniejsi zwolennicy Okrągłego Stołu stali się w międzyczasie jego krytykami. Ale i ówcześni krytycy nierzadko postrzegają Okrągły Stół w łagodniejszym świetle jako pozytywny impuls do zmiany systemu.[16]

Przede wszystkim przedstawiciele tego odłamu dawnej Solidarności, którzy w 1989 roku nie uczestniczyli w obradach Okrągłego Stołu, ale również emigracyjna „Kultura” zarzucała, że zawarto wówczas niedopuszczalną elitarną ugodę z przeciwnikiem.[17] Te słowa krytyki pojawiają się nieustannie i w gwałtowny sposób w odniesieniu do odnowionej III Rzeczpospolitej. Argument, który jest wysuwany przeciwko Okrągłemu Stołowi, to twierdzenie, że nie stanowi on żadnej jednoznacznej cezury, oddzielającej epokę komunizmu od ery demokracji. Poza tym miał on utrudnić moralne rozliczenie się z komunizmem. Ale przede wszystkim podkreśla się to, że dzięki niemu przedstawicielom starej nomenklatury umożliwiono uczestniczenie w procesie prywatyzacji. W wielu punktach krytyka ta jest bez wątpienia zasadna. Wątpliwa jest natomiast teza krytyków „Okrągłego Stołu”, że komunizm w Polsce był już na tyle osłabiony, że system tak czy siak załamałby się wkrótce, gdyby tylko masowy ruch opozycji zadał mu ostatni cios.[18] Te retrospektywne rozważania opierają się na fakcie, że Polska była pierwszym krajem posiadającym rząd, w którym przewagę mieli przedstawiciele zakazanej wcześniej opozycji, ale była też ostatnim krajem postkomunistycznym, w którym odbyły się w pełni wolne wybory. W tej retrospektywnej ocenie nie doceniono natomiast w dostatecznym stopniu sytuacji w polityce zagranicznej oraz niepewności w odniesieniu do potencjalnych reakcji ze strony Związku Radzieckiego. [19]

Upadek muru berlińskiego, o którym informację 9 listopada Günter Schabowski na konferencji prasowej przekazał do publicznej wiadomości niemalże przypadkowo, wywołał – pod względem emocjonalnym – niesamowicie szczęśliwą noc, która w zbiorowej pamięci większości Niemców znalazła swoje trwałe i należyte miejsce. W ankiecie przeprowadzonej w 2004 roku wśród Polaków i Niemców, która dotyczyła najważniejszego wydarzenia historycznego w ostatnim stuleciu, Niemcy opowiedzieli się za zjednoczeniem, a Polacy wskazywali na wybuch II wojny światowej.[20]

Ta odmienna ocena znajduje odzwierciedlenie nie tylko w uwadze historyczno-politycznej, która w Polsce jest poświęcana wydarzeniu z 1939 roku, a w Niemczech z 1989 roku. W Niemczech obserwuje się prawdziwą powódź wspomnień związanych z rokiem 1989 – towarzyszy jej debata na temat nadrzędnego charakteru wykładni historycznej: przedmiotem dyskusji jest zestawienie haseł „przełom” i „pokojowa rewolucja”. Można odnieść wrażenie, że w 2009 roku, w którym obchodzi się jubileusz upadku muru berlińskiego, żadne media nie chcą pozostać w tyle. Już na wiosnę 2009 roku branża wydawnicza wytyczyła temat przewodni tego roku jubileuszowego i na rynku pojawiło się wiele publikacji. Od początku lata rozgłośnie niemieckie oraz gazety informowały o roku 1989, poświęcając temu zagadnieniu zarówno małe „kroniki”, jak i większe rozprawy. Należy wspomnieć także wiele inicjatyw i stowarzyszeń, szczególnie we wschodniej części Republiki, których działalność – i często też powstanie – wiąże się z rewolucyjną jesienią roku 1989. Na berlińskim Alexanderplatz od maja 2009 można było oglądać wystawę zorganizowaną pod gołym niebem na temat „Pokojowej Rewolucji 1989/90”. Obok wystawy oznaczono w Berlinie na stałe miejsca pamięci i punkty informacyjne, które wskazywały na ważne historyczne miejsca pokojowej rewolucji, tak aby można było poznawać historię tam, gdzie się ona toczyła i żeby utrwalić ten szczególny moment historii wolności w powszechnej niemieckiej świadomości.[21]

Tego rodzaju działania mające na celu krzewienie pamięci o przeszłości śledzi się w Polsce z większą uwagą, aniżeli się je pomija. Niekiedy można odnieść w Polsce nieprzyjemne wrażenie, jakoby Niemcy, poprzez podkreślanie upadku muru i zasług Gorbaczowa, jak również otwarcia granic na Węgrzech, mieli pomniejszać wkład Polski w rozwój wydarzeń Jesieni Ludów z 1989 roku.[22]

Mur berliński to nie tylko symbol końca 28-letniego betonowego podziału Niemiec, lecz również miejsce pamięci o końcu podziału Europy. Mur berliński i podział Niemiec stanowiły geopolityczną blokadę Europy. Dopiero jego zburzenie umożliwiło nawiązanie kontaktów z Zachodem, w tym również przez Polskę. Historyczna rywalizacja na płaszczyźnie wspomnień nie ma w tym miejscu nie tylko żadnego sensu, lecz niemalże prowadzi do zafałszowania historii. Stocznia Gdańska i mur berliński były komunikacyjnymi naczyniami powiązanymi. Bez stoczni nie doszłoby do upadku muru, ale bez upadku muru i Zjednoczenia Niemiec Polska i Węgry z trudem wyzwoliłyby się z objęć sowieckiego brata. Polska opozycja z lat 70. i 80. dostrzegła ten fakt jak żadna inna – ku niezadowoleniu wielu polityków, również tych z Zachodu.[23]

Rok 1989 – jako czas pamięci – nie zostałby dostatecznie opisany, gdyby pominięto Zjednoczenie Niemiec oraz utarty międzynarodowy sposób postrzegania i stereotypy. W rewolucyjnym roku 1989 pojawiły się one w ogromnej ilości i zostały poddane w wątpliwość, nie wzbudzając tym samym wielkiej radości niektórych europejskich rządów. Co się stało? Do 1989 roku w Europie Zachodniej istniał ogólny konsensus, że kwestia niemiecka będzie przedmiotem dyskusji wtedy, gdy zostaną spełnione określone przesłanki polityczne, tzn. gdy zostanie stworzony europejski ład pokojowy. Rzeczywistość wyglądała w gruncie rzeczy zupełnie inaczej. Upadek muru oraz połączenie się Niemców ze Wschodu i Zachodu był, przynajmniej w pierwszych miesiącach, aktem wyzwalającym i emocjonalnym, który wywracał do góry nogami założenia polityki zagranicznej oraz jej priorytety. Zjednoczenie Niemiec stało się nagle możliwe i to zanim Europa porozumiała się w tej sprawie. „Cztery siły ponoszące odpowiedzialność za Niemcy w aspekcie swojej wolności działania widziały, że są ograniczone w dwojaki sposób: nie mogły dalej utrzymać podziału Europy, gdyż zjednoczenie dokonywało się w rzeczywistości od dołu; a Republika Federalna Niemiec – wyznaczająca sobie zjednoczenie za cel państwa – urosła do rangi średniej wielkości mocarstwa, którego interesy należało respektować.”[24]

Francja i Wielka Brytania były poważnie zaniepokojone tą przypuszczalnie niekontrolowaną siłą osiemdziesięciomilionowego narodu, zważywszy na to, że Margaret Thatcher tak czy owak nie brała na poważnie wspólnego porozumienia europejskiego. W swoich wspomnieniach Thatcher – jako zdecydowana antykomunistka – przyznaje, że nie przystoi, by „wschodni Niemcy nadal mieli żyć pod rządami komunistów”, jednakże w innym miejscu swoich wspomnień podejrzewa ich o „polityczną niedojrzałość” oraz o tendencje do „neofaszyzmu”, jakby później chciała usprawiedliwić swoje błędne stanowisko w kwestii niemieckiej.[25]

Dla świeżo wybranego rządu Tadeusza Mazowieckiego Zjednoczenie Niemiec niosło szansę na ostrożne zastąpienie starych zobowiązań zaciągniętych w Układzie Warszawskim przez nawiązanie niezależnych i nowych, partnerskich stosunków z Zachodem. Stanowisko Mazowieckiego wynikało z tradycji części polskiej opozycji demokratycznej, która – jako PPN[26] – opowiedziała się programowo za Zjednoczeniem Niemiec już w 1978 roku.[27]

Sympatia polskiego rządu dla demokratycznej Republiki Federalnej została wystawiona na ciężką próbę w momencie, gdy Helmut Kohl 7 grudnia 1989 roku przedstawił swój dziesięciopunktowy plan zjednoczenia Niemiec i pominął w nim kwestię granicy na Odrze i Nysie. W tej sytuacji polski rząd, a właściwie minister spraw zagranicznych Krzysztof Skubiszewski, wyraził swoje szczególne zaniepokojenie, bo przecież Układ z 1970 roku obowiązywał tylko starą Republikę Federalną Niemiec, a nie zjednoczone Niemcy. Lech Wałęsa ostrzegał: „Jeżeli ktoś się odważy ponownie podzielić Europę, wtedy Polska będzie musiała sobie przypomnieć Piłsudskiego i być gotowa na konfrontację siły”.[28]

Te obawy nie robiły jednak wrażenia na USA. Prezydent George Bush senior i jego minister spraw zagranicznych Baker dostrzegli wcześniej niż inni, że zjednoczenia Niemiec nie można było powstrzymać. Jak trafnie określił to Peter Bender, Stany Zjednoczone są dostatecznie silne i znajdują się w bezpiecznej odległości, przez co mogą sobie pozwolić na zjednoczone Niemcy.[29] Zjednoczenie Niemiec poprzez rozwiązanie NRD zmusiłoby dodatkowo Związek Radziecki do ostatecznego wycofania się z Niemiec Wschodnich, a całkiem prawdopodobne, że również z całej Europy Środkowej. Zjednoczenie Niemiec oznaczało dla Ameryki to, co w końcu osiągnęła, o co przez czterdzieści lat walczyła ze Związkiem Radzieckim, a mianowicie – zwycięstwo w Zimnej Wojnie.[30]

Zgoda Gorbaczowa na połączenie obu państw niemieckich i członkostwo Niemiec w NATO wynikała w zasadzie z uzmysłowienia sobie, że trzeba zrezygnować z NRD i Europy Środkowej, by móc się skoncentrować na uzdrowieniu Związku Radzieckiego, i w tym celu pozyskać pomoc Zachodu. Nawet jeżeli Gorbaczow przeliczył się co do swoich krytyków w kraju, to jego odwaga i dokonania strategiczne są nieocenione, i z pewnością na zawsze zapisze się on w podręcznikach historii.

Do dzisiaj epokowy przełom Jesieni Ludów nie stał się mitem założycielskim – ani dla zjednoczonych Niemiec, ani dla III Rzeczpospolitej, ani dla zjednoczonej Europy. Bo jakby inaczej niemiecki kanclerz mógł wpaść na pomysł ponownego zniesienia Dnia Jedności Niemieckiej? Jürgen Habermas określił kiedyś procesy zachodzące w 1989 roku jako „doganiającą rewolucję”, a więc jako próbę dogonienia rozwoju cywilizacyjnego i konstytucyjnego, który na Zachodzie już dawno się zakończył. W przeciwnym razie ten proces doganiania nie będzie mógł wnieść nic nowego do historyczno-politycznej tożsamości narodów.[31]

Ten instytucjonalny punkt widzenia nie docenia często w dostatecznym stopniu innego rodzaju wspomnień, doświadczeń i procesu socjalizacji w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej, ale i pierwotnych emancypacyjnych dokonań zwłaszcza w odniesieniu do roku 1989.

„Rewolucje mające miejsce na jesieni 1989 roku nie pojawiły się ot tak, nawet jeśli niektórym może się dziś tak wydawać. Poprzedzały je inne wydarzenia – masowe protesty, powstania i strajki, te, które się nie powiodły, jak w przypadku 17 czerwca czy powstania węgierskiego z 1956 roku, jak i te, które się zakończyły się powodzeniem, jak ruch Solidarność. Są to również niezliczone świadectwa pojedynczych osób i małych grup – świadectwa wiary we własne możliwości i wymuszonej wolności sumienia oraz wywalczonych praw człowieka i obywatela, jak również dokonań społecznej samoorganizacji z dala od struktur władzy państwa partyjnego”.[32] Ludwig Mehlhorn nazwał ten proces „transformacją przez opór” zamiast „zmiany przez zbliżenie”.[33]

Na krótko przed rewolucyjnym rokiem 1989 Jerzy Turowicz, długoletni redaktor naczelny krakowskiego „Tygodnika Powszechnego”, stwierdził w swego rodzaju wspomnieniach: „Jeżeli jednak w pewnych sprawach nie dorastamy do Zachodu, to mamy za sobą szczególne doświadczenie historyczne, a myślę tu o naszej najnowszej historii. To doświadczenie umożliwia nam głębsze zrozumienie współczesnego świata i jego zagrożeń, daje nam pewną mądrość życiową, której Zachód nie posiada. Dlatego są sprawy, w których z ludźmi z Zachodu czasem trudno nam się dogadać.”[34]

Jeżeli kontynent nawet uporał się politycznie z porządkiem jałtańskim, tj. podziałem na dyktatorski Wschód i demokratyczny Zachód, stanowiący konsekwencję II wojny światowej, to kultury pamięci w Europie Wschodniej i Zachodniej funkcjonują nadal obok siebie, nierzadko przeciwko sobie, jakby za żelazną kurtyną ironia losu utkwiła w świadomości mieszkańców Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej głębiej, aniżeli uważa się to za możliwe w stolicach krajów Europy Zachodniej. Skutkuje to tym, że pamięć komunikacyjną na Wschodzie i Zachodzie 17 lat po rewolucji z 1989 roku wypełniają wspomnienia w małym stopniu zgodne ze sobą, a wzajemne postrzeganie – nie tylko na Zachodzie – odsłania brak zrozumienia i wyobraźni.[35]

W opinii Ralfa Dahrendorfa rok „1989” – w „niemieckiej świadomości intelektualnej” – „nie stanowi momentu przełomowego, jak ma to miejsce w pozostałej części Europy, a na pewno nie jest momentem przerwy na głęboki oddech czy też triumfem otwartego społeczeństwa”.[36] Dystansując się od tego stanowiska, Dahrendorf traktuje rok „1989” nie tylko jako cezurę o wymiarze globalnym, uważa, że rok „1989” może być dla Europy mitem założycielskim w takim stopniu, jak „czysta nauka wypływająca z dokonań rewolucji francuskiej – liberté, égalité, fraternité – (...) nadal stanowi przedmiot dyskusji politycznej”[37].

Retrospektywne spojrzenie na działania kobiet i mężczyzn z Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej w 1989 roku jest w szczególny sposób odpowiednie, by zostać uznane w historii wolności jako przykład działania skłaniającego do przemyśleń nad urzeczywistnianiem się społeczeństwa obywatelskiego w Europie. Wolfgang Eichwede określa ich mianem „dzieci oświecenia”, gdyż dzięki swojej odwadze, zaufaniu do opinii publicznej oraz sile swojego przykładu wysiały ziarno społeczeństwa obywatelskiego, które wzeszło w 1989 roku.[38]

Obok innych wydarzeń rok „1989” – jako trwały czas pamięci – musi zakorzenić się w europejskiej kulturze pamięci. Rok „1989” to czas rewolucyjnego ruchu narodów w walce o demokratyczne państwo prawa. Celem tego ruchu było lepsze życie bez nadzoru oraz pokonanie granic i dowiodło ono, że zawsze i wszędzie opłaca się stawać po stronie godności i wolności jednostki, i bronić tych wartości. Rok 1989 to europejski czas pamięci, gdyż dopiero on umożliwił powstanie Europy w jej obecnym kształcie.[39]

dr Burkhard Olschowsky (ur. 1969 w Berlinie) studiował historię i historię Europy wschodniej w Getyndze, Warszawie i Berlinie. W 2002 r. obronił doktorat na Uniwersytecie Humboldta w Berlinie. W latach 2003-2005 pracował jako wykładowca kontraktowy z dziedziny historii współczesnej i polityki na Uniwersytecie Humboldta. W latach 2004-2005 pracował w Federalnym Ministerstwie Transportu, Budownictwa i Mieszkalnictwa. Od maja 2005 pracownik naukowy w Federalnym Instytucie ds. Kultury i Historii Niemców w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej. Od 2010 pracownik naukowy w Sekretariacie Europejskiej Sieci Pamięć i Solidarność.

[1] L. Mehlhorn, Das Jahr 1989 und das fortdauernde Problem der Delegitimierung des Kommunismus [w:] I. Syrunt, M. Zybura (red.) Die „Wende”. Die politische Wende 1989/90 im öffentlichen Diskurs Mittel- und Osteuropas, Hamburg 2007, s. 36 (36–41).

[2] T. Judt, Geschichte Europas von 1945 bis zur Gegenwart, München und Wien 2005, s. 727.

[3] Ibidem, s. 728.

[4] FSN – Frontul Salvǎrii Naţionale.

[5] G. Dalos, Der Vorgang geht auf. Das Ende der Dikataturen in Osteuropa, München 2009, s. 232 i następne.

[6] SED – Niemiecka Socjalistyczna Partia Jedności, PDS – Partia Demokratycznego Socjalizmu.

[7] P. Bender, Deutschlands Wiederkehr. Eine ungeteilte Nachkriegsgeschichte 1945–1990, s. 229 i następne.

[8] T. Judt, Geschichte Europas von 1945 bis zur Gegenwart, München und Wien 2005, s. 724.

[9] Ibidem, s. 722

[10] T. G. Ash, Ein Jahrhundert wird abgewählt. Aus den Zentren Mitteleuropas 1980-1990, München, Wien 1990, s. 401.

[11] T. Judt, von 1945 bis zur Gegenwart, München und Wien 2005, s. 723.

[12] J. Skórzyński, Rewolucja okrągłego stołu, Kraków 2009, s. 141–145, 161–169.

[13] A. Schmidt-Schweitzer, Politische Geschichte Ungarns von 1985 bis 2002, München 2007, s. 98; D. Trutkowski, Der Sturz der Diktatur. Opposition in Polen und der DDR 1988/89, Berlin 2007, s. 96 i następne.

[14] Oświadczenie nowego przewodniczącego CDU w NRD Lothara des Maizièrego, 10.11.1989 [w:] G. Rein, Die protestantische Revolution 1987–1990, Berlin 1990, s. 288.

[15] A. Dudek, Polski rok 1989 i spory wokół jego postrzegania (artykuł w publikacji o „miejscach pamięci w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej”, która wkrótce zostanie wydana).

[16] Lech Kaczyński o Okrągłym Stole: Duży stół, dużo alkoholu, Dziennik 4.2.2009; Borusewicz zaczął pozytywnie oceniać Okrągły Stół, PAP 3.2.2009; A. Hall, Okrągły Stół – ani rewolucyjny zryw, ani kapitulacja, Dziennik 30.1.2009.

[17] Jan Olszewski w rozmowie z Antonim Macierewiczem [w:] Głos nr. 54 (1989); „Solidarność Walcząca”: To kolejny wybieg władzy, Wywiad z Kornelem Morawieckim [w] Głos Solidarności nr.10 (1988); K. Gawlikowski, O polskim „kompromisie historycznym”, [w:] Kultura, nr. 3/498 (1989), s. (3-7); Z. Romaszewski, Minimalizm radykalny [w:] Kultura, nr.3/498, s. 11 (9-28).

[18] B. Wildstein, Elity się porozumiewały, tłum bił brawo [w:] Rzeczpospolita 5.2.2009; R. A. Ziemkiewicz, Sterta bzdur o Okrągłym Stole [w:] Rzeczpospolita 11.2.2009; A. Hall, Okrągły Stół – ani rewolucyjny zryw, ani kapitulacja [w:] Dziennik 30.1.2009; P. Winczorek, Tadeusz Mazowiecki bez lukru [w:] Rzeczpospolita 17.9.2009.

[19] J. Holzer, Polen und Europa. Land, Geschichte, Identität, Bonn 2007, s. 96.

[20] Reprezentatywna ankieta czasopisma GEO Spezial (sierpień/wrzesień 2004), przedruk [w:] Dialog, nr 68 (2004), s. 5.

[21] <http://www.havemann-gesellschaft.de> <http://revolution89.de/?PID=static,Revolutionsstelen,00020-Aktuelles_de> (stan z dnia 2.3.2010).

[22] Niemcy pamiętają o „Solidarności”, Wywiad z Frank-Walterem Steinmeierem [w:] Rzeczpospolita 9.2.2009; Świat uczcił upadek muru [w:] Dziennik 10./11.11.2009.

[23] K. Rogaczewska, Niemcy w myśli politycznej polskiej opozycji w latach 1976–1989, Wrocław 1998, s. 130–138; B. Olschowsky, Einvernehmen und Konflikt. Das Verhältnis zwischen der Volksrepublik Polen und der DDR 1980–1989, Osnabrück 2005, s. 442, 447.

[24] P. Bender, Deutschlands Wiederkehr. Eine ungeteilte Nachkriegsgeschichte 1945–1990, s. 246.

[25] M. Thatcher, Downing Street No. 10. Die Erinnerungen, Düsseldorf 1993, s. 1097 i następne, 1126 i następne.

[26] PPN – Polskie Porozumienie Niepodległościowe.

[27] P. Zariczny, Das geteilte Deutschland in der oppostionellen Publizistik Polens anhand von ausgewählten Beispielen [w:] Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici, zeszyt 371 (2005), s. 113 (99–119).

[28] Gazeta Wyborcza, 8.12.1989.

[29] P. Bender, Deutschlands Wiederkehr. Eine ungeteilte Nachkriegsgeschichte 1945–1990, s. 248.

[30] R. G. Powers, Not Without Honor. The History of American Anti-Communism, New York 1995; M. E. Sarotte, 1989. The struggle to create Post-Cold War Europe, Princeton 2009, s. 65–87.

[31] J. Habermas, Die nachholende Revolution, Frankfurt/Main 1990, s. 179–188.

[32] L. Mehlhorn, Das Jahr 1989 und das fortdauernde Problem der Delegitimierung des Kommunismus [w:] I. Syrunt, M. Zybura (red.) Die „Wende”. Die politische Wende 1989/90 im öffentlichen Diskurs Mittel- und Osteuropas, Hamburg 2007, s. 39 i następne.

[33] Konferencja Kirchliche Versöhnungsinitiativen und deutsch-polnische Verständigung, Berlin-Schwanenwerder 4.-5.11.2005, <http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/tagungsberichte/id=972> (stan z 2.3.2010; artykuł obejmuje dwie konferencje).

[34] J. Żakowski, 3 ćwiartki wieku. Rozmowy z Jerzym Turowiczem, Kraków 1990, s. 127.

[35] Por. A. Paczkowski, Gedächtniswelten. Das „alte” und das „neue” Europa [w:] B. Kauffmann, B. Kerski (red.) Antisemitismus und Erinnerungskulturen im postkommunistischen Europa, Osnabrück 2006 (Puplikacje Deutsch-Polnischen Gesellschaft Bundesverband e. V. 10), s. 135–145.

[36] R. Dahrendorf, Der Wiederbeginn der Geschichte. Vom Fall der Mauer zum Krieg im Irak. Reden und Aufsätze, München 2004, s. 216.

[37] Ibidem, s. 213.

[38] W. Eichwede, Kinder der Aufklärung [w:] Kafka. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa 3 (2001), s. 8–13; B. Kerski, J. Giedroyc, Kultura und die Krise der europäischen Identität [w:] Ł. Galecki, B. Kerski (red.) Die polnische Emigration und Europa 1945–1990. Eine Bilanz des politischen Denkens und der Literatur Polens im Exil, Osnabrück 2000, s. 73–94, tu: s. 91 i następne.

[39] I. S. Kowalczuk, 1989 in Perspektive: Ralf Dahrendorfs Antiutopismus [w:] Merkur. Deutsche Zeitschrift für europäisches Denken 59, (2005) 1, nr. 669, s. 69 (65–69).