ABSTRACT

The present paper draws on the opinion that reality is only a construct. The relativistic theory of truth displaces the classical (Aristotelian) one. It notes the undepictability (of the world) and (actual) inexpressibility. On the basis of two relatively progressive works (Dorota Masłowska’s book “Wojna polsko-ruska pod flagą biało-czerwoną” [literal translation of the title: The Polish-Russki War Under the White-and-Red Flag; edited as “White and Red” in the UK and “Snow White and Russian Red” in the US], and Xawery Żuławski’s film “Wojna Polsko-Ruska/Polish-Russian War”], this paper confirms the traps of (artificial) limits of both thematization and division into academic disciplines and shows how contemporary art, writing about art included, tries to deal with them.

Instead of problematization – simultaneity and multi-layered structure, which try to be a counterpart, a representative but not an exponent (cf. the category of inexpressibility). A turn – of sonoristic provenance – from the civilizationally formed discourses towards the analysis of the tool itself (language and film language) as possibly the most non-abstract object of study.

The current paper takes as its starting point the question – already present in literary studies – about the purpose of the history of literature as an oppressive attempt to build, under the cover of objectivism, a dominating narration and hierarchy. The paper has been implemented for a monographic issue of a historical magazine; an issue devoted to economic crises. It poses also a preliminary question about the ontological possibility of isolating types of crises and remembering them in an agreed (objective) and subjective way; and also about the possibility of reflecting them in contemporary art, in comparison with works from earlier turning points in history.

I (Assumptions, methodology)

1

Memory may not exist.1

2

There is no history either (meaning that history is always “an untruth”, an interpretation. Always proclaimed in the interest of someone, either designedly or undesignedly. My history, your history, constitutively unobjective).2

3

And “category of truth”? Maybe such as was mentioned by Józef Tischner, professor of philosophy.3

4

Instead there “is” intederminability, changeability, fluidity, continuous reinterpretation, a process.4

5

So what might history, which does not (objectively) exist, be like? A story, a narrative. The latter notion appears most often in the context of objects of ART. A narrative is ARTIFICIAL. It is a point of view. An attempt to impose one’s own vision or one’s own mirage on the other participants who have decided to enter “the same” (or “an identical”) discourse. An attempt to impose one’s own language, to subordinate others to oneself, according to the folk wisdom expressed in the saying “bring down to your own level and wipe out with the force of your own argumentation”. It is oppression.

There is no unified history, there is only a struggle of multiple histories, a fight of narratives. And a fight of historical policies, which have even less in common with the unattainable ideal of objectivism. A permanent inability to agree, a battlefield. A battle in which individuals and collectivities take part.5

6

These are auxiliary categories, ones that make our existence easier: this is it and there’s nothing more to it.

7

This paper is a mirror, an individual act of reflection on a few intellectual currents, rather than an original contribution.6

8

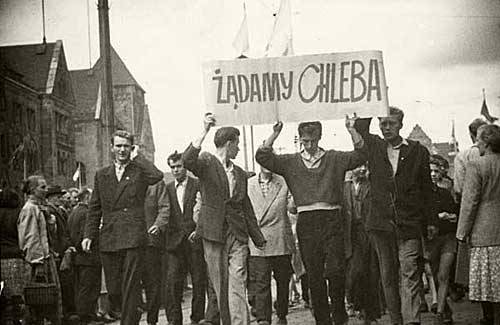

Unfortunately – as we see nowadays – some try to find a remedy for the crisis, or at least to conceal its causes, by sparking a war.7

9

Waiting for a narration of the turning point was crowned by success, but this success took an unexpected form. Its identification took place too late and is still rejected by many.

10

After the political turning point of 1989, which was partly evoked by and partly caused an economic crisis, there rose an expectation of an overview, a vast literary panorama. An expectation that art would offer a reflection of what was taking place in real life. A reflection or a distortion, if you will (e.g. through the category of grotesque like Trans-Atlantyk by Witold Gombrowicz.8).

But in the meantime a complete change of circumstances (rebus sic stantibus) took place in Poland (in the world it began at least in the 1970s), and because of it the object of the expectations was inapplicable to what could be accepted as a proper answer.

Belatedly (later than it was expected) “narratives” (stories) appeared which were moderately consistent with the object of the expectations, but not meeting the expectations.

The object of these expectations, referring to the past and not to the future, is the longing for a great novel about a turning point, like War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy or The Doll by Boleslaw Prus (although it was written despite and beyond the expectations of its times and offered a new approach to the topic).

The expectations were quite high: to relate and to provide a diagnosis: somewhat predictable but surprising at the same time.

There appeared – too late – works of the same type (content) but not as great as The Doll, however they did not evoke such resonance. I will not mention them here because this paper is not a polemic (within literary studies as such – it does not aim to analyse and change the hierarchies, nor to study what constitutes a masterpiece etc.).

It seems that a desired narrative about a turning point in history should also be a turning point in the way of thinking.

Thus expectiation should be an open formula, and not a written content. The work which is to “meet the expectations” of the times, must also be a surprise.

11

According to some of those who had expected it, such a work appeared after a lengthy period of time, and it took even longer before it was recognized and qualified.

Whereas those to whom it seemed (a good word) to be addressed, did not have such an expectation at all.

12

Here we come to the first turning point in this presentation. On its account one must assume that

a) memory about economic crises (as well as narratives about them e.g. in historical research or in reportage) or reflection of economic crises (in art, partly also in reportage as a subjective choice, personal description and interpretation of facts) are possible;

b) memory about crises and reflection of crises were materialized;

c) in some aspects Snow White and Russian Red may be accepted as such a materialization (footnote later, it will be justified).

13

It is pointless to bandy around the aesthetics of novelty if a book is over ten years old. It was indeed a novelty as far as Polish literature is concerned. Its determinants were and still are widely available (not to say dominant) in world literature. Let us name and enumerate them:

a) escape from thematization;

b) pretextuality of the plot, polemics with its essence, essentiality and validity;

c) escape from ideology – everything happens in the language, through the language and for the language. A novel about the language which is self-reflexive, and non-referential. Reality (if it exists at all) cannot be described. One may also mention the related category of inexpressibility.

Only words are “objectively” available from start to finish; if anything is certain at all, it is words. But not their meaning.

14

The book Snow White and Russian Red may be discussed also in relation to the category of experience. The turn to experience is allegedly another hastily announced turning point in the humanities.9

However, in my personal opinion, it seems to be stable (or perhaps more stable) and this opinion is based on strong foundations which are material at last (and not abstract – non-existent).

Experience understood as a bundle of experiences of a changeable subject, a bundle which is variable in time, is something that is most real, objective from the comparative point of view. In the shape and sound of words.

While ideologies, narratives and plots are abstract tools created by rulers and their servants (“court poets”) to serve their aims. They forced others to believe and immediately defeated them with this “weapon” (or in “fact”: instrument of aggression). They are a derivative of oppression, or a way to gain, keep and spread power.

15

The book and its film adaptation should be discussed separately.10

Both these works may be deemed outstanding, taking into consideration their proximity and – for the sake of the present paper – accepting the possibility of restoration of hierarchies in art and of so-called “restoration of the center”.11

Furthermore, abuse of another kind is possible. In their building material, both works contradict the possibility of thematization, they do not want to have “significance” at any cost. But to distinguish them from each other, the prose work (but not a novel) of this title might be referred to as a work about language while the film (a feature film?) – a work about imagination.

16

I had to express the above mentioned reservations in order to write clearly, taking into consideration current knowledge (or its changeable content12) and doubts.

17

Now I should only refer to what I understand as an economic crisis and as the economic crisis of 1989.

I understand crisis intuitively as a turning point, a time of verification or perfection of a previous system, or one of the ways of bringing another system into existence. At the root of the 1989 turning point there was – among other factors – an economic crisis: the failure of the previous model based on central planning, full employment and primacy of public ownership, which was co-dependent and simultaneous with limited independence and a shortage of democracy. The Round Table, the most obvious result of which was the election, referred to as contract election, brought about a much more important change: an economic transformation, the result of which (or perhaps its tool, cf. “shock therapy”) was another economic crisis.

In 2014 we celebrated a “round” anniversary of those events, which might have been an opportunity for re-evaluations or a time to explode myths and paradigms (of the free market, restrictive fiscal policy etc.). However, so far this has not contributed to achieving any consensus about what “really” happened nor about its results. What did the process of changing ownership relations and shaping or re-shaping the elite look like? What are their advantages and disadvantages? And this is where the aforementioned war of narrations takes place, one of many instances of the “Polish-Polish war.” Reminescent perhaps (and perhaps not) of Gombrowicz’s “duel of face-making.”

Both works, the book and the film, are of implicit character – they do not participate in the dispute at a high level of literality. They suggest another perspective, one that is minimally “comparable13 to what the Orange Alternative proposed at the end of 1980s, beyond the unjustified loftiness of the authorities, the opposition, and religion.

It is not the aim of the preceding paragraph to deny the importance of this dispute.

The relationship between awareness and economy, partly complying with what Marx said, may be both symmetrical and asymmetrical.

Let me return to the inadequate but incidentally useful abuse related to thematization. The domain of the “language war” in Masłowska’s book, and of the “imagination war” in Żuławski’s film is awareness, its status and transformations. Economy and its crises may either be its catalyst, its result, whether minimal or decisive, or may be happening beside it.

However, in order to meet the theme of the monographic issue, I will emphasize them, presenting both their interaction and independence, decorativeness.

II.

1. The book

While one group of readers waited for a novel dealing with the turning point in history, it seems (and this is a good word) to have been written for another group of readers (who appeared and will appear after it had been written but also were created as a result of its having been written).

And it was a different book than expected, which became the reason for its artistic success.

Its “theme” (Heidegger’s quotation mark14 is an appropriate tool) is language. But in the end it also becomes its victim. And as a result, all that the language tries to convey, “represent,” becomes its victim: ideologies, values, patriotism, customs, construction of an individual with their priorities, subjective line of life, ways of coping with the crisis, both individual and economic. Both a proposition and its opposition.

As Ferdinand de Saussure already observed, language is self-reflexive and refers to itself.15 Thus an honest analysis of “history,” history of economic crises included, may begin with an analysis of how the language used for narrating these crises is described. The language itself should be deconstructed, and expose its inherent contradictions and hidden ideological presumptions.16

Instead of analyzing what is openly expressed with language, one should analyze what is happening on the hidden plane.

The language of the Polish People’s Republic and the language of the Third Republic of Poland are characterized by inadequacy, an incompetent attempt to fill in the gaps. Any social system is rickety: it is enough to analyze, say, its linguistic foundations.

Dorota Masłowska uses surprising juxtapositions which are far from what one is used to, in order to expose their conventionality, falsehood, instrumentality.

According to the dominant narrative, the year 1989 in Poland is perceived as a great victory in which not a single shot was fired, a model to be imitated by other nations, the beginning of the Autumn of Nations.

The author does not argue with this view, nor does she claim the opposite. She proves implicitly that neither of these theses is absolute, both are simplifications, Misrepresentations.17 She presents people who are lost, whose speech is a conglomeration of the old and the new: relics of the People’s Republic of Poland, pop culture, primitive early advertisements of the cheapest of products, like candy bars or washing powder, because they simply cannot afford true capitalist luxuries (like a new car or a detached house in a new, rich housing estate).

Masłowska’s protagonists are full of contradictions (i.e. are attractive from the point of view of dramaturgy). On the one hand, they beef about the “Russkis” (the word used in the book), are afraid of them, blame them for all the evil (kidnappings, disappearances, poverty), and on the other hand, they complain about the “No Russkis Day” when it is not possible to buy addictive substances, cigarettes, alcohol and drugs, which they compensated for by inhaling instant borsch.18

They wage the eponymous Polish-Russki war under the white-and-red flag, which means precisely that under the same banner they wage a war with themselves and with one another19,20 their past and their habits. They are ambivalent: attraction is at the same time repulsion. What they try to repress, what they are ashamed of, is the “constitutive” part of their personality and partakes in providing pleasure, satisfaction, and a sense of being rooted.

2. The film

Nails’ loneliness, otherness or conflicts can be seen in a different light thanks to the art of film making. He lives in a detached house which was built in the age of Gierek21 and which is surrounded (besieged) by blocks of flats of prefabricated concrete.22 He has a different home than the others, a different starting point. His mother runs a small business in the form of a „horrendous solarium”.

His loneliness is also visible in the largest crowd scene, during a fair. Humbled by being dumped by Magda, he tries to introduce his own order, seize power (over everybody) in order to win his girlfriend back. He fights against the other participants of the fair who approve of the hierarchy headed by Robert Sztorm, the sponsor of the beauty contest which Magda is expected to win. Nails, probably the son of small business owners who began to grow rich in the 1980s, loses to a model of a businessman which appeared a decade later.

The interior decor reminds one about the shift from the old to the new. Wood paneling, unit furniture used as a wall to divide a room, a synthetic blanket with a pattern made to resemble the coat colour of a tiger (a substitute of tiger skin, the aesthetics of a fake), clothes, particularly those of older people. An old Polar washing machine struggling to wash off the new, unexpected “capitalist” dirt. The Polish Fiat 126. The chav subculture of that time. The aesthetics of the black BMW. The 1990s Polish rock music playing in the background and the obligatory discopolo23 at the fest. And finally, after Nails dies in the film, there’s the deserved “paradise”. Not a metaphysical one as someone might expect. A housing estate of detached houses built by a developer, with a very dense neighborhood of equally luxurious, identical houses. In other words, a goal pursued by many Poles in the first decade of the 21st century and nowadays.

An intriguing element is the motif of siding, an external decoration, an overlay, a mask, popular in the 1990s and used to cover the façade of a house at least two decades older. In the apocalyptic vision of Magda it appears to be of “Russki” origin, thus faulty; and during the celebration of family barbecue it begins to come off the walls, causing the death of all the members of Nails’ family, and in the end his own.24

Deconstruction takes place,the certainty is unmasked as something extremely conventional, but also oppressive to the individual and only beneficial to the system.

In the book: this deconstruction is achieved by means of language, which has been discussed. In the film by means of imagination: let us take for example the “meaningful” scene when Nails is being interrogated by a policewoman played, not without consequences, by the author of the book. In the wake of a war the author gets nervous and says: “there’s nothing. In these circumstances I have to write everything in this machine.”25

The walls of the police station turn out to be made of cardboard, to be conventional. Everything that Nails lived by, that fuelled his sense of drama, proves to be artificial: “Styrofoam, glass wool and cardboard. Is this what this city is built of? I am a trained dog.”

The following may be meaningful: the place that seemed to be a police station proves to be the backroom of a school (coalescence of the place where norms are passed and the first normative socialization occurs with the place where obedience to these norms is controlled).

Both the old world and the current one, its epigone, have gone bankrupt.

Everything is a matter of convention. Instead of a “decent interrogation,” there is a “mental electroshock therapy.” And only this proves to be real torture. Nails is too weak for that (Nails – in Polish Silny “strong” – here we observe an oxymoronic relationship between the name into which a declaration is inscribed and the reality). He decides to kill himself. Or he assumes that the wall which he about to hit with his head is fictitious, just like the police station in which he was held. But this second confrontation proves to be fatal. He lands in the props department of a film set, where various clothes are hanging (they may be perceived as clothes, as disguises, as social roles one must assume for this or that occasion). In the background he can hear slogans which construct the deconstructed awareness: Gierek’s “Will you help?”, the announcement of Karol Wojtyła as the new Pope (“Habemus papam”), Lech Wałęsa’s voice from the Gdańsk Shipyard in August 1980.26

The problem of narratives and their self-interested nature is emphasized in the film too. In the talk-show Nails answers the demand of both the host and the society: “so I tell you right of the bat what I have learned from cartoons and religion lessons at school.” Nails (or his author, who tells him what to say) appears in almost every scene of the film, and at the end addresses the spectator in a paraphrase of Hamlet’s monologue: “Do I live or not? If not, tough luck! It will hurt...”. It may be a question about the state of awareness, autonomy of an individual and objective existence of “the world” perceived by others in the same way; something entirely different that does not come to my mind at present, and also, in accordance with “the assumptions” of the work, none of these.

3

The main problem of the protagonists of the Wojna polsko-ruska (besides looking for the mirage of “love,” mutuality, community) is poverty: economic and “spiritual” and always relative. Difficult to bear because of their aspirations, both great and one-sided, which result from the sudden coming of capitalism, a world of advertisements, which creates (artificial) desires and replaces (natural) needs. An irrational hunger which cannot be quenched, fueled by the information presented by the media, and later also fueled by the people who have accepted it as their own.

It seems that there is also a real insufficiency. The breaking of the former social bonds, which have not been replaced with new ones based on new rules. This results from unemployment, economic recession (due to a change in the markets as well as the geopolitics of trade and modes of exchange) and inadequacy of educational curricula for the new requirements.27

The decline of the center understood as a shared set of values and the center of administration (i.e. a departure from central planning, from a state which declares the intention to guarantee social justice, from full employment and a welfare state variously understood).

The insufficiency is planned in the new system, too. The political and economic enslavement is replaced by another kind enslavement, with the “help” of economics. Shortage of goods and poor organization of work are replaced by shortage of free time, theft of time, an imperative to pursue a career, and the will to have full control of the employee. And in spite of such work, it is still impossible to satisfy the desires created by the system. Those who “cannot afford that,” are the addressees of the excluding “advertising” slogan of one the hypermarkets: “Not for idiots.” The new identity is determined by the brands with which people surround themselves (a BMW but also poor substitutes of luxury in the form of junk food at a fest or from a local fast-food).

Just like before, the system serves itself and the individual is persecuted. The individual is trying to climb the social ladder, take a higher place, but by acting according to the methods of the system (the imperative to acquire more wealth by hook or by crook) and within its logic (money as the most important value) they simply justify the system. The individual may be its last or at best its “first servant.”

What changes is only the type of hierarchy. Earlier it was apparently built on values, the Decalogue, the family, patriotism, the sense of community, whereas the current criteria, equally illusive, include money, fame, selfpromotion, gadgets, media publicity, popularity, clothes, car, furniture and accessories in one’s apartment or detached-house.

4

By applying an already outdated methodology, one might try to compare the book to the film.28 However it would be contradictory to the world views on the basis of which they developed and an attempt to create universal, comparable essences, which they do not exhibit.

Even the earlier (“mapping,”29 didactic) statement that the book about a “war” is a story about language whereas its film adaptation is a story about imagination may be investigated as an untruth, graded from simplification, to misuse, to falsification.

It is impossible to make a thorough comparison of the two. The idiomacy within conventional genres aside, they also represent genres which are absolutely dissimilar.

Both works are built on the escape from thematization. The crisis which was mentioned above is a background in each of them, its secondary status emphasized continuously. Comparison e.g. of the ways in which the crisis is presented would be a violation of their “meaning.” To give examples one after another would only result, more and more harmfully, in passing over of their natures in silence. The less about it, the better.

The concept of adaptation does not provide a connection between them either.30 It is only a commercial trick (a best-selling book as the starting point for the promotion of a film).

Masłowska’s book is a sort of a hip-hop poem,31 a digressive one, referring perhaps to the romantic „model.” Written in prose, in which ironic rhymes appear every now and then. Speckled with references which dominate the original content and begin to modify it. Built on linguistic and cultural calques, which are often distorted (by the plot, the chronology, the causeand- effect relations; the structure – e.g. by anastrophe). Also drawing from Gombrowicz, whose work in turn was founded on Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy and struggle against stereotypes about the Polish nature.

Both the book and the film are built from loosely shuffled cards of scenes. Reconstruction according to chronology is possible, but it would have an unfavorable impact on the whole (the pretextual plot is purposefully weak, though it contains a few mysteries).

Due to its substance, the film is closer to a “mass audience” (this is another out-of-date category). The main character was played by Borys Szyc who at that time had reached the height of his fame. He appears in every scene, which makes the film more consistent. It seems that the female characters are more distinct in the film than in the book. Screenplays are usually written in a less subtle way. Screenwriters were also looking for stereotypes which were hidden in the nuanced book to build the visible plot on. And beneath it there is a frantic interplay of meanings.. Perhaps it was the desire to find support in a convention, the need for a clear conclusion, that gave the film its ending (not present in the book), i.e. a housing estate of detached houses built by a developer. And a whole array of “national themes.” A film moves the spectator back in time using pictures and sounds, it achieves regression in a different way. Short snapshots are more meaningful, like in a music video.

The promotion campaign is another matter: it attempted to present Wojna polsko-ruska as a film for everyone, which deals with seemingly simple issues. One would have to exhibit maximum incompetence to interpret it in this way. However, while the early readers of the book were young, they belonged to the elite.

Further search for such comparisons would be a tautology. They do not lead to any new conclusions. These are to be sought elsewhere.

III

Economy does not turn out to be the main driving force behind the protagonists’ actions in the book or the film.

One may of course give more examples in the field of economics, but this will not change the general view, i.e. my interpretation. This also would be tautological.

The economic crisis is one of the components of the general crisis, unintentionally “expressed” in both works. If, as such, it may be considered the “theme” of the book and the film at all, as they ontologically strongly object to thematization.

But the protagonists – and this is also important – are not aware of it. Their dramatic situation consists also in the fact that they are like flies whose jars of artificial honey have been changed over: the “communist” for the “capitalist” one. They vacillate, they are unhappy, but it is difficult for them to find the real psychological, social, and economic causes of their state.

Their subjective crisis is a result of the fact that they mainly see the economic crisis. And they reduce their actions to money. In this way coming out of the real crisis becomes impossible for them. This crisis may be termed the base one. Perhaps this statement refers also to all the crises, erroneously defined as economic ones, including the current one.

Except that one should be careful in drawing such a general conclusion, because (as a generalization) it goes against the two works discussed.

However, let us come back to the characters in Wojna polsko-ruska. Their actions are harmless and inefficient, and despite their polemic nature, they only serve to confirm the order of things. One example is the attempt to wangle money from Robert Sztorm, the producer of amusement parks, king of sand.32They organize their lives around money and its lack, and thus they confirm its primary value. Greediness amounts to desire for money (the ability to “buy the fest”: fries, coca-cola, or a new house in a new housing estate). Whereas one of the more “real” reasons of the defeat is the inability to communicate or to reach a compromise, which causes loneliness. Or the ability to stand at the side (oversight).

Nails is a sexaholic who functions in the rhythm dictated by the erections of his penis, which he refers to as George (“George governs Nails”)33; he dangles visions of patriotism; during “the lecture” on the beach he conjures up a utopian economic model founded on sand, and not on gold or oil.

His girlfriend Magda, not mature enough for a relationship, would prefer someone more influential who could help her build her modeling career (the union of power and libido which was mentioned before). Thus Nails must find a substitute. George’s loneliness is one of the driving forces behind the story. Nails meets Angela, an artist-satanist, who wants to pursue a career (this time a poetic one) at any cost, Nata (Natalia Blokus, a representative of the species Homo Blokus), a chavette who loves to sniff instant soups and who is more “masculine” than he is, and Ala, from a Catholic youth movement, who appears to be the biggest playgirl of them all.

Nails’s only potentially possible and promising relationship is the one he has with Magda. However there is an obstacle, described as Magda’s “gangrene” (of her leg); here it is an obscure metaphor of unwanted pregnancy and motherhood, which causes disability (the motive of walking on crutches), the sense of being inadequate, and excluded. This also seems to be a sign of the times. A world in crisis has turned upside down. Starting a family is has gone out of fashion. What counts more is autonomous sex which is alienated from family life. Not to mention the economic and social impediments which await a young married couple. From here it will be twenty years before pro-family policy is declared and a minimal system of benefits such as the “large family card” (which entitles one to discounts and additional services), tax reliefs, or a newborn allowance is introduced.

As I keep emphasizing the economic aspect, I realize more and more how difficult it is to speak about the economic crisis alone and leave out the social crisis or the crisis of world perception; and how difficult it is to delimit when a crisis ceases to be economical in nature. And which crisis was caused by which. Perhaps it is easier to make such a distinction in a historical paper, but not in an anthropological one.

It is becoming more and more obvious that a division of the world into disciplines is arbitrary and that holism is the alternative and that the cognitive apparatus is constructed on an ad hoc basis for the sake of a single statement.

It seems that in the narratives written following the decline of realism,34 it is not the economic aspect that is assigned the decisive role. Psychology, the need for participation, the problem of responsibility are more important. The organization of social and economic life is only one of the aspects, or it is left out.35

In the background there is the question – one which is recurrent in the public debate – about the actual primacy of economy over other spheres of life or life in general, and the question about the paradigm of growth in economics itself. The differentiation between wealth and welfare. It seems to be more adequate to speak about a crisis in general, economy being only one of its aspects. A crisis that affects us, to which sometimes war becomes a response.36

Text translated into English: Agata Jankowiak

Łukasz Mańczyk. Lawyer (Jagiellonian University), screenwriter (Łódź Film School). PhD student at the Jagiellonian University. Author of four books: “Służebność światła” (Kraków: Homini 2004), “Affirmative” (Beograd: Trci trg 2006), “Pascha 2007/punkstop” (Kraków: Towarzystwo Słowaków 2009), “Biserka” (Kraków: Universitas 2015). Town councilor in Krowodrza, 5th quarter of Cracow.

ENDNOTES

1 The category of memory in the objective sense or in relation to a community (e.g. memory of a nation or of a generation) is questioned. It is contrasted with subjective memory, which is close to interpretation, a carrier of meaning but only individual meaning. It might change in time (through re-interpretation of events and change of importance ascribed to them). I recommend e.g. Tomasz Maruszewski, Pamięć autobiograficzna [Autobiographic Memory] (Gdańsk: GWP, 2005).

And particularly: Andrzej Falkowski, “Pamięć i wiedza w kontekście rozwoju poznania naukowego” [Memory and knowledge in the context of the development of scientific cognition], Nauka 2004, nr 2, p. 105–124. In this paper the author takes as a starting point the (classic) definition of epistemic truth by Thomas Aquinas and in the course of reasoning contrasts it with successive contructivist definitions. His paper has a practical bent. The author uses real-life examples to prove that truth is a construct, and memory not so much refers to the past as is subject to transformations for the benefit of the present and the future, in order to guarantee that the new actuality agrees with the interpretation of the past.

And thus the author gives an example of a product tester whose memory changes, so that it is more consistent with the information gained later from a commercial (the memory of an unsavory juice changes into a memory of a savory juice under the influence of an attractive commercial broadcast sometime after he had drunk the juice).

Using the well-known drawing “duck or rabbit,” the author confirms, following his precursors, that the interpretation of reality depends on the observer’s information resources and his analysis of these resources. This is why “the same” situation will be completely different for different persons.

The author speaks about the paradox of the development of science, which does not expand our knowledge of reality, but only produces a new image of reality, again and again (p. 108).

Surprising conclusions may be drawn from the examination of the opposite, i.e. the process of forgetting. The author contrasts curves of forgetting, the gestalt theory of forgetting (the hypothesis of memory trace), and interferential concepts of forgetting (replacement of material by one of similar kind) with possibilities not so much of forgetting (repressing) as a gradual, partial or complete loss of access to the remembered data. Retrieval cues offer a possibility to re-gain access, if an appropriate stimulus of appropriate intensity is created.

Falkowski speaks about memory as a totally personal domain in which once this, once that information takes the most important place (cf. the notion of architecture of memory – J. R. Anderson, The architecture of cognition [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983]).

He disagrees with the idea of repressing information, and substitutes it with the hypothesis of a gradable loss of access. There exists a possibility of restoring access if an appropriate stimulus with an appropriate intensity is created.

He points to phenomena, familiar to Western intellectual thought, such as the imagination inflation and backward framing, i.e. readjusting memory to information and not vice versa (cf. also the notion of editing memory).

This paper may lead to the conclusion that perception and interpretation will always be instrumental in nature. Reality (including book reality and the reality pictured in reading) is a point of reference, a state to which the individual refers in a dynamic manner and never an “attitude.”

2 It is not about “the end of history” in the sense of reaching the apex (the end) of social evolution which Fukuyama proclaimed (see e.g. Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man [reissue edition Free Press, 2006]).

But, just as with memory, it is about the question concerning the treatment of history as an objective sequence and a set of facts. History is a narrative. It has a narrator, so it is not objective, but it serves the interests of this narrator.

Besides, “the story [...] tells you something about the person, what they feel and how they evaluate and experience the world” (Graham Gibbs, Analyzing Qualitative Data [London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2008]).

The monopoly of professional historians, authority figures, and also authoritative publications and the catalog of the preferred forms have been weakened. Cf.: “Each individual gains a possibility to express oneself freely, regardless of their narrative predispositions” (Maria Antonina Łukowska, “Badania nad opowieścią wspomnieniową” [Studies on reminiscence narrative], Łódzkie Studia Etnograficzne vol. 30, p. 53, [Łódź: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze, 1991]).

And “what an anthropologist should be most interested in does not have to pertain to reaching the sources of knowledge about the respondent’s past reality, but just to the knowledge about his ordering of the past” (Joanna Rembowska, “Narracje pamięci” [Narratives of memory] in: http://www.etnologia.pl/multi-kulti/teksty/narracje-pamieci.php, access: 2015/1/25).

And more about the subjectivism, which constitutes memory and is constitutive for memory: “memory which invariably constructs the meaning of the past, constantly depends on the moral system of the individual who remembers, on their hierarchy of values, their beliefs and tradition” (Joanna Rembowska, op. cit.).

3 Let me remind the reader about the following opposition: cognitive optimism, which assumes the possibility of knowing and checking the results, vs. cognitive pessimism (skepticism, criticism): the impossibility of reaching the truth (the impossibility of deciding about its content or absence of this “truth”). I recommend a systematizing paper with rich literature:

Witold Marciszewski, “Racjonalistyczny optymizm poznawczy w Gödlowskiej wizji dynamiki wiedzy” [Rationalistic cognitive optimism in Gödel’s dynamics of knowledge], http://www.calculemus.org/CA/epist/marc-optymizm.html, access 2015/1/31.

The current paper is written in accordance with the latter concept.

The opposition cognitive optimism vs. cognitive pessimism is reflected in the concepts of truth, in doctrine (e.g. in literary studies) and also in practice. For example, in law there functions the concept of material truth and also the concept of legal truth, based on the presumptions of law, legal fiction and unanimous statement of the parties.

See. e.g.

Filip Przybylski-Lewandowski, “Domniemanie prawne” [Legal Presumption], in Jerzy Zajadło (ed.), Leksykon współczesnej teorii i filozofii prawa [Lexicon of Contemporary Theory and Philosophy of Law] (Warszawa: C. H. Beck, 2007), p. 55.

Andrzej M. Świątkowski, “Fikcje prawne w instytucji rozwiązania stosunku pracy” [Legal Fiction in the Termination of a Job Contract], Państwo i Prawo [State and Law] 7/2010, pr. 18.

Legal truth (not necessarily consistent with the material truth) may also become the basis for a legal statement.

Example of a legal presumption: Polish Law on Road Traffic, Article 130a par. 10: “A vehicle taken into custody under par. 1 or par. 2 and not reclaimed by an authorized person within 6 months from the day it is taken into custody shall be deemed abandoned with the intention of disposal”. (Dziennik Ustaw [Journal of Laws] 2005, No 108, item 908).

Example of legal fiction: substitutive delivery which consists in declaring a letter delivered if the addressee is absent at the moment of delivery or refuses to receive the mail (e.g. Kodeks postępowania administracyjnego [Code of administrative proceedings] Art. 43, Dziennik Ustaw [Journal of Laws] 2013, No 0, item 267).

The current paper is not free from similar fictions and presumptions either, although they pertain to the field of literary studies and anthropology.

Cf. also:

– the coherence theory of truth: true is what is inherently coherent. This theory assumes that what is true in one system may be at the same time not true in another. Formal criteria (e.g. logic) and not substantive ones are decisive. See the works of the author of this theory, e.g. Francis Herbert Bradley, Essays on Truth and Reality (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1914).

– the consensual theory of truth: true is what a given group of people deem true. Here one finds a great scope of literature, from e.g. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Create Space Publishing Platform, 2011, (a social contract which establishes authorities, as a result of shared conviction);

to Juergen Habermas on establishing (consensual) truth in a so-called ideal speech situation; see e.g. Craig Calhoun et al. (eds), Contemporary sociological theory (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), pp. 352–353;

finally to Karl Otto Apel and his theory of apriority of social communication and communication ethics.

– the constructivist theory of truth: truth is constructed. It may also be the result and tool of class struggle. I recommend the paper: Andrzej Falkowski, “Pamięć i wiedza w kontekście rozwoju poznania naukowego” [Memory and knowledge in the context of the development of scientific cognition], Nauka 2004, 2, pp. 105–124.

– the minimalist (deflationary) theories of truth: truth is a sequence of expressions, whose occurrence may be ascertained (established) but it is not subject to further analysis (“verification”): e.g. the existence of a certain, e.g. literary, statement, is ascertained but its relation to its subject (or reason) is not examined. Cf. e.g. Cezary Cieśliński, Deflacyjna koncepcja prawdy. Wybrane zagadnienia logiczne, [Deflationary conception of truth. Selected logical issues] (Warszawa: Semper, 2009).

In reporting this issue I used also the synthetic presentation by Krzysztof Mądel, “Teorie prawdy” [Theories of Truth], a multimedia presentation for the seminar “Prawda w medycynie” [Truth in Medicine], Collegium Medicum UJ, Cracow, November 9, 2006 (madel.jezuici.pl/files/slide/teorie_prawdy.pps, access: 2015/1/31).

Krzysztof Mądel presented the following taxonomy of theories of truth: I – substantial theories (correspondence theory, coherence theory, constructivist theory, consensual theory, pragmatic theory); II – minimalist theories (performative theory, redundancy theory, semantic theory); III – classic theories (Thomas Aquinas, Kant, Hegel, Kirkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger and even Foulcault and Baudrillard); IV – category of truth in context (in relation to academic disciplines, e.g. sciences and religion e.g. the infallibility of the Bible).

It is not my aim to relate Krzysztof Mądel’s views in detail, nor to engage in potential polemics. The reason behind this footnote is the desire to justify the methodology of my article which is close to the theories deemed minimalist (especially the correspondence, coherence, constructivist, consensual, redundancy and semantic theories), and the so-called truth in context (in relation to humanities).

4 The key notions of contemporary humanities are referred to so often and in so many different ways that it is difficult to determine their consistent interpretation (semantic range). Examples of source literature:

– indeterminability: see the footnote about the conception of cognition and theory of truth.

– fluidity: see Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000).

– continuous interpretation and (re)interpretation: “culture [...] understood as a never ending process of semiosis (creating and interpreting signs)” (Anna Burzyńska, “VIII. Semiotyka” [8. Semiotics], p. 258, in Anna Burzyńska, Michał Paweł Markowski, Teorie literatury XX wieku [Theories of Literature in the 20th Century] (Kraków: Znak, 2009).

5 What strengthens (explains) the essayistic thesis here is again a purely scientific enunciation:

“choosing a narrative as a source of knowledge, one must always remember that it cannot be explicitly defined or classified into particular structures established by the researcher. A narrative thus becomes an irreplaceable piece of evidence of certain aspects of the respondent’s biography. The narrative ‘gives the respondent a chance to speak for themselves’”(Gibbs, op. cit., p. 109).

In the same way one may describe the relationship between facts (including the economic crisis in which we are interested) and Masłowska’s novel and Żuławski’s adaptation.

Whereas Joanna Rembertowska, who provides the above quotation, sums up: “Thus he [the author] gets an opportunity to create and maintain the image of his own identity. By means of the narrative he also shows the way in which he perceives the world and, what is more, the way in which he perceives himself.” (Joanna Rembertowska, “Narracje pamięci” [Narratives of Memory], op. cit.).

And she continues: “An anthropologist ‘focuses not just on what people said and the things and events they describe but on how they said it’ (Gibbs, op. cit.)”.

One may relate this statement directly to the examples of artistic expression in which the form is of primary importance.

“Being both the narrator and the protagonist of our past we are the ones who attribute meanings to it” (Katarzyna Kaniowska, “’Memoria’ i ‘postpamięć’ a antropologiczne badanie wspólnoty” [’Memoria and ‘Post-memory’ and anthropological study of community], Łódzkie Studia Etnograficzne [Łódź Ethnographic Studies] vol. 13, p. 62).

6 See the footnote about the indeterminability, fluidity, and continuous interpretation and (re)interpretation.

7 This one and many remarks to follow are of essayistic and polemic character. Seemingly they are out of place in a research paper and outside the working problematization of this paper. However, this will be settled in favor of this paper in the last footnote.

Justification: discussing both these works in the way they have been discussed would lead to conclusions which have already been reached. Yet these works discuss issues which are rather new and do it in a new way, additionally trying to negate some ways of thinking, and the existence and rank of some social phenomena. Although only non-verbally or implicitly, they propose new theses, which were vague in the language used before. Or (in the extensive version) they engage in polemics with many former ones. Thus it seems justified to use more adequate methods, including ones constructed in the course of discussion. Ones that refer to straightforwardness and oppose the tendency to classify. Hence the essayistic mode, leaving out linearity and straightforwardness.

Because of the brevity of the present study, this method must partly explain itself (using examples) in the course of implementation.

8 Among many others, the following key to Trans-Atlantyk may be formulated: the economic and political crisis and the identity crisis co-exist and create each other. Just like in the works of Masłowska and Żuławski, and also in the context of war, understood not conventionally, hallucinatorily, oneirically, but literarily.

9 In the wide spectrum of social sciences, particularly in sociology, e.g. Anna Wyka, Badacz społeczny wobec doświadczenia [Social Researcher and Experience] (Warszawa: Instytut Filozofii i Socjologii PAN, 1993).

In academic disciplines known as humanities, particularly in anthropology, e.g. Ewa Domańska “Doświadczenie jako kategoria badawcza i polityczna we współczesnej anglo-amerykańskiej refleksji o przeszłości” [Experience as a research and political category in contemporary Anglo-American reflection on the future], in Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska and Ryszard Nycz (eds), Nowoczesność jako doświadczenie: dyscypliny – paradygmaty – dyskursy [Modernity as experience: disciplines – paradigms – discourses] (Warszawa: Academica, 2008), pp. 131–142.

10 Dorota Masłowska, Wojna polsko-ruska pod flagą biało czerwoną (Warszawa: Lampa Iskra Boża, 2002);

Wojna polsko-ruska, written and directed by Xawery Żuławski, 2009. All the quotations from these works were translated for the sake of this paper by Agata Jankowiak.

11 Detailed explanation is beyond the scope of the current article, but the status of masterpiece is related to the belief that all works of art may be hierarchized on the basis of one unitary key. This view was criticized a long time ago by Janusz Sławiński in a paper published on 5 March, 1994, “Zanik centrali” [Decline of the Center], Kresy, 1994/2: 14–16.

12 It is recognized as one of the causes for the crisis of humanities. In the Polish context this issue was discussed in the monographic edition of the monthly Znak with the subtitle “Bankructwo humanistyki” [Bankruptcy of Humanities]. See Znak 2009/10 (663).

13 Thus I am inclined to agree with the (dominant) opinion that comparative studies are not possible because there are no common comparative criteria for independent entities, symptoms, activities. Idiomaticity excludes the scientific dimension of comparison but not the educational one.

Besides, “Jonathan Culler expresses the opinion that the so-called crisis of comparative studies is first of all the crisis of ‘comparability’, which is connected with the impossibility of taking a neutral stand, a neutral research position” (Andrzej Hejmej, “Niestabilność komparatystyki” [Instability of Comparative Studies], in Wielogłos 2010/1–2 [7–8] [Kraków: Wydział Polonistyki UJ, 2010]).

This paper refers to: Jonathan Culler, “Comparability,” World Literature Today, Vol. 69, No. 2, Comparative Literature: States of the Art (Spring, 1995), pp. 268–270.

14 More on this topic, see e.g. Daniel R. Sobota, Źródła i inspiracje heigeggerowskiego pytania o bycie [Sources and Inspirations of Martin Heidegger’s Question of Being], vol 2: Filozofia życia, filozofia religii i filozofia egzystencji [Philosophy of Life, Philosophy of Religion and Philosophy of Existence] (Bydgoszcz: Fundacja Kultury Yakiza, 2013), pp. 509–513.

15 The main thesis of the researcher was that the subject of linguistics is language considered in itself.

See Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York: McGraw-Hill 1966).

See also: Ferdinand de Saussure, Writings in General Linguistics, trans. Carl Sanders (Oxford University Press, 2006).

16 An example crossing the fields of linguistic customs, modern history and politics: the uncritically accepted saying “black is black, white is white” used as a slogan by a Polish presidential candidate, the former leader of a social movement aimed at introducing freedom and democracy, may be, contrary to the user’s intentions, a reflection of the post-colonial way of thinking and the heritage of the theory of white race superiority over the black race. Similarly the word “asshole” may be a hidden criticism of anal or gay sex, which is not procreative.

17 Cf. also the bon-mot “The truth? There is no such thing” in The Dark House, written and directed by Wojciech Smarzowski, 2009.

18 Perhaps the aim here is to find a metaphor for a general prohibition of trading on Sunday, which was the subject of public debate when Masłowska was writing her book.

It is (perhaps) that what is inhaled is red borsch, red being the color of the October Revolution. Instead of the western “white way” offered white powder (the genuine drug), there is the eastern “red way,” a substitute.

19Cf. Sonet IV by Mikołaj Sęp-Szarzyński “On the War We Wage With Satan, The World and The Flesh” translated by Richard Sokoloski: staropolska.pl/ang/baroque/Sep_Szarzynski/tekst_sonnet_04.php3

20

– Poles fight against Russians

– Poles fight against “Russkis”

– Poles fight against Poles

– each of them fights an internal fight (say because of the internalized „homo sovieticus” from Father Józef Tischner’s writings).

The conflict equally concerns the struggle between two nations, whether real or imaginary (Poles, Russians, “Russkis”), that within one nation (Poles vs. “russified” Poles) as well as the one fought internally by an individual about which stance is going to win and in which circumstances.

21 Edward Gierek – one of the party leaders of the Polish People’s Republic, he governed in the 1970s. His name is associated both with Poland’s civilizational advancement, the so-called (economic) miracle on credit, and the economic, social and political crisis which ended his leadership.

22 This brings to mind the situation depicted in the film The Beads Of One Rosary (written and directed by Kazimierz Kutz, 1978) in which the main protagonist, a retired miner, fights to be allowed to remain in his worker’s house, even though a housing estate of tower blocks is being built around it. He struggles for his own dignity but also for the good conditions of life for the others (“They will see and say: ‘This is how the miners once lived and this is how they live now’”).

23 Disco-polo is a kind of music, popular in 1990s Poland and similar to disco music, “characterized by kitsch and simplistic performance” (http://sjp.pl/discopolo, date of access 23/11/2015). The genre resembles the earlier italo-disco, which emerged in Italy, and its development was simultaneous with that of Balkan turbo-folk, although the Polish music does not feature nationalist elements, as it was the case in Yugoslavia and the former Yugoslavia during the civil war and after it ended.

24 In Wojciech Kuczok’s Gnój [Muck] an old, faulty sewage system plays a similar role. It breaks down towards the end of the book and causes a complete destruction of the house and its inhabitants.

25 Analogy to the film Naked Lunch (written and directed by David Cronenberg, 1991) in which a fancy typewriter one is of the motifs: concentration on the tool with which one creates shapes and poor substitutes of meanings.

26 Slogans which ceased to unite. One may pay attention to the scene when Nails and his friend “play” with walkie-talkies. The reason for their fight and arrest by the police is the lack of a password, which makes their further conversation impossible (“wrong password”).

27 For example, the young characters in the film frequently discuss studies in economics and marketing at university, which have turned out to be merely degree factories. The quality of being conventional, absurd, oxymoronic, false, useless, incompatible with the alleged “nature of things” is also seen in the term “sandworks” which defies all common sense (and describes the basic activity of the richest businessman in the neighborhood, a local leader).

28 Cf. the above footnote concerning the question of comparability (the possibility of comparability). Comparative studies is one of the most important trends in literary studies. The term littérature compare appeared in France at the beginning of the 19th century. It was used with reference to comparison of works created in various languages and cultural environments. In 1954 the International Comparative Literature Association was established.

A question which is akin to the above is the considerations concerning the original and its copy, travesty, pastiche, as well as interdisciplinary research, e.g. study of the relationship between the original work and its adaptation (on stage, in film).

Nowadays the so-called crisis of comparative studies is being observed (as mentioned in the previous footnote). The parallel fall of structuralism (a belief that the whole world is constructed on the basis of the same rules, everything is interrelated and one thing results from another) was also of some importance. When it was decided that structures are nothing else than a contractual (artificial) construct, the ontological basis for comparability of particular works disappeared.

29 The notion of a map (or rather the lack of a map) is probably the best metaphor of the twilight of comparative studies and their impossibility (this also applies to all comparisons, and possibility of a hierarchy). This metaphor is often employed e.g. in the poetry of Andrzej Sosnowski. At the same time he refers to Elizabeth Bishop’s poem Map.

30 As is well known, e.g. from Adam Mickiewicz’s poem Pan Tadeusz [Sir Thaddeus], adapted by Andrzej Wajda (Pan Tadeusz, written by Jan Nowina Zarzycki, Andrzej Wajda, Piotr Wereśniak; directed by Andrzej Wajda).

31 It is even more clearly seen in the author’s second book, Paw Królowej [no English translation, lit. ‘The Queen’s Peacock’ but also ‘The Queen’s Puke’] (Warszawa: Lampa i Iskra Boża, 2005). And also in its adaptations, e.g. Paw Królowej, directed by Paweł Świątek, Teatr Stary in Kraków, premiere 2012/10/27.

32 Cf. the production of happiness – decreeing happiness; “castles in the air.”

33 The English translator of Masłowska’s novel Benjamin Paloff (Snow White and Russian Red, Grove Press, Black Cat, 2005) consistently uses the name „George,” which is the equivalent of the adapted form „Dżordż” used by the author (a spelling which represents the English pronunciation of “George”). It does not, however, reflect all the linguistic operations that Masłowska performs – the reasons, the means and the results of this adaptation.

The form “Dżordż” has not caught on in colloquial Polish. Benjamin Paloff’s intention must have been to render the author’s idea to refer to the main character’s penis using a familiar name which most likely had not appeared in (literary) Polish before and to represent its autonomy and individual, unparalleled features.

In the same way as English uses names such as “Willy,” “John Thomas,” or “Dick,” so Polish has e.g. “Wacek” (the diminutive of “Wacław”).

“George” (“Dżordż”) indeed has control over Nails throughout the plot of both the book and the film, hence its name is of primary importance.

In Polish “Dżordż” has humorous, frivolous overtones, and is perhaps of diminutive character. Outside Masłowska’s book one will not find a similar phonetic spelling.

This “Dżordż” is derived from the Anglo-American name, which acquires an additional, enriching and conflict-provoking – confrontative sense in the Polish-“Russki” context.

34 The one that is associated e.g. with the works of Honoré de Balzac, the author of The Human Comedy.

35 If it is at all. As I wrote before, by analogy to sonorism (an approach to composition in contemporary music) contemporary art is dominated by the reflection on language itself, and not on the aspects of the world subject to description. Reflection on language, on construction, on imagination as such.

36 In this way the anxiety implied by the word wojna ‘war’ in the titles of the two works becomes a means to express a general, contemporary anxiety and the current existential and political situation.

I began and I will finish this article (in an attempt to deliver a punchline) with a quotation from Andrzej Falkowski: “the respondent’s memory changes so that it becomes more consistent with the information received later” (Andrzej Falkowski, op.cit., p. 119).

And I will allude to Nails’s statement: “Now I know what to say. I am a trained dog.”

The aim of the so-called narratives of memory and of fiction is not the past (nor theory) but the reality and consistency with the present state, (artificial) unification. Memory is subjective. Just like – in this approach – history, it is not in service of the past (including commemorating people and events, in their interest), but of the people who live “here and now”. It is in the service of the present and the future. It is treated instrumentally not only by the “lords of memory” themselves (ideologists, leaders, copywriters, ghost-writers) but also by “average” users of memory, including the memory of crises.

The memory of crises (also economic ones) will changing depending on the individual and general situation and needs, so that as a narrative it can preserve the illusion of coherence “The traces of the events which are experienced will mix, collide, replace one another” (Andrzej Falkowski, op.cit., p. 120).

The present attempt at interpreting both works and the conclusion about its impossibility cannot deviate from the current (non-fictional) situation of the reader and spectator, including the one who is writing these words.

In research into memory, construction of history, typologies of truth, in considerations of cognizability and comparability, one can see a constant opposition of classic and constructionist (relativizing) approaches.

This article, which is developed both in the main text as well as footnotes and written in two different languages, is only an attempt to discuss this opposition. At the same time it is an attempt to speak about crisis narratives and the changing approaches to the possibility of remembering in general.

The end of this footnote may be considered to be the actual ending of my paper, developed in two dimensions, the impressionistic (essayistic) one and the scientific one (in the footnotes), and which also constates similar undecidabilities, and ways of coping with them.

This article has been published in the fourth issue of Remembrance and Solidarity Studies dedicated to the memory of economic crisis.

>> Click here to see the R&S Studies site