‘The spirit of the time left its stamp on these works ’: Writing the History of the Shoah at the Jewish Historical Institute in Stalinist Poland

ABSTRACT

The Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw was probably the only research institution in the Soviet Bloc and one of very few that undertook research on the Shoah during the 1950s. This article analyses the institute’s research and working conditions against the background of the general political regime under Stalinism in Poland. It argues that despite sometimes heavy-handed political biases in its publications, the institute made an important contribution to research on the Shoah. Its work also came to the attention of Jewish centres outside the Soviet Bloc, though it was seen through the prism of the Cold War.

Introduction

Das Amt und die Vergangenheit [The Ministry and the past] (2010) summarizes the work of an international research group, which studied the involvement of the German Foreign Ministry in the mass murder of European Jews over several years. The findings, which attracted wide public attention, erased the myth that the Auswärtiges Amt [German: Federal Foreign Office] had been a clandestine refuge for Nazi opponents. Instead, it exposed the active participation of the Foreign Ministry in preparations for and its conduct during the Holocaust (Conze et al. 2010). In 1953 Artur Eisenbach had revealed the involvement of the Foreign Ministry in the Holocaust in the Nazi policy of extermination of the Jews though this work was not as comprehensive (Eisenbach 1953). His study is also one of the first monographs ever published on the Shoah. 1 Although forming the larger part of the research on the Shoah conducted at the Jewish Historical Institute (JHI: Yidisher historisher institute/Żydowski Instytut Historyczny) during the first half of the 1950s, 2 Eisenbach’s book received little attention. The reasons for this are many. The institute published in Polish and Yiddish, and both these languages were little known in the West outside East European Jewish émigré circles. Also, interest in the Holocaust had been fading after an initial phase of intense interest in the late 1940s. The most important reasons are, however, the political distortions of Stalinism and the thoroughly Marxist methodology, especially in Eisenbach’s case. 3 During the Cold War such politically biased texts were read with hostility by readers in the West. The Yiddish press in the United States and Israel thus called the Warsaw Jewish historians derogatively ‘Yevsec historians’ or ‘Stalinist slaves’ whose work consisted more of a falsification of history than of history writing. Such assessments, which neither considered the political context of the JHI’s publications in the first half of the 1950s nor assessed their scholarly value, using the political jargon of the time, found their way into the Western historiography of the Shoah4 and can still be found in recent publications. A telling example is Sven-Erik Rose’s 2011 article on the perception of Yehoshue Perle’s ‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw] in the early 1950s. In his illuminating contribution on Perle’s radical witness account of the mass deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto in summer 1942, Rose refers to the JHI historians as ‘Jewish Stalinists’, 5 and so overlooks the vast literature on the situation of Jews in Stalinist Eastern Europe (Grüner 2008; Rubentstein and Naumov 2001).6

In this article I provide such a contextualization and discuss the potential and boundaries of research on the Shoah in Stalinist Poland. I begin with a short introduction on the JHI and its formation in the early post-war years. Then I shed light on the Stalinization of the institute in 1949–50 and analyse the impact Stalinism had on the activities and the publications of the JHI, against the background of general developments in Poland and how this was perceived in the West, especially in the Yiddish context. Finally, I examine the repercussions of anti-Semitism in the late Stalinist period for the JHI researchers and publications.

The emergence of the JHI

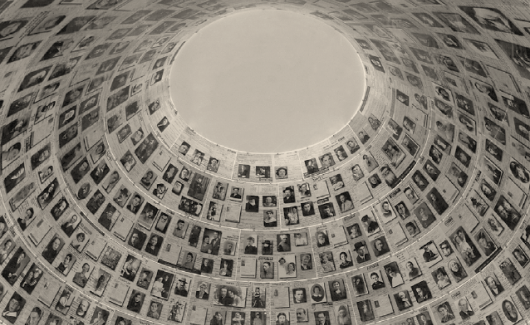

The JHI came into being in October 1947, when the Central Jewish Historical Commission [Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna] was transformed into a permanent research institution. The commission had been founded in late 1944 in Lublin by the Jewish historian and Holocaust survivor Philip Friedman (Grüss 1946, 6).7 In 1945 it was relocated to Łódź and then to Warsaw in spring 1947. Its purpose was to document and research the mass murder of Polish and European Jewry. To that end, the commission began to gather and assemble ‘all printed, handwritten or other materials, photographs, illustrations, documents and exhibits’ before the end of the war.8 The commission also drew up sources that documented the Jewish perspective on the German Occupation of Poland: interviews with thousands of survivors, both adults and children, were recorded. Today, more than 7,000 testimonies are stored in the JHI archive.

The best-known and most valuable collection is the secret archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, produced by the Jewish historian Emanuel Ringelblum and his underground Oyneg Shabes group. It is in two parts; the first was unearthed from the ruins of the Ghetto in September 1946.9 This served as an important impetus not only for the Commission’s work but also for the transformation of the Central Jewish Historical Commission into a permanent research institute.10 A year after the first part of the Ringelblum Archive was found, the Central Committee of Jews in Poland [Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce],11 a self-governing body of the then quasi-autonomous Jewish community in Poland, made the decision to turn the commission into the JHI.12 This took place in a period of relative political liberalism in Poland – at least as far as the Jewish community was concerned. Many Polish Jews that had survived the Shoah in German-occupied Poland or the Soviet Union still believed it was possible to restore Jewish life in Poland. Many Jewish institutions, such as Yiddish theatres and schools, newspapers and a printing house, were established at that time.13 In this context, the JHI could have filled the role of a scholarly institution of and for the Polish Jewish community. As such it would research the whole history of Polish Jews from the early Middle Ages onwards. However, the central topic of the work would remain the documentation of the Shoah.

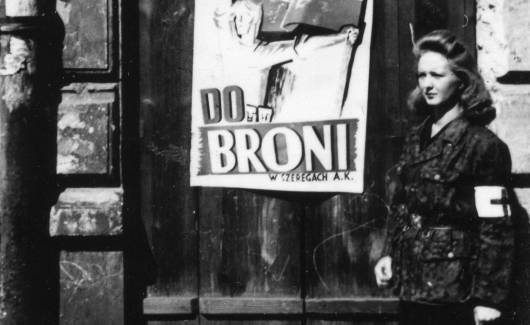

The first public opportunity for the JHI to present itself was the fifth anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising in April 1948. The anniversary was an international event, attended by many Polish, Polish-Jewish and international officials as well as by delegations from Jewish institutions. The festivities, which were prepared with the support of the JHI staff, began with the opening of the institute’s Museum of Jewish Martyrdom and Fight [Muzeum Martyrologii i Walki Żydowskiej] on the eve of the anniversary, and closed with the unveiling of Natan Rapaport’s monument dedicated to the Heroes and Martyrs of the Warsaw Ghetto the next day (Kobylarz 2009, 39 f.).14 Also in 1948 the JHI began to publish its Yiddish journal, Bleter far geshikhte [Folios for history],15 which addressed an international, Yiddish-speaking readership. However, in the second half of 1948, the political situation became tense. Within a year, the façade of Jewish quasi-autonomy of Jewish in post-war Poland was dismantled. Jewish activists from the Polish Workers’ Party (known from late 1948 as the Polish United Workers’ Party, PZPR) took over the Central Committee of Jews in Poland and all larger Jewish institutions. Other active Jewish parties were marginalized and subsequently dissolved (Grabski 2015, 199–202, 226–48). In summer 1949 the director of the JHI was sacked and the pre-war communist journalist and PZPR member Ber Mark was appointed to replace him.16 As a result, many former staff members, among them Nachman Blumental, the first director of the institute, and Rachela Auerbach, one of the few survivors of Ringelblum’s Oyneg Shabbes group, decided to emigrate.17

The transformation of the JHI into a Marxist‑Leninist research institute

As the Stalinist grip on Poland tightened including within the Jewish sphere, Mark speeded up the ideological redirection of the institute. The aim was to catch up with the process of ideological transformation, which had begun in Polish universities and research institutions two years earlier (Górny 2011, 43 f.). Mark quickly steered the institute on to a course that clearly followed the party line. This was characterized by an open adherence to Marxist-Leninist theory in historical research as well as the use of history as propaganda – especially of the Second World War and the Shoah – to legitimize communist rule in Poland and the position of the Soviet Bloc in the confrontation with the West. To underscore his commitment to communist ideology, Mark published a programmatic statement in the newly established Yiddish information bulletin of the JHI. In ‘Our Aims’, published in November 1949, he emphasized his ambition to transform the JHI into a Marxist-Leninist research institution: ‘The Jewish Historical Institute in Poland has the ambition not only to be the scientific centre of research on the most recent period of our history, the period of unprecedented annihilation, heroic resistance and rebirth, but also to become a centre of Marxism-Leninism applied in research on Jewish history.’18 This also meant, as the text continues, that the situation in the ghettos had to be analysed from the perspective of class struggle, and the character of the mass murder of Jews by the Germans in turn had to be explained as a consequence of the capitalist order in its imperialist guise.19

Mark’s articles suggested that his appointment as director was a radical break in the JHI’s work. However, although it was certainly a break, it was not especially radical. Mark, who was alleged to have a ‘too friendly attitude to people’ to become an influential communist functionary in post-war Poland,20 did not purge the ranks of the JHI. All staff members, including those who chose to emigrate, were allowed to keep their positions until they left and they remained on good terms with Mark after their departure. In September 1950 Mark exchanged letters with his predecessor, Nachman Blumental, and the former vice director, Józef Kermisz, who had settled in the Kibbutz Lohamei haGettaot. When they informed him of their plans to continue their research work in Israel, Mark congratulated them and assured them of his willingness to cooperate.21

Most of the historians who remained were members of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). Besides the directors – Ber Mark and Adam Rutkowski – there were Artur Eisenbach, Fraim Kupfer and Tatjana Berenstein. The only nonpartisan senior researcher who remained at the JHI was Szymon Datner, but Danuta Dąbrowska and Albert Nirensztein (Aaron Nirenshtayn in Yiddish), who joined the institute in 1951, were nonpartisan too.

It is also worth noting that although Mark had been a member of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP; Komunistyczna Partia Polski) since 1930, he had never been considered among the ideologically unimpeachable Jewish Party activists. Especially in the Soviet Union, where he spent the war years, he had been treated with suspicion by the authorities and also by some of his Jewish comrades. Shortly after he secured a position as a staff writer at Eynikayt [Unity], the official organ of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, Mark was accused of ‘Jewish nationalism’ and fired, something that made his situation precarious.22 After he returned to Poland in 1946, holding important functions within Jewish social life, Mark faced similar accusations. The most serious was at a meeting of the Jewish Fraction of the Polish Workers’ Party in October 1948, when Szymon Zacharisz – the leading figure among the Jewish Communists and architect of the Stalinization of Jewish life in Poland – accused him of being tainted by ‘national-Jewish ideology’.23 That Mark became director of the JHI at all underscores the lack of trained personnel among the Jewish Communists. For Mark, however, it was a chance for probation; he certainly did not want to fail.

JHI Publications during Stalinism

The politicization of the institute’s publications was in line with general developments in Polish historiography at this time. Shmuel Krakowski, head of the institute’s archive from 1966 to 1968, described the situation in the 1950s:

[U]ntil 1956 there was a quite stringent interference by the Party and others, and the course this took is called Stalinist. So it is natural that tight limits were imposed on Jewish – and not only Jewish – historians. But not only were certain limits imposed, which one was not allowed to exceed, there was also a certain language and methodology [...] I would even say a certain party dialect – with very harmful ramifications for scholarly work. Another method was to simply force historians to falsify history and accept certain non-existent facts in order to exaggerate the importance of the Communists. 24

The elements mentioned by Krakowski were typical of Polish – and not only Polish –historiography during the Stalinist period. This meant quoting frequently from Stalin’s and Lenin’s works, the use of Marxist- Leninist terminology, which often appeared artificial, and drawing a clear line between ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’ elements in history (Stobiecki 2007, 58 f.). Notably in works on the Second World War, the Soviet Union and especially the Red Army had to be praised as liberators and the Communists as the main pillars of resistance. Typical of the intensifying confrontation between the two power blocs were also commentaries on current political developments, such as the Korean War and the colonial conflicts.25

In its scholarly publications the JHI under Mark was under pressure to meet the political requirements. This was demonstrated in several ways. For example, in the Yiddish Bleter far geshikte translations of methodological articles by Soviet historians,26 such as Arkady Sidorov and Piotr Tretiakov, appeared, which emphasized the importance of Stalin’s works for historiography. Both had been members of a delegation to the Congress of Polish Historians in 1948.27 Szymon Zachariasz also submitted ideological articles to Bleter far geshikhte, among them a tribute to the life and struggle of Feliks Dzieryżyński, a non-Jewish Pole, who founded the Soviet secret police, the Cheka. Another emphasized the role of the KPP in the defence of Polish independence (Zakhariash 1951 and 1952). Neither article was related to Jewish history. However, the translations from Soviet scholars constituted a basic feature of East-Central European academia under Stalinism. They had also been published in Polish and many other languages spoken in the Soviet Bloc.28 Zacharisz’s contribution in turn served to emphasize the ideological reliability of the JHI and the fact that the institute was not drifting into ‘Jewish nationalism’. Equally, it was surely a concession by Mark to his critic Zacharisz.

The principles of Stalinist-style history writing were also applied to the institute’s own research publications. The communists in the ghettos were portrayed as the driving force of Jewish resistance. Uprisings in ghettos and camps were described as the Jewish contribution to the ‘great liberation war against German fascism’. The situation in the ghettos was described as a specific form of class struggle where the collaborators of the Judenrat suppressed the working masses and the resistance movement. On the Bialystok Ghetto Mark wrote: ‘There was a clear division [...] in the ghetto: Judenrat and resistance. There was [...] no compromise and no “third way” between these two forces, which were mutually exclusive’ (Mark 1952b, 4). The insurgents were, needless to say, ‘brought up in the best traditions of the workers’ movement, in the struggles of the KPP, in the revolutionary ideas of Marxism-Leninism’.29

The exaggeration of the communists’ role in the resistance is especially blatant if one compares Albert Nirensztein’s article on the resistance movement in the Kraków Ghetto, which appeared in the third issue of the Biuletyn, in 1952, and a publication of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, which had appeared six years earlier. In his article, Nirensztein claims: ‘There were two principal groups in the Kraków underground: the communist (then PPR) and the members of the Akiba; the latter recognized the indisputable political supremacy of the communists’ (Nirensztein 1952c, 184 f.). Referring to members of the underground movement, Betti Ajzenstajn described the situation somewhat differently. In The Resistance Movement in Ghettos and Camps, she writes:

The mentioned organizations [Akiba and the PPR] cooperated in a number of anti-German actions, despite the fact that there was huge ideological gap between them (which more than once produced frictions and disharmony) (Ajzenstajn 1946, 82).

The corrections, which aimed to harmonize history with the ideological foundations of the PZPR, also affected source editions, which made up a large part of Bleter far geshikhte, the Biuletyn and other JHI publications. The best known example is Emanuel Ringelblum’s notes from the Warsaw Ghetto. They appeared in a Yiddish edition in 1952 and as a Polish translation in the Biuletyn (Ringelblum 1952a).30 In both, passages critical of the Soviet Union or of Polish–Jewish relations were deleted, as well as references to religious aspects, Zionism and non-communist resistance. While data that emphasized the conflict between the Judenrat and the ‘Jewish masses’ did appear, other parts which did not fit the class-struggle paradigm were omitted, for instance, corruption in the house committees of the Ghetto. What was omitted, however, differed in the Polish and the Yiddish versions. This was especially true of what Ringelblum wrote about Poles attacking Jews, which was included in the Yiddish paper but not the Polish. But similar differences can also be found in cases that might have been disadvantageous from a Jewish perspective. While in the Yiddish version the collaboration of certain Jews with the Gestapo was noted, it was left out in the Polish version.31 In the introduction to the Polish version the editors – most probably Mark and Eisenbach – stated that ‘notes and expressions that were unclear or not significant for the topic of the research’ were omitted, 32 but to anyone willing to read between the lines, this was an indication that the significance for research might have been dependent on the political situation.

Another publication from the second part of the Ringelblum Archive, unearthed in December 1950, sparked a fierce debate within the Yiddish community and across the Iron Curtain (see below). This was Yehoshue Perle’s report ‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw]. Perle described the situation in the Warsaw Ghetto during the mass deportations in summer 1942 and harshly criticized the Judenrat and the Jewish police for assisting the Germans. He also criticized the victims themselves for their lack of resistance (‘Khurbn Varshe’ 1951, 101–40). Whether the text, which had been published anonymously as the author had not yet been established by the JHI’s researchers, had undergone a similar editing process remains unclear.33 It appeared roughly a year after it was found in late 1951 or early 1952, as the editorial introduction mentions the ‘American aggressors, who for seventeen months have been murdering the Korean people’.34

Such comments can be found in many JHI publications, as well as in other scholarly journals in Poland between 1950 and 1954. The introduction to ‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw] is an especially rich example, as it refers not only to the Korean War but also to the negotiations between German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Nahum Goldman, president of the World Jewish Congress, which began in December 1951 and would result in the Luxemburg Agreement in 1952 on reparations from Germany to Israel. In an allusion to this, the editorial mentions the ‘non-Jewish and Jewish agents of imperialism, who make pacts with yesterday’s Nazis [...] those who are repeating the traitorous politics of the Jewish councils’35 Elsewhere one can find critical comments on colonialism and discrimination against blacks in the United States (Mark 1951a, 25; Nirensztein 1952a, 184–89). In a similar vein, the exhibits in the JHI’s museum link the history of the Shoah and the Warsaw Uprising with a call for the struggle against imperialism (Rutkowski 1951, 127–29).

As we have seen, in the early 1950s JHI publications were punctuated with references to Marxist, and often more bluntly Stalinist, methodology and political biases. They had – especially in the case of sources – undergone a process of censorship in order to make them fit current political needs. While praise of Stalin’s genius and attacks on supposedly Western warmongers make these publications read like a caricature from today’s perspective, such a readiness to adjust the history of the Shoah to the party line was the only way possible for the JHI to publish its research at all36 and to make documents like those of the Ringelblum Archive accessible outside the institute.37

The JHI’s reception in the Yiddish world

Despite the ‘party dialect’ which dominated the publications of the JHI after late 1949, they continued to be read in the West, especially those in Yiddish. Mark’s earliest statements in the Yedies in November 1949 were closely monitored. The Wiener Library Bulletin (WLB) wrote in early 1950:

The recent far-reaching changes in the structure of Polish Jewish organizations, now taken over by nominees of the Government, are reflected in the journal of the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw [...] A programmatic statement makes it clear that from now on research will be proceeding exclusively along Marxist lines [... T]he tragic story of Polish Jewry, under German occupation in particular, is now going to be presented from the point of view of ‘class warfare in the Ghetto’.38

This was nevertheless a neutral description of the institute’s work in a non- Marxist Western journal. The WLB had committed itself never to comment on political matters. Even when Albert Nirensztein attacked the WLB and accused it of ‘only pretending to be progressive, while in fact they do not unmask the true sources and forces of the neo-Nazism in Western Germany, but abide by the principle of old, bankrupt bourgeois ideology’,39 the WLB did not respond. However, it vigorously refuted Nirensztein’s assertion that the journal would ignore research literature from outside the Western hemisphere. The dispute resulted not only in an exchange of letters,40 but finally in a comprehensive report on the JHI’s activity in the next WLB issue.41 This example shows that the JHI, despite its political comments or even attacks on Western institutions, was keen to stay in contact with such institutions, as it clearly sent all its available publications and detailed information to the WLB. It stands to reason that the main intention in criticizing the WLB in Bleter far geshikhte was to justify to the Polish authorities its subscription to the Western press.42

However, in the Yiddish press in the United States or Israel, the JHI could not count on the same sensibility the WLB showed. Distrust of Jewish scholars in communist Poland was deeply rooted on the other side of the Atlantic. This is not hard to understand considering anti-communist sentiment there at the time and the pro-American orientation of the vast majority of American Jews on the one hand and the anti-American propaganda, which infiltrated the institute’s publications, on the other. When in December 1950 the second part of the Ringelblum Archive was unearthed from the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, the news soon spread around the Jewish world. But while the London-based Jewish Chronicle reported the fact in almost neutral terms,43 in New York’s Morgen zhurnal Aaron Tseytlin’s commentary was far more critical. In his view, it would have been better if the material had never been found than falling into the ‘unkosher hands’ of Warsaw’s ‘Yevsec historians’, as it would only give them fresh material for their ‘absurd horror story that a class struggle took place behind the Warsaw Ghetto Wall’ (Tseytlin 1951). Similar comments could be found in Tel-Aviv’s Di naye velt, Arbeter-vort [The new world, worker’s word] from Paris, Ha-Dor, the mouthpiece of the Israeli Mapai Party or the Bulletin of the New York Jewish Labour Committee, as ‘Arkhivarius’44 lamented in Warsaw’s Yidishe shriften [Jewish scriptures]. It made him especially embittered that, as he wrote, the critics do not even wait for the publication of material in the Bleter far geshikhte before they start to criticize the supposed falsifications of the institute (Arkivarius 1951).45

However, even when Western reviewers read the JHI’s publications and attested to their scholarly value, it did not mean that they spared criticism of the institute. This can be seen in a review of Ringelblum’s Notitsn fun varshever geto [Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto], which appeared in the Bundist Lebns-fragn [Vital Issues], Tel-Aviv. For almost half the text the author, Eliahu Shulman, dwells on the fact that ‘the [Jewish] Historical Institute has been bolshevized – and the whole history of the Jews during Nazi occupation is falsified’ (Shulman 1953, 17). He even attacked the JHI’s researchers without exception. ‘After all, Berl Mark, Efraim Kupfer, [Artur/Aaron] Eisenbach and the other staff members of the institute are Stalinist slaves – and if their communist lord commands them to falsify – they will falsify’ (Shulman 1953, 18). However, his review of the book with Ringelblum’s notes was very constructive. Shulman called it authentic and a ‘principal historical and human document of the Ghetto period in Poland’ (Shulman 1953, 18).

The review gives a good insight into the misconceptions on the part of readers, or rather reviewers, outside the Soviet Bloc, who received publications on the Shoah produced at the JHI. In the political climate of the Cold War all publications from the other side of the Iron Curtain came under a general suspicion that they were falsified. Such falsification was perceived as a complete and willful distortion of the ‘historical truth’ in order to meet the political requirements of the Polish government and Soviet camp. This, however, was based not so much on a highly critical study of the JHI’s publications but on political – mainly anti-communist – convictions. However, the falsification of sources and the misrepresentation in historical interpretation functioned differently. The publications appeared within a framework of Stalinist academic methods, censorship, self-censorship and political control. Even so, there were no fixed boundaries on what could be written and published. The publication of a source that touched politically controversial or sensitive issues – as Ringelblum’s diary did – was unfeasible without deleting or editing those parts that obviously contradicted the political ‘truths’ of the day. The aim of such manipulations was not to send a politically correct message, but to get the writing published at all. Thus, they usually did not change the author’s overall intention and remained subtle enough that any such change was not immediately apparent.46 That is why, despite many changes, the text remained ‘authentic’ for Shulman and many others. His strident condemnation of JHI staff as ‘Stalinist slaves’ who falsified whenever they had to, however, shows his inability to acknowledge that an institution he regarded as politically hostile could nevertheless make a valuable scholarly contribution.

As mentioned above, another source from the Ringelblum Archive – ‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw] – sparked a debate in the Yiddish press in 1952. After the text, published in Bleter far geshikhte accompanied by a strongly politically biased editorial, reached the West, the Yiddish poet and journalist H. Leyvik bluntly accused the JHI of having fabricated the document. In his article in Der tog, he denounced ‘Khurbn Varshe’ as ‘blasphemous nonsense’ (Leyvik 1952).47 What angered Leyvik were the many accounts of the part the Jewish Ghetto police and the Judenrat played in the deportations. In his opinion, all Jews murdered in the Shoah were martyrs, while, as he passionately wrote, the author of ‘Khurbn Varshe’ depicted that ‘what took place in Warsaw was a thoroughly self-inflicted Jewish extermination’. 48 In his view, such a text, published in the Soviet Bloc and written by an anonymous author, must have been a forgery.49

Leyvik’s attack not only sparked a debate in the American Yiddish press,50 but also prompted a reaction from Mark himself. In a lengthy reply titled ‘Judenrat love of Israel’, Mark proved the authenticity of ‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw], referred to a similar account of the Jewish councils by Ringelblum and others in his group and identified its author as Yehoshue Perle, a well-known pre-war Jewish writer. In Mark’s view, Leyvik’s understanding of universal Jewish victimhood had the intention of whitewashing the Jewish councils and Ghetto police, thereby concealing ‘the internal treason in the ghettos’ (Mark 1952b, 114).51 In an allusion to the Luxemburg Agreement, Mark called Leyvick one of ‘all those in the United States, who require the rehabilitation of the Judenräte [...] for their current politics’ (Mark 1952b, 114).52 Mark’s article was not only a reply to Leyvik, it also addressed the Jews in Poland and served as another proof of its political correctness. Therefore, it was published not only in Bleter far geshikhte but also as a four-part series in the Polish Yiddish newspaper Folks-sztyme [People’s voice],53 which had a much greater readership among the Jews in Poland. Only a couple of months later, the Folks-sztyme text would play a role in the denunciation of Mark and the JHI.

The JHI – a threshold of Jewish nationalism in People’s Poland?

In autumn 1952 it seemed that late Stalinist anti-Semitism, with the Soviet campaign against rootless cosmopolitism and the imminent Slánský trial in Prague, was about to reach Poland. The fear that Warsaw too could become the venue of a show trial against a supposed Zionist conspiracy was escalating among the Polish Jews, and it was not unfounded. After Slánský had been arrested in late 1951, accused of leading a ‘Trotskyite-Titoist-Zionist’ conspiracy, the pressure on the Polish government to ‘uncover’ a Zionist conspiracy in its ranks increased. Although the Polish President, Bolesław Bierut, continued to resist such pressure,54 in November 1952 investigations within the power apparatus began. During these investigations, the Polish security service visited the JHI and took articles from the Western Yiddish press, written by high-ranking members of the state administration (Rayski 1987, 173–80). On 26 November, as the Slánský trial was coming to its conclusion, an employee of the Israeli Embassy was arrested, accused of espionage (Szaynok 2012, 219). All these events were not directly connected to the JHI. Nevertheless, Mark, who must have known that many of his former colleagues from the Soviet Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee had disappeared in the late 1940s, was well aware that the Institute and especially he himself could soon become a target in the search for Zionist conspirators. His worries proved well founded.

On 24 November, A. Sztark Wrocław, a correspondent of Folks-sztyme in Lower Silesia, obviously encouraged by the newspaper coverage of the Slánský trial, sent a hand-written letter and a densely typed eight-page report on the ideological foundation of the JHI to President Bierut. Sztark wrote that after lengthy consideration, he had decided it was his duty as a party member to inform him about the ideological transgressions of the JHI.55 In the report, however, it became clear that Sztark’s motivation was personal not political: Mark had reviewed and rejected a manuscript written by Sztark for the publishing house Yidish bukh [Jewish book]. The principal point of Mark’s critique was that the Jewish Council and its chairman were referred to in Yiddish terminology as Yidn rat and Yid elterer, which he considered was wrong, as Sztark quoted the opinion that ‘this institution was not Jewish but an enemy agency’.56 Sztark presented this to Bierut as proof of Mark’s ideological deviation: in his view, the Jewish councils had been as Jewish as the Pétain government in France was biased, both representing a certain sector of their respective societies.57

Referring to Mark’s answer to Leyvik in Folks-sztyme, he wrote:

The dispute between comrade Mark and the American Jewish reactionary H. Leyvik is limited to the following: while the reactionary Leyvik embraces all Jews murdered by the Nazi occupants with a holy Tallit [prayer shawl ...] Mark shows in his four articles mentioned above that the members of the Yidnrat and Jewish policemen in the ghettos were heinous traitors of the Jewish people, and this is why we have to denounce them and throw them out from among the holy Jewish Tallit. 58

Sztark thus accused Mark of adopting only a slightly modified model for interpreting the Shoah than Leyvik. In his view, a proper analysis of the class struggle in the ghettos would include the role of other bourgeois Jewish parties and non-communist actors. According to Sztark, Mark also ‘tries to featherbed the fight of Zionists against the communist resistance and reduces its importance’. 59 In his view, the most important task in the history of Polish Jews and Jewish ghettos in Poland during the Nazi occupation is to bring to light the full activity of Jewish bourgeois parties of all hues, with their clerical, Zionist and Bundist ideologies and their mercantilist, brutally egoist world views. They prepared the ground among the Polish Jews before the occupation and during the occupation they made millions of Polish Jews walk to the slaughter with their wives and children under the guidance of the Yidn-rat and without offering resistance, despite the heroic fight of the communists and the groups they mobilized. 60

Sztark accused Mark of being unable to correctly analyse the situation in the ghettos from a Marxist point of view and even more dangerous for the latter, of Jewish nationalist views and pro-Zionist sympathies. There is no doubt that he was aware of the serious implications this could have for Mark during a show trial against alleged Zionist conspirators in Prague.

Sztark’s attempt nevertheless failed to initiate a purge in the JHI. The office of President Bierut forwarded his letter to Szymon Zachariaz, who worked in the organizational department of the Central Committee of the PZPR and was responsible for Jewish affairs. Though Zachariasz had also been critical of Mark’s proximity to Zionist views in the past, he had decided to protect him. He replied to Sztark in a long letter, dismissing his critique in detail. Zachariasz however did add: ‘We don’t want to say that there had not been any mistakes in the works of the authors grouped around the JHI, including those of comrade B. Mark’, 61 but,

the publications [...] which have appeared in recent years are constantly aligning the old, false [political – St. St.] line [...] An important step forward in correcting the falsifying mistakes [falszywych bledow] will be the new work on the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which will appear on its tenth anniversary. 62

When Zachariasz wrote to Sztark – on 22 December 1952 – he was taking care that Mark’s new book on the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising would fulfil this promise. It is unclear how much Zachariasz told Mark about what was going on. The publications of Mark and the JIH, which appeared in spring 1953, however, are proof that he at least passed on the reality of a serious threat. Abruptly, in no time, the JHI had been added to the anti-Zionist propaganda of the Soviet Bloc, at least in its Polish publications. In the second issue of the institute’s Bulletin of 1952, which appeared in early 1953, the density of anti-imperialist key words, references to Stalin and Lenin and attacks on the ‘American supporters of the Jewish councils’63 and ‘the Zionist government of Israel [...] supporting the genocidal plans of the Anglo-American Aggression Bloc’ are apparent (Eisenbach 1952, 304). One article in the journal, F. Kupfer’s ‘On the Genesis of Zionism. A Contribution to the Problem: Zionism in the Service of Imperialism’, 64 was a condemnation of Zionism. From the correspondence between Mark and Szymon Datner, it becomes clear that Mark put pressure on his employees to introduce such phrases into their articles, 65 just as he was under pressure from Zachariasz and recent developments. On 13 January 1953 the Soviet News Agency TASS had announced the arrest of ‘murderer-physicians’ which, on behalf of the ‘foul Zionist espionage organization’66 Joint, had attempted to assassinate members of the Soviet government, 67 it alleged; the Warsaw Folks-sztyme reported the news on 14 January. 68 So Mark added Joint to the list of those to be attacked and included such an assault on Szymon Datner’s article, without the author’s knowledge or consent. 69 When Datner protested and demanded a correction in April 1953, he was immediately fired from the JHI with a note stating that, regarding his ‘ideological strangeness’, he was incapable of intellectual work. 70

Mark’s book on the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising had been copy-edited by Szymon Zachariasz and went to print on 15 January 1953, 71 two days after the doctors’ conspiracy had been made public. Its lengthy introduction not only contained portrait photographs of Stalin and Bierut, 72 it is also full of praise of Stalin, who, as the text suggests, almost single-handedly defeated Nazi Germany. At the same time it vehemently condemned Israel and Western Jewish organizations, especially the Luxembourg Agreement:

One of the most disgusting scenes [...] is the rehabilitation of the neo-Nazi regime of Konrad Adenauer by the World Zionist Organization, by the Jewish-nationalist organization Joint and by the reactionary government of the State of Israel. The leaders of global Zionism and the reactionary government of Israel desecrate the memory of six million victims, murdered by the genocidal Nazi murderers and disgrace the holy memory of the Ghetto insurgents, acting as lackeys of the American imperialists (Mark 1953, 12 f.).

Throughout the text all references to Zionist activists in the underground movement were deleted, even though they were known to Mark. In the Yiddish edition of the book, which appeared in 1955 and which has an identical structure, their names do appear, while the strident attacks on the Israeli government and the Joint, as well as the many references to Stalin and his character, disappeared from the Yiddish edition. It contains only one insignificant quotation from Stalin in the introduction (Mark 1955). 73

It seems that Mark intentionally withheld the Yiddish edition of his book until it became possible to publish it without anti-Zionist remarks, not least because the JHI’s contribution to the anti-Zionist propaganda of 1952–53 is restricted to its Polish publications. The last issue of Bleter far geshichte of 1952 does not contain any such statements. In order to express the JHI’s loyalty, it contains a Yiddish translation of Stalin’s article on economic questions (Stalin 1952). The article was obviously added to the issue only after typesetting had begun, since it uses Roman numerals in its pagination. The first issue of 1953 in turn is dedicated to a Yiddish translation of the minutes from the Warsaw trial of Jürgen Stroop, who had commanded the German forces during the Uprising. 74 It seems that Mark was attempting to withhold the anti-Zionist slogans of Western Jews, who did not understand the political situation in Poland at the time.

This is mirrored in the reaction of a foreign visitor to the JHI’s exhibition of the Uprising, which had also been reorganized in early 1953. The last part of the exhibition was meant to present the ‘ideological legacy of the insurgents’, which Adam Rutkowski, co-curator of the exhibition, characterized as ‘the hate of genocidal imperialism, the struggle for a free, powerful and independent People’s Poland [Polska Ludowa], the fight against warmongers for permanent peace’ (Rutkowski 1953b, 224). When in 1954 Ian Mikardo, a British Labour MP, visited Warsaw, he also went to the JHI. He described his tour of the museum for the Jewish Chronicle:

At the moment the two top floors at the Jewish Historical Institute are occupied by a magnificent exhibition recounting the story of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Uprising. When you get to the end of it there is a series of panels (which the director did not appear anxious for me to see) based on the theme that the post-war warmongers are behaving in exactly the same way as the pre-war warmongers. In juxtaposition with pictures of the Nazi leaders, Franklin Roosevelt, and Neville Chamberlain there are pictures of Eisenhower, Churchill, Ben- Gurion, and Sharett. The centrepiece is a mural representing ‘warmonger’ Harry Truman receiving the gift of a Sefer Torah from warmonger Chaim Weizmann. 75

Soon after Mikardo’s visit, and possibly even before his report in the Jewish Chronicle appeared, this part of the exhibition had been removed after a formal complaint by the Israeli embassy, because it had become ‘politically obsolete’ (Szaynok 2012, 266 f.). Taking Mikardo’s report into account, Mark was not unhappy about this. Indeed, when in the second half of 1954 the political situation in Poland was relaxed – the anti-Zionist campaign had stopped soon after Stalin’s death – politicized comments disappeared from the institute’s publications altogether. In the revised Polish edition of his book, which appeared in 1958, Mark even made a vague allusion to its political bias in the introduction: ‘However, the spirit of the time left its stamp on these works. Some insufficiencies and ground topics gave the works of 1953 and 1954 a certain one-sidedness’ (Mark 1958, 9).

Conclusion

There is surely no period in the history of Socialist Poland when history – and scholarly research in general – were more politicized and politically exploited than during Stalinism. Many of the writings that appeared in this period contained severe political distortions, which from the outside can even seem absurd. In Poland during the early 1950s, however, everyone, even those who had not been committed communists, knew how to read the texts, written in the ‘party dialect’ and sometimes containing ‘non-existent facts’, as Shmuel Krakowski put it. Even after Stalinism ended, Polish researchers knew how to handle texts written in this period. In 1957 the historian K. M. Pospiechalski from Poznań’s West Institute (Instytut Zachodni) wrote to Artur Eisenbach that for one of the publications, he wanted to refer to a passage from Eisenbach’s Hitlerowska Polityka Eksterminacja Żydow. However, since he suspected that Eisenbach would have written this passage differently now, after the end of Stalinism, he decided to ask him to, removing the strong political bias. 76 Readers outside Poland often did not know about the situation of Polish academia and lacked an understanding of the political demands placed on historical research. For that reason, the reputation of the JHI had been severely undermined by its publications of this period, which has been reproduced in historiography and even today compromises researchers like Ber Mark.

When evaluating the historiographic value of the JHI’s publications, the political circumstances should be taken into account. Despite many shortcomings and biases, these works are an important contribution to early Holocaust historiography. Without using classic Stalinist propaganda their works could not have been published. This is also true for important sources on the Shoah, originating in the Ringelblum Archive and other sources. Furthermore, if Mark and his colleagues had not adapted to the political situation, it would probably have placed the existence of the institute at risk. Without the JHI, however, its archives would have been uncertain and it is doubtful that they would have been made accessible to the public.

Acknowledgement

The research for this article was supported by grant no. 16–01775Y, ‘Inclusion of the Jewish Population into Postwar Czechoslovak and Polish Societies’, funded by the Czech Science Foundation.

Stephan Stach

Stephan Stach is a postdoctoral researcher and member of a research group at the Institute for Contemporary History of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague which is examining the reintegration of Jews into Czechoslovak and Polish society after the Second World War. He is currently preparing a monograph on the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw and knowledge about the Shoah between 1947 and 1989. In 2015 he presented his PhD thesis on interwar Polish nationality policy at Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg. He co-edited Gegengeschichte. Zweiter Weltkrieg und Holocaust im ostmitteluropäischen Dissens [Counter-history. Debates on the Second World War and the Holocaust in the dissent of East Central Europe] (with Peter Hallama, Leipzig, 2015) on the recollections of East and Central European dissidents.

ENDNOTES

1 The first was Leon Poliakov, Le Bréviaire de la haine. Le IIIe Reich et les Juifs [The harvest of hate. The 3rd Reich and the Jews] (Paris, 1951).

2 Inter alia on the role of the Wehrmacht, the exploitation of Jewish workers in the ghettos or on the Holocaust in the Reichsgau Wartheland, see Datner 1952, 86–155; Brustin-Berenstein 1953, 3–52; Dąbrowska 1955, 122–84; Pohl 2010, 165 f.

3 Eisenbach’s Hitlerowska polityka eksterminacji Żydów was based on his dissertation, supervised by Stanisław Arnold, chairman of the Marxist Historians’ Union.

4 See Dawidowicz 1981, 100 f.

5 Rose 2011, 184 f. Similarly, David Roskies ignores the political situation in Poland, calling Ber Mark a ‘loyal servant’ of the Polish communist regime, see Roskies 2012, 89.

6 On Poland, see Grözinger and Ruta 2008.

7 On the commission, see Jockusch 2012, 84–120; Aleksiun 2007, 74–97.

8 Archiwum Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego [Archive of the Jewish Historical Institute, hereafter AŻIH], signature 303/XX, folder 1, n.p.

9 On Ringelblum and Oyneg Shabbes, see Kassow 2007.

10 Such plans had already been launched by Philip Friedman in the early days of the commission, see AŻIH, 303/XX, folder 3, Statut Centralnej Żydowskiej Komisji Historycznej w Polsce przy Centralnym Komitecie Żydów Polskich [Statute of the Central Jewish Historical Commission at the Central Committee of Jews in Poland], § 6.

11 On the committee, see Grabski 2015.

12 AŻIH 303/I, folder 8, minutes of the board meeting of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland, 27 September 1947.

13 On the Jewish cultural life in post-war Poland, see Grözinger and Ruta 2008.

14 AŻIH, signature 310, folder 8, n.p., minutes of the JHI board meeting, 9 January 1948. The archive collection of the JHI is currently being reorganized. The files referred to in this text with the signature AŻIH 310 might now be found in another folder.

15 The title Bleter far geshikhte [Folios for history] is a reference to a journal edited by Emanuel Ringelblum before the war, which bore that title.

16 AŻIH, signature 303/1, folder 17, minutes of the board meeting of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland, 29 July 1949.

17 For more details on this period, see Stach 2008, 402–14.

18 ‘Undzere tsil’ [Our aims], Yedies: Byulletin fun yidisher historisher institut in poyln [News: Bulletin of the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland], November 1949, 1. The statement is not signed, however, there is little doubt that it was by Mark.

19 Ibid.

20 Sommer Schneider 2014, 244.

21 Kibbutz Lohamei haGettaot Archive, holdings registry 14859,6, Mark’s letter to Blumental and Kermisz, 30 September 1950.

22 Nalewajko-Kulikov 2010, 205–26, on the Soviet Union, 211–15.

23 Ibid., 218.

24 Interview with Stefan [Shmuel] Krakowski, Oral History Archives of the Oral History Department of the Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University Jerusalem (0050)0031, 7.

25 Such elements were also present in the exhibition at Auschwitz-Birkenau, see Hansen 2015, 208–22.

26 These were Sidorov 1950, 3–28; Pankratova 1950, 135–61; Tretiakov 1950a, 162–86 and Tretiakov 1950b, 187–97.

27 Górny 2011, 82.

28 Kwartalnik Historyczny [Historical Quarterly] published extensive digests of Tretiakov’s articles, regretting that these texts had already been published elsewhere in Polish; see Kwartalnik Historyczny 1950–51b, 3–12; Kwartalnik Historyczny 1950–51b, 13–38.

29 Ibid., 267.

30 In Polish ‘Notatki z warszawskiego getta’ [Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto], BŻIH, vol. 2 (1951), 81–208 and BŻIH, vol. 3 (1952), 46–83.

31 On the differences between the Polish and the Yiddish versions see Person 2012, 59–76, especially 70–4; Nalewajko-Kulikov 2013, 385–403.

32 Translation: Person 2012, 69.

33 The editorial introduction noted that the document could often not be deciphered; see ‘Khurbn Varshe’ 1951, 101.

34 As the Korean War was declared in late June 1950, the editorial must have been written in December 1951; ‘Khurbn Varshe’ 1951, 101, English translation, Rose 2011, 186.

35 Ibid. Contrary to Sven-Erik Rose’s assertion that the Jewish parties involved in the Luxemburg Agreement reiterated the policy of the Jewish councils, this was not unique to communist propaganda, but was widely used in Israeli politics, including by the political right parties; see Michman 2010, 316.

36 As Katarzyna Person points out, some of these publications are still the only accessible ones on these matters available in Polish; see Person 2012, 68.

37 The available English and French translations of Ringelblum’s diary are both based on the Institute’s Yiddish edition of 1952 and not on the more comprehensive and less censored edition of 1961–63. Furthermore, Jacob Sloan’s English translation (on which the French is based) contains many unnecessary errors.

38 ‘Jewish Historical Research in Communist Poland’, Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. IV, no. 1 (January 1950), 4.

39 Nirensztein 1952b, 169–75. Quote from the English abstract at XIV.

40 See criticism from the East, Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. VII, nos. 3–4 (May–August 1953), 16; ‘The Wiener Library Bulletin under Fire. Strictures in a Warsaw Learned Journal’, Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. VII, nos. 3–4 (May–August 1953), 127.

41 ‘The Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw’, Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. VII, nos. 5–6 (September–December 1953), 39.

42 A similar article appeared in the Polish Biuletyn, Rutkowski 1953a, 53–72.

43 It only briefly acknowledged that the material might have been distorted for political reasons; ‘The Warsaw Ghetto Archives. List of Traitors Found’, Jewish Chronicle (6 January 1951).

44 The pen name Arkhivarius was apparently used by one of the institute’s employees. It might have been Artur Eisenbach, then director of the institute’s archive.

45 Thanks to Agnieszka Żołkiewska for drawing my attention to this text.

46 Kermish (1953) and Blumental (1953) recognized the changes only due to their broader knowledge of the original. Both had taken part in the preparation of Ringelblum’s diary before their emigration from Poland in 1950.

47 English translation of the quote is from Rose 2011, 187.

48 Ibid., 209.

49 On the controversy, see ibid.; for a shorter but more balanced portrayal of Mark’s role in the dispute, see Schwarz 2015, 118–20.

50 For a discussion, see Rose 2011.

51 Translation: Rose 2011, 188.

52 Ibid., 188.

53 Mark, ‘Yudenratishe “ahaves yisroyl” (an entfer oyfn bilbl fun H. Leyvik)’ [Judenrat ‘Love of Israel’ (A reply to H. Leyvik’s Defamation)], Folks-sztyme, vol. 125 (6 August 1952), 127, (9 August 1952), 128, (12 August 1952), 129, (13 August 1952). The text appeared in both the journal Bleter far geshikhte and the newspaper Folks-sztyme under the same title. In Folks-sztyme it appeared in four parts.

54 Shore 2004, 42 f.

55 Archiwum Akt Nowych [Archive of New Documents – AAN], Komitet Centralny PZPR, Kancelaria Sekretariatu, 237/V-98, 73.

56 Ibid., 74.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid., 77.

60 Ibid., 78 f.

61 Ibid., 87.

62 Ibid.

63 Datner 1952, 153.

64 Kupfer 1952.

65 AŻIH, Szymon Datner, personal file, 76.

66 This description was used by Izvestiya in her article of 13 January 1953; Rapoport 1991, 79.

67 An English translation of the TASS statement can be found in ibid., 74 f.

68 Folks-sztyme, 14 January 1953.

69 AŻIH, Szymon Datner, personal file, 74.

70 Ibid., 79 and information supplied by Datner’s daughter, Helena Datner.

71 This date is mentioned in the imprint, see Mark 1953, 4.

72 Stalin is situated between pp. 8 and 9, Bierut between pp. 12 and 13.

73 The only Stalin quote is on p. 10.

74 The trial was held in Warsaw in July 1952 and ended with a death sentence, which was carried out on 6 March 1953.

75 Jewish Chronicle, 22 October 1954.

76 AŻIH 310/184AR, 201–300 K. M. Pospiechalski, letter to Eisenbach, 16 February 1957, n.p.

List of References

Ajzenstajn, Betti (1946) Ruch podziemny w ghettach i obozach. Materiały i Dokumenty [The underground movement in ghettos and camps. Materials and documents]. Kraków: Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna.

Aleksiun, Natalia (2007) ‘The Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland, 1944–1947’, POLIN, vol. 20, 74–97.

Arkhivarius (1951) ‘Notitsn fun an alten arkhivist’ [Notes of an old archivist], Yidishe shriften [Jewish scriptures], vols 10 and 11.

Blumental, Nakhman (1953) ‘Di yerushe fun emanuel ringelblum’ [Emanuel Ringelblum’s Legacy], Di goldene keyt [The golden chain], no. 15, 235–42.

Brustin-Berenstein, Tatjana (1952) ‘O hitlerowskiej metodzie eksploatacji gospodarczej getta warszawskiego’ [On the Nazi Method of economic exploitation of the Warsaw Ghetto], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego [Bulletin of the Jewish Historical Institute], no. 4, 3–52.

Conze, Eckart, Norbet Frei, Peter Hayes and Moshe Zimmermann (2010) Das Amt und die Vergangenheit. Deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik [The Ministry and the past: German diplomacy in the Third Reich and the Federal Republic]. München: Blessing.

‘Criticism from the East’ (1953) Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. 7, nos 3–4 (May–August), 16.

Dąbrowska, Danuta (1955) ‘Zagłada skupisk żydowskich w “Kraju Warty” w okresie okupacji hitlerowskiej’ [The destruction of Jews in the Wartheland during Nazi-occupation], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vols 13–14, 122–84.

Datner, Szymon (1952) ‘Wehrmacht a ludobójstwo (przyczynek do dziejów drugiej wojny światowej)’ [The Wehrmacht and the genocide (a contribution to the history of the Second World War), Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 4, 86–155.

Dawidowicz, Lucy S. (1981) The Holocaust and the Historians. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Eisenbach, Artur (1952) ‘O roli hitlerowskiego Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych w eksterminacji ludności żydowskiej’ [The role of the Nazi Foreign Ministry in the extermination of the Jews], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, issue 4, 289–304.

— (1953) Hitlerowska polityka eksterminacji Żydów w latach 1939–1945 jako jeden z przejawów imperializmu Niemieckiego [The Nazi policy of extermination of the Jews 1939–1945 as one of the manifestations of German imperialism]. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny.

— [as Azyenbakh, A.] (1955) Di hitleristishe politik fun yidn-farnikhtung in di yarn 1939–1945 vi an oysdruk fun daytshishm imperialism [The Nazi policy of extermination of the Jews 1939–1945 as one of the manifestations of German imperialism]. 2 vols. Varshe: Yidish bukh.

Gorny, Maciej (2011) ‘Die Wahrheit ist auf unserer Seite’ [The truth is on our side], Nation, Marxismus und Geschichte im Ostblock [Nation, Marxism and history in the Eastern Bloc]. Köln, Weimar and Wien: Böhlau.

Grabski, August (2015) Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce (1944–1950). Historia polityczna [The Central Committee of Jews in Poland (1944–1950). A political history]. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny.

Grozinger, Elvira and Magdalena Ruta, eds (2008) Under the Red Banner: Yiddish Culture in the Communist Countries in the Post-War Era. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Gruner, Frank (2008) Patrioten und Kosmopoliten. Juden im Sowjetstaat 1941–1953 [Patriots and cosmopolites. Jews in the Soviet State 1941–1953]. Cologne, Weimar and Vienna: Böhlau.

Gruss, Noe (1946) Rok pracy Centralnej Żydowskiej Komisji Historycznej [One year of the work of the Central Jewish Historical Commission]. Łódź: Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna.

Hansen, Imke (2015) ‘Nie wieder Auschwitz’ [Never again Auschwitz], Die Entstehung eines Symbols und der Alltage in einer Gedenkstätte [The emergence of a symbol and everyday life on a memorial site]. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag.

‘Jewish Historical Research in Communist Poland’ (1950) Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. 5 (January), 4.

Jockusch, Laura (2012) Collect and Record. Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Kassow, Samuel (2007) Who Will Write Our History? Emanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Kermish, Josef (1953)‘In Varshever Geto’ [In the Warsaw Ghetto], YIVO bleter [YIVOFolios], vol. XXXVI, 282–96.

‘Khurbn Varshe’ [The destruction of Warsaw] (1951) Bleter far geshikhte [Folios for history], vol. 4, no. 3, 101–40.

Kobylarz, Renata (2009) Walka o pamięć. Polityczne aspekty obchodów rocznicy powstania w getcie warszawskim 1944–1989 [The struggle for memory. Political aspects of anniversary celebrations of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 1944–1989]. Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej.

Kupfer, F. (1952) ‘O genezie syjonizmu. Przczynek do zagadnienia: Syjonizm w służbie imperializmu’ [On the origins of Zionism. A contribution to the problem: Zionism in the service of imperialism., Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 3, 73–85.

Kwartalnik Historyczny (1950–51b) ‘Znaczenie prac J. W. Stalina w sprawie językoznawstwa dla Radzieckiej nauki historyczniej’ [The meaning of J. W. Stalin’s works on linguistics for the Soviet Historical Sciences], vol. 58, nos. 1–2, 3–12.

— (1950–51a) ‘Historycy radzieccy o znaczeniu prac J. Stalina o językoznawstwie dla rozwoju nauk historycznych’ [Soviet historians on the meaning of J. Stalin’s works on linguistics for the development of historical sciences], vol. 58, nos. 1–2, 13–38.

Leyvik, H. (1952) ‘Tsvey dokumentn’, Der tog, 17 March.

Mark, Ber [Bernard] (1951) ‘Ruch oporu i geneza powstania w getcie warszawskim w świetle ostatnio odnalezionych materiałów Podziemnego Archiwum Getta’ [The resistance movement and the origin of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in the light of the newly found materials of the Underground Archive of the Ghetto], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 1, 3–26.

— (1952a) ‘Yudenratishe “ahaves yisroyl” (an entfer oyfn bilbl fun H. Leyvik)’ [Judenrat ‘Love of Israel’ (A reply to H. Leyvik’s defamation)], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 5, no. 3, 63–115.

— (1952b) Ruch oporu w getcie białostockim, samoobrona – zagłada – powstanie [The resistance movement in the Bialystock Ghetto, self defence – destruction – uprising]. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny.

— (1953) Powstanie w getcie warszawskim na tle ruchu oporu w Polsce. Geneza i przebieg [The uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto against the background of the resistance movement in Poland. Origin and course]. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny.

— (1955) Der oyfshtand in varshever geto [The uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto]. Varshe: Yidish bukh.

— (1958) Walka i zagłada warszawskiego getta [Struggle and destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej.

Michman, Dan (2010) ‘Kontoversen über die Judenräte in der jüdischen Welt. Das Ineinandergreifen von öffentlichem Gedächtnis und Geschichtsschreibung 1945–2005’ [Controversies on Jewish councils in the Jewish world. The overlap of collective memory and history writing 1945–2005], in Der Judenrat von Białystok.Dokumente aus dem Archiv des Białystoker Ghettos 1941–1943 [The Jewish council of Bialystok. Documents from the Archive of the Bialystok Ghetto 1941–1943], ed. Freia Anders, Katrin Stoll and Karsten Wilke, 311–17. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh.

Mikardo, Ian (1954) ‘The Jews in Poland’, Jewish Chronicle, 22 October.

Nalewajko-Kulikov, Joanna (2013) ‘Dzieje publicacji Kroniki getta warszawskiego w Polsce. Rekonesans badawczy’ [The history of the publication of the Warsaw Ghetto Chronicle in Poland. A scholarly exploration], in Lesestunde/Lekcja czytania [Reading time], ed. Grzegorz Krzywiec, Stephan Lehnstaedt, Ruth Leiserowitz, Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, 385–403. Warsaw: Neriton.

— (2010) ‘Three Colors: Grey. Study for a Portrait of Bernard Mark’, Holocaust. Studies and Materials. Journal of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research, vol. 2, 205–26.

Nirensztein, Albert [Nirenshtayn, Aaron, in Yiddish] (1952a) ‘A vikhtike dokumentatsye fun der neger-geshikhte in amerike’ [An important documention of Negro-history in America], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 5, no. 3, 184–89.

— (1952b) ‘Vegn “viner leybreri byuletin”’ [On the Wiener Library Bulletin], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 5, no. 4, 169–75.

— (1952c) ‘Ruch oporu Żydów w Krakowie pod okupacją hitlerowską’ [The Jewish resistance movement in Krakow during German occupation], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego (BŻIH), (January–June), vol. 3, 126–86.

Pankratova, A. M. (1950) ‘Di badoytung fun Y. V. Stalins artikeln vegn sprakhkentenish far der historisher vishnshaft’ The meaning of J.W: Stalin’s works on linguistics for the Soviet historical sciences], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 3, nos. 3–4, 135–61.

Person, Katarzyna (2012) ‘The Initial Reception and First Publications from the Ringelblum Archive in Poland, 1946–1952’, Gal-Ed, vol. 23, 59–76.

Pohl, Dieter (2010) ‘Die Historiker Volkspolens und der Judenmord. Erforschung und politische Instrumentalisierung’ [Historians of socialist Poland and the murder of the Jews. Research and political Instrumentalization], in Umdeuten, verschweigen, erinnern. Die späte Aufarbeitung des Holocaust in Osteuropa [Reinterpreting, keeping silent, remembering. The late coming to terms with the past in Eastern Europe], ed. Karol Sauerland and Micha Brumlik. Frankfurt and New York: Campus Verlag, 163–78.

Poliakov, Leon (1951) Bréviaire de la haine. Le IIIe Reich et les Juifs [Harvest of hate. The 3rd Reich and the Jews]. Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

Rapoport, Yakov (1991) The Doctors’ Plot. London: Fourth Estate.

Rayski, Adam (1987) Zwischen Thora und Partei. Lebensstationen eines jüdischen Kommunisten [Between the Thora and the Party. Life stages of a Jewish communist]. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder Verlag,173–80.

Ringelblum, Emanuel (1951) ‘Notatki z warszawskiego getta, cz. 1’ [Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, part 1], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 2, 81–208. — (1952a) Notitsn fun varshever geto [Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto]. Varshe: Yidish bukh. — (1952b) ‘Notatki z warszawskiego getta, cz. 2’ [Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, part 2], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 3, 46–83.

Rose, Sven-Erik (2011) ‘The Oyneg Shabes Archive and the Cold War: The Case of Yehoshue Perle’s Khurbn Varshe’, New German Critique, no. 112 of vol. 38, no. 1 (Winter) 181–215.

Roskies, David G. (2012) ‘Dividing the Ruins: Communal Memory in Yiddish and Hebrew’ in After the Holocaust. Challenging the Myth of Silence, ed. David Cesarani and Eric J. Sundquist 82–101. London and New York: Routledge.

Rubenstein, Joshua and Vladimir P. Naumov, eds (2001) Stalin’s Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rutkowski, Adam (1951) ‘Muzeum Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego podczas uroczystości gettowych’ [The Museum oft he Jewish Historical Institute during the Ghetto celebrations (meaning the celebrations of the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising)], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vol. 1, 127–29.

— (1953a) ‘O współczesnej burżuazyjnej Historiografii żydowskiej we Francji (O czasopiśmie “Monde Juif”)’ [Bourgeoise Jewish historiography in France (On the Journal Monde Juif [The Jewish World]), Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, no. 8, 53–72.

— (1953b) ‘Wystawa X-lecie Powstanie w Getcie Warszawskim’ [The exhibition‚ the 10th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, vols. 6–7, 218–33.

Szaynok, Bożena (2012) Poland–Israel 1944–1968. In the Shadow of the Past, and of the Soviet Union. Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation.

Schwarz, Jan (2015) Survivors and Exiles. Yiddish Culture after the Holocaust. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Shore, Marci (2004) ‘Children of the Revolution: Communism, Zionism, and the Berman Brothers’, Jewish Social Studies (new series), vol. 10, no. 3, 23–86.

Shulman, Eliahu (1953) ‘Emanuel Ringelblums tog-bukh’ [Emanuel Ringelblum’s diary], Lebns-fragn [Vital Issues], (May) 17f.

Sidorov, Arkady (1950) ‘Y. V. Stalin un di historishe visnshaft’ [Y. V. Stalin and historical science], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 3, nos. 1–2, 3–28.

Sommer Schneider, Anna (2014) Sze’erit hapleta. Ocaleni z Zagłady. Działalność American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee w Polsce w latach 1945–1968 [She‘erit Hapleta. Saved from the destruction. The activity of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Poland 1945–1968]. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka.

Stach, Stephan (2008) ‘Geschichtsschreibung und politische Vereinnahmung. Das Jüdische Historische Institut in Warschau 1947–1968’ [The writing of history and political appropriation. The Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw 1947–1968], Jahrbuch des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts [Yearbook of the Simon Dubnow Institute], vol. 7, 401–31.

Stalin, Yosif V. (1952) ‘Bamerkungen vegn di ekonomishe fragn, velkhe zenen farbundn mit der november–diskusye fun 1951 yor’ [Comments on Economic Questions of the November Discussion of 1951], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 5, no. 4, III–LXXXIV.

Stobiecki, Rafał (2007) Historiografia PRL. Ani dobra, ani mądra, ani piękna ... ale skomplikowana [Historiography in the Polish People’s Republic: not good, not smart, not beautiful ... but complicated]. Warsaw: Trio.

Szaynok, Bożena (2012) Poland–Israel 1944–1968. In the Shadow of the Past, and of the Soviet Union. Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej.

Tseytlin, Aaron (1951) ‘Di naye material fun varshever geto’ [The new materials from the Warsaw Ghetto], Morgen zhurnal [Morning Journal] (2 January).

‘The Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw’ (1953) Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. 7, nos. 5–6, (September–December), 39. The Jewish Chronicle (1951) ‘The Warsaw Ghetto Archives. List of Traitors Found’, 26 January.

‘The Wiener Library Bulletin under Fire. Strictures in a Warsaw Learned Journal’ (1953), Wiener Library Bulletin, vol. 7, nos. 3–4 (May–August), 27.

Tretiakov, Piotr (1950a) ‘Etlekhe fragn vegn der opshtamung fun felker in likht fun di shafungen fun Y.V Stalin vegn shprakh un shprakhkentenish’ [Some questions on the origin of peoples in the light of the Y. V. Stalin’s works on language and linguistics], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 3, nos. 3–4, 162–86.

— (1950b) ‘Y. V. Stalins arbetn vegn marksizm un shprakhkentenish un di oyfgabn fun di historiker fun altertum’ [Y. V. Stalin’s works on Marxism and linguistics and the tasks of historians of antiquity], Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 3, nos. 3–4, 187–97.

‘Undzere tsil’ (1949) ‘Undzere tsil’ [Our aims], Yedies: Byulletin fun yidisher historisher institut in poyln [Yedies: Bulletin of the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland] (November), 1.

Zakhariash, Shimon (1951) ‘Feliks Dzherzhinski – zeyn lebn un kamf (tsu zeyn 25-ter yortseyt)’ [Feliks Dzierzyński – his life and struggle (on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of death), Bleter far geshikhte, vol. 4, no. 2, 3–30.

— (1952) ‘Di KPP in shpits fun der farteydikung fun poylns umophengikeyt’, Bleter far geshikhte [The Communist Party of Poland in the vanguard defending Poland’s independence], vol. 5, no. 3, 3–31.

This article has been published in the fifth issue of Remembrance and Solidarity Studies dedicated to the memory of Holocaust/Shoah.

>> Click here to see the R&S Studies site

![Photo of the publication ‘The spirit of the time left its stamp on these works ’: Writing the History of the Shoah [...]](https://enrs.eu/media/cache/thumbnail_530_325/uploads/media/5b83b8959121a-zydowski-instytut-historyczny-lata-60.jpg)

![Photo of the publication ‘Purchasing and bringing food into the ghetto is forbidden’: Ways of Survival [...]](https://enrs.eu/media/cache/thumbnail_530_325/uploads/media/5c5c439495be8-bundesarchiv-bild-146-2000-009-04a-litauen-soldat-mit-juedischen-maennern.jpg)

![Photo of the publication The Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy: Cultural Activities and Zionist Propaganda [...]](https://enrs.eu/media/cache/thumbnail_530_325/uploads/media/5bb36b2566d7a-the-organization-of-the-jewish-refugees-in-italy-cultural-activities-and-zionist-propaganda-foto-2.png)

![Photo of the publication The National Socialist ‘National Community ’ in the ‘Foreign German Community [...]](https://enrs.eu/media/cache/thumbnail_530_325/uploads/media/5bb36f8ab018f-the-national-socialist-national-community-in-the-foreign-german-community.jpg)