The Loneliness of Victims. Methodological, Ethical and Political Aspects of Counting the Human Losses of the Second World War

Date and place: 9–10 December 2011, Buda Castle, Budapest

Organizer: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity, Berlin-Karlshorst German-Russian Museum in collaboration with the Institute of History of the Hungarian Science Academy

A conference on the human losses of the Second World War took place on 9–10 December, 2011, in Buda Castle, organised by the Berlin-Karlshorst German-Russian Museum and supported by the Institute of History of the Hungarian Science Academy. The conference was held in three languages, with simultaneous interpretation: English, Polish and Hungarian. (It is a mystery why German was not one of the official languages. Firstly, Germans had an important role as founders and main supporters of the initiative. Secondly, participants in the conference often talked to each other in German.)

In the introduction, Attila Pók, the host of the event, told participants that the aim of the conference matches that of the hosting institution, the Institute of History of the Hungarian Science Academy, in that, first, analysis should be preceded by solid empirical data collection, and second that local events should be interpreted in a wider regional or international context.

The organizing institution, the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity, was introduced by Rafał Rogulski. He said that the conference was the fruit of the co-operation of the German, Polish and Hungarian ministries of culture, joined by the Czechs and Austrians. The idea originated with Germany and Poland, who were also the main financial supporters of the event. The Network was founded in February 2005, and started operating in 2008. The organizational framework was formed in 2010, with the establishment of the Secretariat, which took on the coordinating and logistic tasks. The aim of the Network was connecting already existing research institutions, memorial sites, and NGOs. The institution supports the organization of conferences and exhibitions, and the preparation of scientific materials, translations, publications, and television and radio broadcasts. This conference was the third of its kind. The first one took place in Bratislava, and was themed around Memories of Central and Eastern Europe, while the second one took place in Warsaw, and was themed around the Genealogy of Central and Eastern Europe. Rogulski highlighted the fact that the aim of the initiative was not to divert focus from old crimes, or ignore memories, but to address the truth wholeheartedly, without causing harm to others.

Next, participants were greeted by Géza Szőcs, Hungarian Secretary of State for Culture. He said that he considered the counting of the victims of the Second World War important, because the European Union was born out of the fear caused by the horrors of the war, which makes all those victims pillars of the Community. The Secretary of State reminded the audience that there is uncertainty in Hungary regarding the numbers, and that this uncertainty is often exploited in popular politics. Were 450,000 or 600,000 people deported to malenkij robot? Did half of them return, or only a third? Were 450,000 or 600,000 Jews handed over to Nazis, and how many of those returned? How many prisoners of war died of hunger? During the war, how many people were killed by the occupying Germans? And by the liberating Russians? How many people became victims of ethnic cleansing? Secretary of State Szőcs also mentioned that the Second World War had more civilian victims than military. These were victims of air raids, epidemics, famine, retaliations, and expatriations. He also wished the participants a successful conference, but warned them that empirical data are not everything – subjectivity is just as crucial, because it can move people and make them realize how important each victim was. Richard Overy’s introductory presentation drew attention to problematic aspects of the conference topic. First of all, the exact number of Second World War victims is unknown to this day. Global estimates of 50–55 million are presumably incorrect, as the number of victims in the Soviet Union and China were considerably underestimated. The Soviet Union alone lost 27 million people, while China lost 16 million. These numbers exclude people who suffered irreversible physical or psychological damage, who are hard to count and therefore were never listed. One thing is alarming – the estimates vary considerably, from 50 to 80 million victims. One of the problems is that, in war, losses occur not only among well documented army troops, but also in unlisted civilian populations. (For example, does the death of an elderly, starved patient count as natural or as a result of poor war conditions?)

Overy also pointed out that militarized wartime communications considered the loss of civilians as natural and, what is more, expected the population to bear sacrifices, even in human lives. Another side effect of war is that people become hardened by conditions and develop a sort of moral numbness, which can often lead to atrocities and genocides. People can accept ideas that lead to the torture or extermination of the enemy, out of ideological, ethnic, or national motives. This is why new socio-psychological research focuses on the question: How can ordinary people become mass murderers? (The speaker did not mention it, but, based on this observation, it would be worth re-examining the causes of the indifferent behaviour of the civilian population during the persecution of the Jews.) And this is why, after the war, the re-establishment of moral and legal norms became a priority. He also mentioned that geographical areas under constant occupation or frequent change of authority were the worst affected. At the same time, he drew attention to other problems, such as unor poorly documented murders, which are hard to count later (for example, partisan combat actions or bombings). Counting is rendered difficult by other factors too, such as the high mobility in Europe at the time, the general fear of providing personal data, and the unintentionally or intentionally distorted memory of witnesses or perpetrators. In addition, German victims were not counted after the war. Official statistics are often unreliable, as evidence of war damages was manipulated by political propaganda, both during and after the war. One good example is the of Rotterdam in 1940, where official communiques spoke of 20,000 victims, whereas the real numbers were only 850–900. The most accurate data comes from Great Britain because, being an island, it was affected by considerably lower mobility, not to mention the fact that it avoided occupation. However, in many other places, there were no official registries, or there was secrecy. For example, the Auschwitz death lists were regularly destroyed. The exact numbers of victims from air raids were not revealed in order to avoid panic. Another obstacle to certainty is the fact that the political importance of this issue is still very high. For example, when the USA recently erected a memorial 175 of its soldiers who died in the Second World War, Bulgarians were outraged because the 1943–1944 bombing of Sofia resulted in 1,400 Bulgarian civilian victims. The bombing of Dresden is another notoriously politicized historical event. In the former East Germany it was considered to be imperialist aggression, aimed at intimidating the liberating Soviet Army, whereas in the former West Germany it was considered an unnecessary retaliation, as the war was already ending without it. As for historians in the West, some criticized it and some defended it, while others looked at it as a prelude to the Cold War. Based on propaganda data of the time, David Irving speaks of 135,000, and later of 250,000 victims. On the other hand, new research from 2010 speaks of 18,000–25,000 victims, which raised serious concern as it seemed to belittle the sufferings and sacrifices of Germans, as well as demeaning the tragedies of the Second World War. Others use the data to make claims for compensation to Germans. Overy also reminded participants that, from a moral point of view, there is no real difference whether there were 25,000 or 100,000 victims. Still, it is important that national memories not rest on false numbers. Nevertheless, another question is how one is supposed to remember people who have fallen victim to conquering powers. Overy said that certain political groups (the left and liberals) refuse to include such victims in the national memory. Furthermore, how is one supposed to remember people who fell victim to opposing forces – our own and their enemies? This dilemma is strongest in countries where the population was already deeply divided, like Ukraine, where more people died in the war than in the Holocaust, and the country suffered further losses under German and Soviet occupation. Another problematic aspect is that the Soviet Union killed its own people in the Gulag and through famine. Overy pointed out, referring to Other Losses by James Bacque (1989), that the death rate in prisoner-of-war camps in certain Western European countries was unusually high. In his final words, he referred to the fact that not only the dead can be considered victims, but survivors too (who were victims of torture, trauma, expatriation, confiscation of assets, prison, etc.), but they are never remembered in memorials. He emphasized the importance in research of professional integrity, which means that counting victims should not be a ‘competition’.

It is also important to remember that the Second World War had military as well as civilian victims. In new historical literature, especially in Italy, a new expression, ‘war victims’, is spreading, regardless who they were killed by, whether they were military or civilian victims, and which side they were on. ‘The motivation behind this new trend is that historians do not think in terms of good or bad, and they are not trying to serve justice in retrospect to one side or the other, but they are trying to count overall, common losses’, Overy concluded.

The next part was a press conference, where Attila Pók, Rafał Rogulski, Jan Rydel and Géza Szőcs briefly summarized the goals of the conference. Szőcs said that his presence testifies to the Hungarian government’s good intentions, which means it is welcoming efforts to discover facts about the recent past in an objective manner. In a decisive tone, he declared that ‘exact and credible facts are important so that public discussions do not drown in stupidity and lies’. He also said that every European country suffers from this phenomenon, whereas mutual knowledge of facts is the basis of reconciliation. Jan Rydel summarized the thematic diversity of the conference by categorising the presentations into three types. In the first group, the lectures dealing with significant numbers aim to banish political influence, and correct accepted but manipulated data (for example in Poland). In the second group, the lectures aim to define ‘victims’. In the third group, the lectures focus on certain case studies. Rogulski briefly informed journalists about the history of the organization, and also expressed his hope that more countries will join the network in the future. He also stressed that one of the main aims of the initiative is documentation of the facts.

Several questions were raised after the speeches. Regarding the questions about significant discrepancies in data, speakers tended to emphasize the role of false political motivations, and warned participants of their danger. For example, they mentioned that ‘Holocaust-relativist’ ideology stems from the fact that victim number estimates provided by Soviet troops liberating Auschwitz in 1945 (4 million in Auschwitz alone) were highly exaggerated, yet these figures were insisted upon for over 30 years, for purely political reasons. Another question dealt with the means of documenting and disseminating the findings the organization was using, and whether these findings will find their way into textbooks. From the response, journalists learned that the primary information method was the web page of the organisation (www.ENRS.eu), where all the materials would be available, at least in English, but possibly in every other participating language. In addition, the Network wanted to act as a supporter and coordinator of related public events (memorials, school information days, etc.). However, it is a long and winding road until findings find their way into textbooks – much of the research is still in an initial phase. Nevertheless, it is a promising sign that the work of the organization is supported by participating governments, which means that false information in current textbooks can be corrected. In the case of Hungary, it is true that textbooks are already being updated on the basis of recent empirical findings, although there is still room for improvement in the case of certain (mostly foreign-related) facts. One journalist focusing on the particularities of the Hungarian legal framework was trying to find out whether a conference dealing with victims of totalitarian regimes goes against a recently passed Hungarian law. In his response, Géza Szőcs said that he was not a lawyer and therefore could not give an accurate answer, but in his opinion, historical research based on empirical findings could not be against the law. (The law mentioned was Article 269c of paragraph 16 of the Penal Code, under the title ‘Public denial of the crimes of national socialist and communist regimes’, which reads: ‘Those denying, questioning or falsifying in public the genocide and other crimes against humanity committed by national socialist and communist regimes commit a crime and should be punished with a sentence of up to three years in prison.’) Regarding the same question, Szőcs emphasised that empirical scientific findings must be legitimized by public discourse in every case. Participants were also reminded that one of the key supporters of the initiative was Andrzej Przewoźnik, who tragically died in last year’s Smoleńsk plane accident, whose memory was preserved in an exhibition open until May 2012 in the House of Terror in Budapest, and then in Warsaw. Another key figure, from the German side, was Markus Meckel, last minister of foreign affairs of the former East Germany. In the first part of the conference, there were four presentations. The first two speakers talked about the number of victims in Russia, the third about those in Germany, and the last about those in Hungary. Vladimir Tarasov said that, in 1946, the Soviet Union acknowledged 10,845,546 Soviet victims (military and civilian together), which did not include Soviets who died outside the borders of the Soviet Union. An estimate in 1960 significantly corrected this number by putting estimates at 20 million. This estimate was widely accepted until the 1989 fall of the Soviet regime. In the past two decades, there was an increased need for more exact estimates. Comparing the 1939 and 1945 Soviet censuses, there is a difference of 37.2 million. From this number, demographers deducted people dying a natural death (11.9 million), and added the number of births (1.3 million). It added up to 26.6 million people unaccounted for by natural death. In the past few years, the Russian Ministry of Defence formed a committee, whose role it was to verify the number of 26.6 million victims. The speaker was a member of this committee, so his claims represented the official Russian position. The committee found the estimate of 26.6 million Soviet victims correct. Nevertheless, there were some grey areas, for example whether Nazi collaborators should be counted as victims. Tarasov said that they set up an online database of the dead and the missing, and they would also like to create a specialized national archive. Responding to a question, Tarasov also mentioned that there is significant research activity in Russia and post-Soviet states.

In his presentation, Boris Sokolov drew the attention of participants to the fact that previous Soviet data significantly underestimated the number of Soviet victims, which makes official counts unreliable. For example, in only German, Finnish and Romanian POW camps, over 4 million Soviet prisoners died out of the 6.3 million captured. This estimate includes those, who, in hope of liberation, joined the enemy and died in combat. In their case, the question is: Whose victims are they? Sokolov also pointed out that it is quite common for a victim to be claimed by more than one nation. (For example, Sub-Carpathian Hungarian soldiers forcibly enlisted in the Red Army are listed not only as Soviet victims, but also as Ukrainian, based on territory, and Hungarian, based on ethnicity.) Sokolov believed that it is impossible to tell the exact number of Soviet victims; estimates can only be made on the basis of demographic processes, statistics, and comparisons. According to his own research, actual Soviet losses are higher than the present 26.6 million estimate, and stand at 26.9 million. The victims were categorized by nationality in his publications, so he did not refer to them in detail in his lecture.

Rüdiger Overmans talked about the number of German victims. At the beginning of his presentation, he also pointed out that it is impossible to give final, exact numbers. Reasons for this include the lack of empirical data and vague definitions. For example, identifying German victims raises considerable problems. German Jews and expatriated Yugoslav Germans are a perfect example to illustrate that there are victims who are counted in several categories (for example, as German victims, victims of the Holocaust, and also as Yugoslav victims). Consequently, the number of victims of the Second World War cannot be established on the arithmetical basis of national statistics. In the past few decades, for example, German losses were estimated at between 3 and 9.4 million. It is questionable whether German victims should include Germans who fell victim to expatriation after the Second World War or German Jews, and to decide who counts as a German (those of German nationality, or of German ethnicity). Overmans said that victims of air raids were easy to count, but victims of ethnic cleansing and expatriation are not, although there has been extensive research in these areas. It seems certain, however, that previous estimates of expatriation victims at 2 million were an exaggeration, as in reality they rather numbered around 100,000–200,000. Focusing more strictly on the theme of the conference, participants learned that, according to the Wehrmacht’s own statistics, total military victim numbers were around 3.35 million, but this estimate excludes victims of the last few months of the war and POWs. By adding the latter two categories, Overmans counts 5.3 million military victims. Nevertheless, research is hindered by the lack of data sources, which was further aggravated by the fact that Soviet archives were closed to public inspection for a long time. For example, the former East Germany consistently blocked research of this sort, whereas the former West Germany wanted to identify every single German victim. Overmans pointed out that certain literary works (for example novels by Günter Grass) have had a significant role in forming the historical public consensus. However, historical science has to be able to provide credible data. Today, there are data collections that fulfil this criterion, and thus are used by hundreds of researchers. Nevertheless, more sponsors are needed to be able to continue the work.

Tamás Stark informed participants about the Hungarian situation. In his introduction, he said that the number of victims has been a political question for a long time. Typically, Second World War victims were not given memorials between 1945 and 1989, and Jewish victims could only be remembered in cemeteries. Soviet captivity was an obvious taboo. Military victims were overemphasised in textbooks, illustrating the cruelty of pre- 1945 fascist or fascist-friendly regimes. The question began to be properly answered in 1984, when Lajos Für, an agrarian historian, published an article in a daily paper estimating the total number of Hungarian victims at 1.2 to 1.4 million for the geographical area of the time. However, this was demographic speculation, based on data from before and after the war. Stark started methodically counting the victims in 1989. Based on his experience, we will never know the exact numbers, and our estimates will always produce worst and best case scenarios. Another important lesson is that most people become victims not of the war but of the governing dictatorial regime. The exact number of military victims in Hungary is estimated at 256,000, but documentation extends only to October 1944. This number includes 37,000 killed, 125,000 missing persons (some of whom were later found), 88,000 wounded, and 6,000 documented war prisoners. According to Stark, these latter numbers, together with military victims counted after the events of October 1944, add up to 100,000–160,000, of which 70,000 are known by name (these names were published in a book and are available online). Civilian victims total 45,000. Regarding the latter, the number of victims of the Yugoslavian ethnic cleansing is uncertain (10,000–20,000). The exact number of Holocaust victims also remains unknown, just as we do not know how many Hungarian nationals were affected by antisemitic laws. What is certain though, however, is that about 710,000 people of Jewish faith lived in Hungary in 1941. (It is important to note that Stark’s figures always refer to the geographic area of the time, which was about twice the present size.) We do not have exact survivor numbers either, as people who returned afterwards were always afraid of being persecuted, and so did not register. Based on all this information, Stark puts the total number of Hungarian victims of the Holocaust at between 440,000 and 560,000. Of these, 140,000 have been identified by name by the Hungarian Holocaust Memorial Centre (according to their website). Former prisoners of war make up another category. Soviet documents speak of 540,000, while Hungarian documents speak about 600,000 victims who were in captivity, including both soldiers and civilians. Of these, 420,000 returned alive, based on Soviet documents. However, Hungarian war prisoner registries started in July 1946 list only 220,000 people. As to people who returned before that time, there are only estimates. To sum up, the number of war prisoners who went missing in the Soviet Union was about 120,000–230,000. Of these, the Russian Federation acknowledges only 66,272, who were registered by name. However, these numbers do not include prisoners captured before 1944, people who died while being transported, prisoners kept in Romania, and probably those who died during epidemics at some point. Based on his research, Stark put the total number of victims at between 700,000 and 1 million, compared to a Hungarian population of about 14 million at the time.

In the second session on Friday, participants heard four more presentations. The first two concerned Polish victims. As an introduction, Łukasz Kamiński said that the official number of Polish victims of the Second World War, which was 6 million, was the result of a political decision. And although these numbers were later modified to 5 million in secret, official estimates stayed at 6,000,028. Furthermore, these numbers only included Polish and Jewish victims, and whether or not they included victims from the Soviet-occupied territories was not revealed. Katyn and the 1939–1941 deportations could only be mentioned in exile, and the 6-million estimate was never formally challenged. This symbolic number remained official even after the fall of the Soviet regime, but historians suggested that they should include victims of other nationalities and people from the Soviet Union. The reason for this was that different research projects (about Auschwitz, the Warsaw Uprising, and the deportations) indicated that the numbers from after the war were severely exaggerated. In 2009, historians published exact figures showing that the German occupation accounted for 5.5 million victims and the Soviet occupation for 150,000. The Poles consider it a moral obligation to identify every victim by name, a tremendous undertaking and one that, according to Kamiński, is more of an ethical than a scientific issue.

Mateusz Gniazdowski told participants that, in 2004, the Polish parliament asked the government to carry out an official survey of Polish war losses, in terms of both property and human lives, as a basis for compensation. The 2007 survey declares that the estimate of six million is only symbolic. Although a compensation office was established after the Second World War and kept official registries, the lists included only Polish and Jewish victims, and were closed in the spring of 1946 (which is important, because communist influence was limited at the time). Nevertheless, the occupiers probably tried to falsify the figures. In the end, the compensation office concluded that the total number of victims for the Polish territories of the time was 4.8 million (of which 1.6 million were unregistered, and thus uncertain). In addition, a demographic study found that some 1,225,000 thousand children were ‘unborn’ due to the war. These counts put the total number of Polish victims at 6,025,000. Following political orders, historians started to talk about 6,028,000 victims, which meant 22% of the population at the time. The numbers were not detailed. The final conclusion of the official research was that Poland lost the same number of people as the Jews. This was not true, but it helped to keep antisemitic feelings at bay. Research between 1949 and 1951 counted one million fewer victims, but the results were not made public. In 1970, it became evident that exact numbers would never be available, as too much data had disappeared or gone unregistered at the time, and historians accepted the official figure of 6,028,000 victims. Gniazdowski stressed that the Polish people will never know the exact numbers.

Peter Jašek informed participants about the Slovak situation. Describing the circumstances of the period in a schematic manner, he said that Slovak historians differentiate between direct and indirect (behind-the-lines) losses. Slovak military victims add up to 125,000 against the Soviets, 40,000 (!) against the Poles, and 18,000–22,000 (!) against the Hungarians. The Soviet figures include deportees. Against the Germans, from 2,000 to 10,000 died, out of an insurgent movement numbering 60,000. The number of people who died in exile and in partisan action was around 2,300. The speaker emphasized that the exact number of victims is unknown in many cases. The German occupation accounted for 5,300 civilian victims, whereas the Slovaks killed around 500 German collaborators. Exact Holocaust victim numbers are unknown, but it is sure that very few of the 70,000 deportees survived. Roma victims were around 311. The number of victims in the civil resistance movement against the Germans was about 2,000, while the number of people who died in the final stage of the war was about 7,000–7,500. Many people died in the Gulag. Air raids claimed some 1,000 civilian victims. From the above data, it is obvious that it is impossible to provide exact numbers, only estimates. By the end of the war, Slovakia had lost about 150,000 people. Putting together detailed name lists is the task of today’s historians, Jašek stated in conclusion.

Beata Halicka talked about the political exploitation of the ‘Eastern Documentation’ (on Germans expatriated after the war). According to her, it is unacceptable that, out of the approximately 11 million deported, exhibitions on the subject in the Historical Museum in Berlin mention only 2 million. She also highlighted the fact that Germans talk about Polish, Czech, and Yugoslav perpetrators, and the responsibility of Stalin, Churchill and Truman, but fail to mention what triggered the incidents. According to the speaker, this approach stems from reliance on the Eastern Documentation consisting of survivors’ testimony. Halicka questioned whether Germans can be considered as victims of persecution, and whether previous aggressors can subsequently be regarded as victims. (This question was answered by a clear “yes” from the audience.) The presentation, somewhat lacking in empathy, also questioned the credibility of witness statements. (Participants in the conference must have wondered whether this tone would be permitted in reference only to Germans, or to other nationalities as well.) The audience also learned that the number of victims was estimated at 2.2 million in 1958, at only 880,000 in 1977, and was never officially made public. In conclusion, Halicka stated that the 2 million German expatriation victims are a myth, just like the 6 million Polish victims. Her presentation evoked palpable unease in the audience. Overmans responded that the corrected estimates of the 1970’s were not kept a secret, as Halicka stated, but kept low key, in order to preserve peace in the Eastern bloc. (Here we note that it would have been useful to inform the participants about the data analysis at the beginning of the presentation.) Stark asked what expatriated Germans can be called, if not victims, and his question did not receive a proper response.

Friday closed with a presentation originally scheduled for Saturday. Its subject was victims of the Holocaust. Alexander Avraham introduced the ‘Names’ project of the Yad Vashem institute, which aims to identify victims by name. He said that the estimate of 6 million Jewish victims was made public at the Nuremberg Trials, and then disseminated and accepted worldwide. In reality, this number is only an estimate, and a high-end estimate. The real numbers must be between 5.1 million and 6 million. Yad Vashem has been counting victims and collecting names since its establishment in 1946. (From the presentation, it was not evident when the speaker meant victims who were dead and when he meant victims who survived. This vagueness of definition was typical of all the lectures.) Avraham told the participants that survivors and their families had been surveyed by questionnaires since 1956. The introduction of computers facilitated the creation of databases. They started digitizing their data in 1992. At present, the registry numbers 2,535,000 dossiers, 138,000 photos, and 6,440,200 names. However, some of these are inevitably duplicates, and the actual number is around 4 million. So far, only 250,000 have been processed. The database has been available to the public since 2004. The institute is planning to identify 4,700,000 victims by 2014. On the other hand, Avraham emphasized that registries only recorded people who were demonstrably deported. Other victims are harder to identify, as the perpetrators did not leave any official lists behind. The speaker also drew attention to the fact that it is extremely hard to filter duplicates, as names can be recorded in different forms. For example, the Berkovitz surname is present in 132 different forms, and Abraham in 137. As a result, the name Abraham Berkovitz can be written down in 18,000 different forms. The same thing applies to geographical names (Vienna, Wien, Bécs, etc.). At present, their database counts 4,305 first names in 141,894 forms, 90,049 family names in 372,287 forms, and 92,994 geographical names in 145,335 forms. As a consequence, the exact number of victims and all their names will never be known, but it is our moral responsibility to collect as many as possible. Responding to the questions, Avraham confirmed that those Jews who were fighting in the Allied forces, and were immediately executed by the SS upon falling into captivity, were not considered victims of the Holocaust, but military victims. However, the collection of their names is also under way.

Piotr Setkiewicz talked about the number of Auschwitz victims. As participants learned, the first victim number estimates were made by investigating units, based on witness testimonies, with the aim of prosecuting the perpetrators. Initial estimates put victim numbers at between 2 million and 6 million (or more). Even rumours circulating in the camp during the Holocaust referred to 4 million victims. More accurate research was hindered by the fact that documentation was destroyed by the perpetrators, who either refused to give statements or falsified their testimony. For example, Rudolf Hoess spoke about 2–3 million victims in Auschwitz, but only testified to 1.3 million at his trial. In the Nuremberg Trial, expert reports by the Polish government gave an estimate of 1.3–1.5 million. On the other hand, the Soviet Union was of an entirely different opinion, and tried to overestimate the number of victims. They tried to calculate the maximum killing capacity of the camp, which was 4,000 people per day. This led them to put total victim numbers for the duration of the war at 5 million. This data was made public in May 1945. The Soviets took into account the fact that the death factory could not operate on full capacity all the time, and thus regarded 4 million as a more realistic estimate. In the end, Rudolph Hess was charged with killing 2.8 million of these victims. The estimates based on capacity were problematic for several reasons. First, transport was not continuous, but occurred in waves. Second, as the crematoriums sometimes could not cope with the numbers, burning pits were also employed. Several measures were used to make the estimates more accurate, such as trying to derive estimates based on the amount of coal burned in the crematoriums, but coal was used not only to heat the crematoriums. Other researchers tried to base their estimates on the amount of Zyklon B used, but it was used for disinfection as well as killing. Furthermore, Zyklon B was not used exclusively until 1943. Some based their estimates on the changes in Sonderkommando numbers, which proved to be the least reliable method. Finally, the profession declared Franciszek Piper’s method the most accurate in the 1990s. Piper tried to determine how many people arrived in the transports, and how many were transported out. He concluded that out of the 1.3 million who arrived, 1.1 million died in the camp (out of which 1 million were Jews). However, we know that this estimate is not entirely accurate either, because many Hungarian Jews were unregistered or taken to labor camps straight away. The Piper estimates survived the storm, even in the light of documents which surfaced later. However, today’s historians would like to see the Piper estimates re-evaluated, and decreased by a few percentage points, but not greatly. Responding to questions, Setkiewicz said that the construction plans of crematoriums destroyed in the last few days before the allied invasion still existed, but the buildings are unlikely to be rebuilt at Auschwitz, in part due to Holocaust deniers, and will rather be preserved as they are. However, because it is possible to reconstruct the camp, scale models have been made, as well as visual reconstructions.

The chair, Judit Molnár added that between May and June 1944, 440,000 Hungarian Jews were deported, of whom 80 percent were killed in Auschwitz. This means that every third victim in Auschwitz was Hungarian.

The last presentation in this session was given by Robert Jan van Pelt. The speaker, who was trained as an architect, first became interested in the architecture of the death camps, and only later was drawn into the subject. He believes that it is justified to call Auschwitz the capital of the Holocaust, as out of the 1.6 to 1.7 million brought there, 1.1 million perished at the site. In his presentation, he referred to Holocaust denial; he was one of the expert witnesses at the trial of David Irving. Based on his account, Holocaust deniers all operate the same way. First, they try to discredit witnesses. For example, Irving testified that Auschwitz survivors tattooed themselves with registration numbers in New York, in order to qualify for compensation. This is not true, as the numbers can be verified systematically. Second, deniers argue that only Auschwitz should be acknowledged because other camps were destroyed. This is unacceptable from a scientific point of view. Furthermore, why would the perpetrators have insisted on destroying the evidence if no crime had been committed? Last but not least, why have Holocaust deniers claimed that the crematoriums did not have enough capacity to kill so many people? In conclusion, they are trying to deny the scope of the Holocaust, as Irving does. In his expert testimony, van Pelt concluded that up to 1.3 million people could have been killed in the crematoriums. On this basis, he examined how much time it would have taken to burn a body, how frequently the crematoriums would have needed to be reheated, how many corpses could have been transported in the lifts, and so on. Finally, he added that the capacity of the crematoriums, according to their factory manual, exceeds the estimated number of people who were burned in them. However, sometimes (as at the time of Hungarian deportations), they were used beyond their capacity.

In the first session of the second day of the conference, presentations focused on projects which aim to identify victims by name. In the first presentation, Dariusz Pawłoś informed participants about a database available on the www.straty.pl home page. The aim of the initiative is to register every Polish victim who died in during the 1939–1945 German occupation, and make the database available to the general public. The speaker said that they intend to explore events in detail, in a method similar to that used by historians researching victims among Parisian intellectuals. The project has been joined by 34 institutions (museums and archives) and 10 sponsoring bodies. However, the research has encountered certain problems, such as the fact that the former and present Polish borders differ, or that the database is not consistent, especially as researchers move further East in their work. The database includes military victims who fell in combat as well as POWs, members of the Polish underground movement, prisoners of German camps and ghettos, victims of the Holocaust, victims of some form of ‘peace protest’, victims of deportations, child victims, and people buried in unmarked graves. So far, three million victims have been identified by name, but these include duplicates, as some victims belonged to several different categories. In order to make the project widely known to the general public, it has even been advertised during daytime television and soap operas; according to the sharp rise in website visitor numbers, this was their most successful publicity strategy. The project collects data from several sources: through online and paper based surveys; through the integration of other, already existing databases, such as the one of Auschwitz victims; through the integration of data from other publications; and through data from all sorts of community surveys, such as a national competition for schoolchildren to discover family memories of the war (which was very successful). The speaker highlighted the interactive role of local communities. The project is supported by German institutions as well, and holds the Yad Vashem project in high regard. Responding to questions, the speaker said that the research started as early as 1945, but database building only became possible with the spread of computers. In addition, archives in the Eastern bloc only opened after perestroika.

Maciej Wyrwa introduced a project which aims to identify Polish victims of Soviet oppression. This database contains victims from the period 1939–1956 (1956 was the official date for the end of repatriation). Participants learned that the initiative started in the 1980’s, began to operate under the auspices of the Eastern Archive in 1988, and then moved to the framework of the Karta Centre. At present, the database numbers 860,000 entries, which have not been published for reasons of personal data protection. (It was not clear why victims of German terror are treated differently from victims of Soviet terror.) This project collects data from several sources, mainly from official archives (Soviet archives have been open to research since 1991) and online and paper based surveys. Results have been released in 20 publications, as well as in an online index that has been operating since 2001 and now includes 300,000 entries. The main aim of the program is providing data, organising memorials, gatherings, and exhibitions, and publishing.

Barbara Stelzl-Marx informed participants about a project that aims to identify Soviet army casualties who were buried in graves in Austria. We learned that Soviet military victims could be found in 200 graves in Austria, each marked by a red-starred obelisk. The most well known of these is on Vienna’s Schwarzenbergplatz. Ninety percent of the victims, or some 600,000 people, can be identified. Most died in combat (especially the battle of Vienna), and some in Austrian prisoner-of-war camps. The speaker highlighted the fact that the mortality among Soviet POWs in Austria was only 10 percent, whereas it was generally 60 percent elsewhere. Research is hindered by the fact that documents are written in the Cyrillic alphabet, which must be romanized. The aim is to integrate German, Austrian and Soviet lists, as well as to identify the resting place of each and every victim. Stelzl-Marx also spoke about the dismal state of the graves. After their victory, the Soviets exhumed POWs who died before 1945, and reburied them in central sites in Austrian cities. When the Soviets left, the graves were emptied again, and the victims reinterred in local Soviet cemeteries where they were given proper memorials. The speaker also informed participants that results of the research will be published in a bilingual (German and Russian) edition, and will be available on the internet.

Tadeja Tominšek Čehulić spoke about Slovenian victims. (His co-author, Vida Deželak Barič, could not participate in the conference.) The speaker used highly informative tables and charts to introduce their project on the number of Yugoslavian and Slovenian victims. The first lists, drawn up in 1964, included 600,000 Yugoslav victims, of whom 41,000 were Slovenian. This list was never made public. In the 1970’s, historians estimated the number of Slovenian victims at 65,000. According to today’s results, the official number is 97,506, with deaths recorded during and soon after the war (that is, taking account of post-war ethnic cleansing). Out of these victims, 31,714 died under German occupation, 6,415 under Italian occupation, 217 under the Hungarian occupation, 9,192 in partisan operations, 14,817 in ethnic cleansing after the war, 4,397 in so-called counter-revolutions, and 30,754 in other, unidentified circumstances. The speaker was part of a six-member group, which is also studying archives, military registries, and the relevant literature. We also learned that research is hindered by lack of access and financial difficulties. Information on the project is available on www.sistory.si.

In the second section, presentations focused on victims of the Holocaust in different countries. Judit Molnár informed participants about research in Hungary. She said that, within the borders of 1941 Hungary, the 14.7 million population included 800,000 Jews. Hungarian Holocaust researchers estimate the number of dead at 500,000–550,000. Eighty to eighty-five percent of the victims died in Auschwitz. We can thus conclude that about one-tenth of Holocaust victims and one-third of Auschwitz victims were Hungarian. The so called Jaross lists, which were made in Spring 1944, contained the names of 437,000 Jews slated for deportation. However, lists were not made everywhere, were not used by everyone, and included people who avoided deportation in the end (for example, by being taken to labour camps). Hungarian Holocaust victims include people who died in the Summer of 1941 in Kamenec-Podolsk; people who died during forced labour on the Eastern front (25,000–30,000); Jews killed in Novi Sad (1,000); people who committed suicide in Hungary or died when they were trying to flee; and people who were deported during the Arrow Cross regime, were shot on the banks of the Danube, or died in the ghetto. The project has been conducted by the Hungarian research group (of which Molnár is a member) of the Yad Vashem Institute since 1994. The research focuses on the period between 1938–1950, and collects every document that includes the term ‘Jewish’ or ‘Gypsy’. (The first anti-Jewish law was introduced in 1938, and people’s courts were closed in 1950.) Recovered documents are copied and sent to the Yad Vashem Center, where the data are analysed under the supervision of Kinga Frojimovics. The work will presumably have to continue for several more decades, under the present circumstances. The presentation was very comprehensive and informative, and also told the participants about future plans and tasks, but failed to give detailed information about concrete results and the database.

The second presenter in the session, Stefan Troebst, who would have talked about the Bulgarian Holocaust, had to cancel.

Alexandru Muraru’s presentation introduced the subject of the Romanian Holocaust through informative case studies. The speaker pointed out several antisemitic incidents that occurred during the Jewish expulsion from Bessarabia and North-Bukovina. Jews were thrown out of moving trains even as troops were withdrawing, and they also fell victim to pogroms in Dorohoi and Galaţi. While the violence on the trains was spontaneous, the pogroms were organized. Nevertheless, no one was held responsible, even after 1945. Military propaganda and rumours fostered the image of “communist Jews” and spoke of Jews welcoming Soviet troops and conspiring against Romanian troops. Such tales were untrue. However, they sufficed to prompt Romanian soldiers and civilians to take out their frustrations on the Jewish population. One comment from the audience mentioned a Polish instance of Jews welcoming Soviet troops as liberators, for which they were punished with pogroms.

Adrian Cioflanca’s presentation focused on data from the Romanian Holocaust. The speaker told participants that the number of victims was estimated at 280,000–380,000. Several factors account for the spread between the numbers. One of them is that official documents are unreliable, as they were often destroyed and falsified. In addition, some documents disappeared even after 1945, for example those used in people’s court trials. Communist narrative was equally distorted, either reflecting indifference or intentionally lowering estimates of the number of victims. Finally, the lack of access to military archives is another problem. Cioflanca illustrated his presentation with documents of the time, which proved that instead of the 500 victims mentioned in one set of official records, the actual figure was 14,000. Research after the fall of the Soviet Union started to provide more realistic estimates and to identify names where possible. Comments after the presentation informed participants about the fact that Romania established two committees, one on the Holocaust in 2004, and one on Communist terror in 2007.

In the last session on Saturday, Harald Knoll gave a presentation on a database on Austrian war prisoners of war who were deported to the Soviet Union, which is under preparation. The project started twenty years ago, with the opening of the Moscow archives. According to Soviet documents, 140,000–150,000 Austrians were taken prisoner, of whom only 120,000 were documented. Based on archives, about 7,000–20,000 people died or disappeared. The speaker pointed out that ongoing the project aims to inform the Austrian public about the location of their relatives’ graves and how they got there. Consequently, beside the list of victims by name, cemetery maps and documents of the time are equally important.

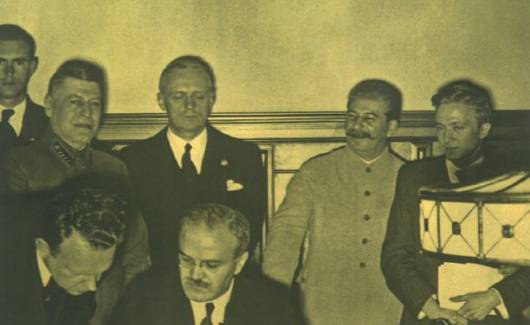

Aleksander Gurjanov’s presentation focused on Polish victims of Soviet occupation during the war, in great detail. He started with a definition of the word ‘victim,’ which made it obvious that it is not only the deceased who fall into this category, but also all victims of political persecution, such as those in detention or deported (which is typical of Russian practice). Most of these people survived the incidents. There is plenty of Soviet research material. The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs made detailed reports, which include extensive statistical data, all well documented and dated. It is remarkable that Polish victims of political persecution from 1939–1941 far outnumbered Soviet victims, when in general the Soviet Union persecuted its own citizens with great zeal. For example, out of the 370,000 people arrested on territory annexed to the Soviet Union by the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, 320,000 were Polish. The speaker also said that war prisoners are not normally considered victims of political persecution, but in the Polish case, doing so is justified. Soviet persecution of Poles during the Second World War counted more than half a million victims, of whom more than 60,000 died. The speaker also pointed out that these data were received unfavourably among the Polish public, as they gave an estimate only one-third as high as official Polish figures. The numbers can be verified by comparing lists with exact names, which is being done by a Russian-Polish joint research committee. The first results of this work indicate that the lists are not complete, as they include fewer names than either the Russian or the Polish estimates. However, calculations at this point indicate the correctness of the Russian estimates.

Marek Kornat opened his presentation by informing participants about the dispute in Polish history writing centred around whether the takeover of the eastern Polish lands by the Soviets should be considered as aggression or an act of undeclared war. He also pointed out that the Polish public thought at the time that there were between 900,000 and 1,600,000 million victims on this territory. Such views reflect significant exaggeration. In reality, around 42,000 POWs died, and 170,000 were deported. Polish publications still talk about 800,000 victims, even after the fall of the Soviet regime. However, the latest research puts the numbers much closer to Russian estimates. According to these, 1.8 million people fell victim to repression, of whom 320,000 underwent inhumane treatment and 150,000 died. The two most significant institutions involved in the research are the Polish Karta Institute and the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN). However, investigations have encountered uncertainties. Were all deaths documented? How reliable are Soviet documents? Finally, the speaker said a few words on one of the most significant grievances in Polish history – the interpretation of the Katyń events. In Polish public opinion, Katyń was not only considered a war crime but also genocide and a crime against humanity. The speaker said that even the Soviet Union acknowledged it as a crime against humanity in 1946, but only as long as the Germans stood accused. Kornat himself is uncertain whether Katyń was genocide, but insists it was a crime against humanity.

After the presentations by Gurjanov and Kornat, a heated debate broke out in the audience. The minimum number of Poles killed by the Soviets was at least 60,000. However, the Russians considered the upper estimate of 150,000 to be exaggerated, and pointed to possible overlaps (e.g. people forcibly enlisted in the Red Army). It is difficult to agree on the number of Polish victims because researchers carry out their analyses within different time frames (Who counts as war victim? Do post-war events count? Is the era of communist dictatorship included?), and because they work with different categories (for example, Poles forcibly enlisted in the Red Army are counted as Russian victims by the Russians, while Poles consider them victims of Soviet oppression, not to mention the fact that Russian researchers count civilian and military victims separately).

The last presentation was given by Łukasz Adamski, who raised the question: Where do victims belong? At present, some people are counted in different categories (mostly minorities, who are claimed by their mother country based on their geographical location and nationality). According to Adamski, the solution would be to count each victim based on their nationality. However, this was disputed by some participants, as Jews and Roma were killed based on their ethnicity, not their nationality, so it would be misleading to put them in the same group as those who fell victim to political persecution under occupation. Similarly, it is problematic to count a minority politician in opposition to the mother country as a victim simply on the basis of his or her nationality (for example, members of the Ukrainian Resistance did not consider themselves Polish, even if they lived under Polish authority).

At the end of the conference, participants engaged in a heated discussion. In his conclusion, Attila Pók said that all data which might be accepted today, but were once subject to political manipulation, should be re-examined. It is evident that victim numbers were overestimated in various cases. Based on general difficulties in research, it is not easy to provide the final and exact data for which the public clamours so adamantly.

Richard Overy added that it was sometimes the other way round, as victim numbers in the case of some groups were intentionally obscured and significantly underestimated. What is certain is that Polish textbooks need to be rewritten. At the moment, it is unclear under what criteria one can be considered a victim, and how people with multiple identities can be categorized. There is no disputing the fact that the last victims of the Second World War did not die at the time of the cessation of hostilities, but rather in the course of post-war retaliation and deportation. Overy also pointed out that it is not right to consider only dead people as victims. However, this makes the work of the statisticians even more complicated. Alexander Avraham’s conclusion was that there will never be final, exact numbers. The public has to understand that the number of victims can only be an estimate. One way to make such an estimate is to provide numbers at both ends of the scale, or rounded numbers that measure the whole scale. However, he warned participants of the dangers of correcting false numbers that are already embedded in public opinion too quickly, as they have a symbolic value that reaches beyond their exact magnitude. He also expressed approval of the fact that the Yad Vashem Institute considers survivors of atrocities as victims too, and collects data about them. New research has had many successes, but the work is not well coordinated and researchers often contradict each other or the facts. Avraham strongly opposed relativisation and encouraged the definitive separation of victims and perpetrators in the counting. (Participants were divided over this issue because, alongside innocent victims, there were many who had been sentenced to prison for serious crimes sometimes carrying the death penalty, who only enlisted in the army to save their necks; this means they were aggressors and victims at the same time, and so on.) Avraham insisted on a separate status for victims of the Holocaust, as they are victims of a different kind.

Tomasz Szarota thought it noteworthy that the research lacked comparative ambitions. For example, nobody has examined the reasons for the significant differences in death rates between different POW camps, or why the history of the Parisian resistance is so well documented when there is barely any information about the Warsaw resistance. Regarding Holocaust denial, he said that the Nazis realized in 1942 that the victims could not be left buried in the ground and that they needed to destroy this evidence of their crimes. This would seem to prove that they knew they were committing a grave crime. It is important to emphasize that there is a great difference in scale between the numbers of victims of the German and the Soviet invasions, and it can be affirmed today that the German invasion was the more serious. It is also unacceptable that today many Polish people think that at least there was law and order under German occupation, whereas the Soviets wreaked havoc and raped women. And it is totally absurd that it can be the commonly accepted opinion that the Germans were more humane because they killed their victims more quickly. (Nevertheless, two questions remained. First, if not only dead people count as victims, but also women who were raped and men who were deported, is it so certain that there was a big difference between the German and the Soviet invasions? Second, what Szarota referred to were Polish particularities.

In Hungary, the German invasion accounted for far fewer civilian victims when victims of the Holocaust were excluded. This is partly why the German invasion is seen so differently by victims of the Holocaust and their supporters, and by those were unaffected.) Szarota also pointed out that the Endlösung was a ‘final solution’ because previously the Germans were only trying to expatriate Jews from Europe. However, neither America, nor Palestine, nor the Soviet Union took in Jews. Finally, Szarota said that he would have preferred more mention at the conference of the victims of air raids.

The Canadian van Pelt found it strange that in Europe there is no shared celebrating, memory, culture, or identity.

Tarasov raised more concerns from the Russian side. Firstly, he noted the absence of representatives of several countries, such as France, Italy and the USA, without whom these questions cannot be debated in their entirety. He pointed to a lack of comparisons and conclusions from all the comprehensive and wide-ranging research. He was also disappointed that Russians were only considered as oppressors, while they were also victims and sufferers of the Second World War and Stalin’s regime. He pointed out that German and Russian occupation was on a different scale in the war, and German occupation was far more serious.

Rydel said that the main task should be to identify more of the victims by name, where Yad Vashem is doing an excellent work. Only after this can victims be categorized properly. (One understands that identifying victims by name and publishing them in comprehensive databases helps public reconciliation, and encourages peace between nations, but it is important to take into account that the only aim of such research projects, which take up a lot of money and time, is to serve political values. In different societies, there is varying demand for such a thing – for example, in Poland where, in the eyes of the public, every family is affected, the need is huge, whereas it is far smaller elsewhere. The scholarly value is far less significant, compared to the amount of work put in. Sometimes it even seems that these are merely exaggerated scholarly [?] reactions to today’s relativism and political demagogy.) Rydel also pointed out that the Soviet invasion more accurate.

According to Stark, a sharp distinction must be drawn between the different types of victims. Jews are victims of the Nazi Endlösung. People who died in air raids are victims of the war. It is more complicated, however, when we ask whether Polish deportation victims are victims of the war or of Stalin’s terror, or whether Sudeten and other minority Germans were victims of the war or of ethnic conflicts. Were Hungarians deported to the Gulag victims of the war or of the Soviet regime? Stark believes that perpetrators are equally varied. What is more, some perpetrators could later become victims.

The organizers of the conference concluded that, besides the war, totalitarian regimes should receive some attention in the future. Their victims, how they worked, and how they evolved. A general lesson of the conference is that research should be more harmonized, but it is evidently difficult to talk about painful memories of the past. The presentations at the conference will be published shortly, and the Network will continue its work, drawing conclusions. However, it is a fact that the participants represented only the countries that volunteered to take part in the conference, and thus gathered only selective research experience, despite the ambitions of the organizers.

Finally, let us draw a few conclusions ourselves. First of all, the speakers should have been warned that presentations involving a great many statistics should have made use of data projection in some form. The participants and interpreters would have appreciated fewer numbers, because data in rapid sequences are extremely hard to follow. Abbreviations of institutions, people’s names, and references considered normal by researchers are not necessarily known to ordinary audiences or among foreigners.

The organisers should perhaps have paid even more attention to detail than the speakers. First of all, it would have been useful to publish a short summary (maximum two pages) after each conference, summarizing its lessons in a short and comprehensible manner. This could then be sent to the press. This communication cannot be replaced by publishing the presentations or studies involved. In this case, the communiqué should briefly summarize difficulties of research (lack of data, unclear definitions), or let us know that the exact and final numbers will never be known, and only might still be surrounded by so many myths because the processing of the archives has only just begun. Regarding the latter, Korat pointed out that other research might provide information that helps make German data estimates can be given (so it is important to make clear whether numbers refer to a scale or give the extreme ends of a scale). Furthermore, it should be made clear that much of the data is politically motivated (with concrete examples), and provide estimates which are more up-to-date and seem more precise (including concrete examples). Finally, the websites of victim databases should be listed. In addition, the organizers could add a one page sheet with information about the organization. Without these, it is difficult to expect the press to give an accurate account of the conference.

In addition, the organizers should learn a few more lessons. First of all, two 9–10 hour long conference days are too exhausting. It might have made more sense to do the conference in three shorter days. Another remark concerns the advertising of the event. Among the audience we could not see university students, teachers, or members of the public. What is more, the profession might have been more broadly represented. (For example, it was rather surprising that the House of Terror from Budapest did not send anyone.) It might be worth considering that conferences that could be of interest to a broader public should be held in places that are more accessible to the public (e.g. university halls, not research institution conference rooms).

Simultaneous interpreting was an excellent idea, although the lack of German interpretation is incomprehensible and unjustifiable. It would be worth setting the bar higher for interpreters. Sometimes, participants felt that they were given only raw translations, or had to listen to a female interpreter with an unpleasant voice. Finally, it would be worth paying attention to the fact that the conference participants must be able to fit into the conference hall and not just the buffet. It is commonly assumed but not necessarily true that breaks are just as important at a conference as the presentations because they provide participants with valuable networking opportunities.

Rudolf Paksa, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Historian, Junior Research Fellow and Funded Research Assistant at the Institute of History of the Research Centre for the Humanities of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He received his PhD in 2012 with a thesis ‘The Hungarian Far Right Elite from the 1930s to 1945’. His research fields: Right wing extremism in the Horthy era; Modern Hungarian historiography; The history of the Eötvös Collegium (the first Oxford-style college in Hungary).

This article has been published in the first issue of Remembrance and Solidarity Studies.

>> Click here to see the R&S Studies site

![Photo of the publication Conference Report: The Loneliness of Victims. Methodological, Ethical and Political Aspects of Counting the Human Losses [...]](https://enrs.eu/media/cache/thumbnail_530_325/uploads/media/5c5ae6487fcdd-imgp6728.jpg)