Alles spontane Erinnern des Einzelnen wie der Gemeinschaft ist an Ereignisse gebunden, es ist selektiv, wertend und ichbezogen. Der Erinnerungsgehalt hängt schließlich vom geistigen Vermögen des Subjekts ab, von seiner Sensibilität und Einstellung, seinen Erwartungen und Vorurteilen. Folglich registriert die Erinnerung insbesondere das, was aus dem Rahmen fällt, was sich von dem Hintergrund scharf abhebt, das Subjekt überrascht und verwundert – mithin Ereignisse jenseits der Routine. Sie werden ausgewählt und in Hinblick auf ihre Wichtigkeit für das Subjekt hierarchisch geordnet. Festgehalten werden sie in der Gestalt, in der sie ursprünglich erlebt wurden, also auch mit der emotionalen Aura, welche ihre Wahrnehmung begleitete.

Drei Dimensionen der Erinnerung sind miteinander verflochten, die nur eine Analyse zu trennen vermag. Die kognitive Dimension, denn Erinnerung beansprucht die getreue Wiedergabe vergangener Ereignisse, ihrer Teilnehmer und Umstände, das heißt, eine wahrheitsgemäße Auskunft darüber, was einst geschehen ist. Die emotionale Dimension, denn die Wiedergabe vergangener Ereignisse weckt Gefühle, die diese einst begleiteten. Bei günstigen Bedingungen vermag sie sogar den sich Erinnernden in jenen Zustand zu versetzen, wie er von ihm damals erlebt worden ist. Die existentielle Dimension, denn erinnerte Ereignisse unterscheiden sich dadurch von den aktuell wahrgenommenen, dass sie auf besondere Weise mit dem sich erinnernden Subjekt verbunden sind. Sie vergegenwärtigen sich ihm als zu seiner Person gehörig, die unverändert dieselbe ist, damals wie jetzt. Solcherart bringen die erinnerten Ereignisse ihm die Dauer seiner Existenz zu Bewusstsein, die Veränderungen im ununterbrochenen Kontinuum der Zeit.

Die genannten drei Dimensionen sind auf die Vergangenheit, die Gegenwart und die Zukunft ausgerichtet. Auf die Vergangenheit, weil Erinnerung Auskunft darüber gibt, was einst wahrgenommen oder erlebt wurde und in seiner originären Gestalt heute nicht mehr vorkommen kann. Auf die Gegenwart, weil die von Erinnerung geweckten Gefühle jetzt, im Zuge des Erinnerns vergangener Ereignisse, erlebt werden. Schließlich auf die Zukunft, weil die Identität des Subjekts, welches sich erinnert, nicht etwas Gegebenes ist, sondern ein nach vorn offenes Projekt. Das schließt die Bereitschaft zur Veränderung ein, ohne jedoch mit der Kontinuität des eigenen Selbst zu brechen. Obwohl also das Gedächtnis Erlebtes und Antizipiertes enthält, charakterisiert es gerade als Gedächtnis die Fähigkeit, etwas festzuhalten, aufzubewahren und zu Bewusstsein zu bringen, was sich ereignet hat und vergangen ist.

Darum spielt auch die kognitive Dimension eine wesentliche Rolle sowohl in der Psyche des Einzelnen wie in der Kultur der Gesellschaft.

Das Gedächtnis ist aufs engste mit dem Raum, dem physikalischen wie sozialen, semiotischen wie gedanklichen, verknüpft. Das betrifft das innere hirnphysiologische Gedächtnis des Einzelnen wie auch das äußere, in diversen mnemotechnischen Hilfsmitteln – Inschriften, Bildern, Zeichen – fixierte. In noch stärkerem Maße gilt das wohl für das kollektive Gedächtnis, dessen Träger nicht nur Personen, sondern auch vergegenständlichte Formen sind: speziell dazu berufene Institutionen wie Museen, Bibliotheken, Archive, Einrichtungen der Denkmalpflege, Festkomitees für Jahrestage usw. Oder solche Institutionen, die sich im Rahmen ihrer eigentlichen Aufgaben auch damit befassen: Medien, Kirchen, lokale Verwaltungen und Ämter, Instanzen der Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur, das Militär, politische Parteien, Vereine, internationale Organisationen, die je nach Profil und Kompetenz Friedhöfe pflegen, archäologische Grabungen initiieren, denkmalpflegerische Maßnahmen, Forschungen der Historiker und Ethnographen veranlassen usw. Dazu gehören auch Instanzen, die darüber entscheiden, welche Personen und Ereignisse für würdig befunden werden, in den Schulbüchern oder anderen auflagenstarken Editionen und Formaten zu erscheinen, bzw. ob sie in Ritualen von lokaler, nationaler, europäischer oder, zumindest der Intention nach, universaler Bedeutung vorkommen. Alle diese Einrichtungen haben mit dem vergegenständlichten bzw. personalisierten kollektiven Gedächtnis zu tun.

Mithin ist das Gedächtnis in den physikalischen, sozialen und semiotischen Raum eingebaut, den es mit Bedeutungen und Bezügen zur Vergangenheit anreichert, wodurch diese sichtbar und abrufbar gemacht wird. Also ist der Raum auch einer des Gedächtnisses und deshalb, wenngleich nur partiell, auch Handlungsgegenstand des Politikers, der, auf Zukunftsgestaltung bedacht, diese auf die erinnerte Vergangenheit beziehen muss. Der Historiker wiederum, der die Vergangenheit erkennen will, muss die mit der Zeit abgelagerten Bedeutungsschichten einer kritischen Durchsicht unterziehen.

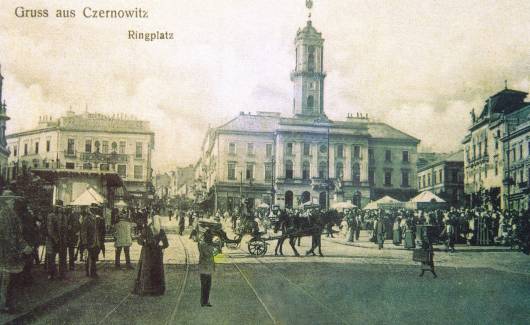

So wie der soziale Raum ist auch der Gedächtnisraum nicht homogen. Er enthält Erinnerungsorte, die nur in familiären oder lokalen Gemeinschaften mit einer bestimmten Vergangenheit assoziiert werden. Daneben auch solche, die dank eines langen und effektiven Wirkens von Institutionen mit Erinnerungen gesättigt sind, mit Erinnerungen großer Berufs- oder territorialer Gruppen, sozialer Klassen, ganzer Völker, von Anhängern einer Religion oder Ideologie. Das soll nicht heißen, dass jeder, der sich dazu zählt, diese Orte kennen müsste, sehr wohl aber kennt sie die Mehrheit derer, die diese Erinnerungen teilen; besonders jene, welche diese Gemeinschaft in ihren Augen repräsentieren. Solche Erinnerungen pflegt man, sie werden den Individuen auf verschiedene Art vermittelt und in Gegenständen wie in Riten aktualisiert. Orte, wo sich Erinnerungen bündeln, sind in der Regel Landschaften, in denen sich vermeintlich etwas Bemerkenswertes ereignete, oder Daten, an denen nach Meinung der Gemeinschaft etwas für sie Wichtiges geschehen ist. Schöpfungen der Natur oder des Menschen, die einst wie jetzt kollektive Emotionen wecken, die besondere Bande mit vorangegangenen Generationen symbolisieren oder die als Reliquien von Personen bzw. Ereignissen gelten, gleichviel ob sie mündlich, bildlich oder schriftlich überliefert sind – dies alles schlägt sich in Einstellungen nieder, die als konstitutiv für die Identität einer Gruppe, Klasse, Nation, einer religiösen oder ideologischen Gemeinschaft betrachtet werden. Es handelt sich um Zeichen von besonderer Bedeutung, die über lange Zeit und oft bis zum heutigen Tag der Gegenstand glühender Verehrung oder verbissenen Streits gewesen waren bzw. noch sind, und die deswegen Eingang ins kollektive Gedächtnis gefunden haben. Solche materiellen wie immateriellen Orte, an denen kollektives Gedächtnis sich mit besonderer Intensität manifestiert, nennt man Erinnerungsorte.

Jeder Erinnerungsort hat seine eigene Geschichte. Über Jahrzehnte oder gar über Jahrhunderte bildete er den Kristallisationskern für Ablagerungen aus Glaube und Gewohnheit. Man sprach und schrieb über ihn, vervielfältigte sein Abbild, behielt ihn je nach seiner Gestalt im Auge und im Sinn. Sein Schicksal weckte öffentliche Aufmerksamkeit, inspirierte den Meinungsstreit derer, die ihm Fürsorge angedeihen ließen, und jener, die ihn zu zerstören trachteten. Die verschiedenen Arten der Bedeutungszuweisung, die den Erinnerungsort konstituierten, sind dann mit Kalkül unternommen worden, wenn die Politik danach griff. Sie tat es, um sich selbst zu legitimieren, das heißt, sich einzugliedern in eine Reihe von Personen und Institutionen, deren Wiederbelebung bzw. Nachahmung eine maßgebliche öffentliche Meinung für einen Wert erachtete. Meist erfolgten solche Bedeutungszuweisungen jedoch spontan. Es ergab sich eben so, dass hier und nicht woanders Erinnerungen und Emotionen sich verdichteten und kultiviert wurden. Anfangs durch Einzelne, durch Familien, kleine Gruppen, später durch immer breitere Kreise, bis sie zum geistigen Eigentum der Allgemeinheit geworden sind und offiziell sanktioniert wurden.

Als effektiver als der Vorsatz des Staates erwiesen sich in der Regel die spontan unternommenen Schritte. So gut wie unbekannt sind Fälle, in denen ein von oben dekretierter Erinnerungsort länger am Leben geblieben wäre, als seine Urheber sich am Steuer der Macht halten konnten. Dagegen kennt man zahlreiche Erinnerungsorte, die ohne Unterstützung des Staates entstanden sind und nicht selten sich gegen den Willen der Machthaber behauptet haben. Das Gedächtnis ist äußeren Einflüssen gegenüber wesentlich resistenter, als man gemeinhin annehmen möchte. Diese oder jene „Geschichtspolitik“, die eine bestimmte Vergangenheitsversion oktroyieren möchte, welche der im kollektiven Gedächtnis gespeicherten widerspricht, erleidet früher oder später Schiffbruch.

Dies ist deshalb so, weil die meisten Erinnerungsorte das Wesen der Gesellschaft zum Ausdruck bringen, ihr symbolisches Eigentum und gemeinsames Erbe sind. Das zeigt sich in dem Schutz, den ihnen dazu berufene Institutionen gewähren, aber noch mehr in dem Glauben, welchen die Erziehung in der Familie dem Einzelnen einprägt, darüber hinaus die Schule, die Medien, Kirchen, Vereine und Ämter. Es ist der Glaube daran, dass Erinnerungsorte die Gesellschaft als ein kollektives Subjekt konstituieren, weil sie, Vergangenes vergegenwärtigend, die Gesellschaft verpflichten, es in die Zukunft hinüberzutragen. Dieser Glaube macht aus den Erinnerungsorten Exponenten kollektiver Identität, nicht die einzigen zwar, aber für die Gesellschaft, die sich darin selbst erkennt, besonders bedeutsame. Daher auch die erhöhte Sensibilität für das Schicksal jener Erinnerungsorte, die infolge von Kriegen, Bevölkerungsverschiebungen oder Grenzveränderungen in den Machtbereich eines anderen Staates gelangt sind. Näheres darüber später.

Gedächtniskonflikte

Fasst man einen bestimmten Zeitabschnitt ins Auge, erscheint die Topographie des kollektiven Gedächtnisses als Raum von Vektoren verschiedener Kräfte. Dazu zählen: das tatsächliche Ereignis der Vergangenheit – ob es sich zum Beispiel um Krieg, Revolution oder Umsturz, eine Epidemie oder Hungersnot, Massenvernichtung, Massenaussiedlung oder andere Kataklysmen handelt –, sowie der Wirkungsumfang und die Dauerhaftigkeit der Folgen des Ereignisses. Die Wahrnehmung dieser Fakten und Vorgänge durch den Zeitgenossen ist wiederum von Voraussetzungen abhängig, auf die sie beim Rezipienten treffen, also von gesellschaftlichen Stimmungen, Institutionen und kollektiven Überzeugungen. Einfluss nehmen weiter die Bedeutungen, welche die nachfolgenden Generationen vergangenen Ereignissen und Vorgängen zugeschrieben haben, wie sie gewichtet und in welche kausale Kette sie eingefügt wurden, ob sie als abgeschlossene, ruhende oder noch immer virulente Vergangenheit betrachtet werden. Hierbei kommt der aktuelle Zustand einer Gemeinschaft ins Spiel, ob sie sich gerade in der Phase des Aufschwungs oder des Niedergangs, der Schrumpfung oder der Expansion befindet. Beides beeinflusst die kollektiven Erwartungen, die ihrerseits die Vorstellungen von der Vergangenheit prägen: welche wertenden Akzente gesetzt werden, welcher Person man welche Rolle – Held oder Schurke – zuschreibt. Bestimmt ist diese Aufzählung nicht vollständig, sie gibt aber einen gewissen Eindruck von der Kompliziertheit des hier behandelten Phänomens und legt die Erkenntnis nahe, dass sich die Topographie des kollektiven Gedächtnisses mit der Zeit verändert, abhängig von den veränderlichen Faktoren, die ihr Gestalt verleihen. Aktuelle Erinnerungsorte können an Bedeutung verlieren, und andere treten an ihre Stelle.

Vor allem aber ändert sich die Topographie des kollektiven Gedächtnisses in Abhängigkeit vom Subjekt des Erinnerns. Je nach Gruppe oder Zusammenschluss von Individuen fällt sie anders aus, anders in jeder europäischen Nation einschließlich ihrer sozialen Gliederung in verschiedene Kategorien. Lässt sich von kleinen Gruppen sagen, dass ihr Gedächtnis homogen ist, weil der Druck auf die einzelnen Mitglieder so stark ist, dass sich die Erinnerungen einander angleichen und eine konvergente Aussage bekommen, so ist das bei großen Gemeinschaften anders. Deren Gedächtnis ist stets gespalten, oft in einem solchen Ausmaß, dass man sich fragt, ob wir es hier noch mit einem geteilten Gedächtnis zu tun haben oder nicht vielmehr mit zwei verschiedenen, nicht übereinstimmenden Gedächtnissen. Wider allen Anschein ist das keine bloß theoretische Frage. Die Antwort darauf entscheidet nämlich über unsere Einstellung zum gemeinsamen Gedächtnis; ob wir es als das Eigene betrachten oder nicht. Mithin darüber, wie unsere Einstellung zu anderen Gedächtnissen ist, wie viel Gemeinsames sie mit dem unseren aufweisen müssen bzw. was alles sie voneinander trennt. Und bildet das Trennende eine noch zulässige Abweichung oder schon einen unüberbrückbaren Gegensatz, so dass es unvermeidlich zur Konfrontation und dem zum Sieg einer der Seiten kommen muss? Es ist also eine politische Antwort, so wie die Antwort auf die Frage nach dem gemeinsamen oder geteilten Gedächtnis einer Nation oder Europas eine theoretische und politische zugleich ist.

Das kollektive Gedächtnis einer jeden Nation – nicht nur in Europa – umfasst verschiedene, sogar widerstreitende Erinnerungen, denn jede Nation erlebte scharfe, oft blutige innere Konflikte: Religionskämpfe, Bauernaufstände, Revolutionen, Bürgerkriege, Arbeitererhebungen, politische Zusammenstöße und Systemwechsel. Gelegentlich beendet ein Kompromiss solche Konflikte. Meistens jedoch hinterlassen sie Sieger und Besiegte, von denen jeder etwas anderes bzw. dasselbe Ereignis anders erinnert und bewertet. Diese Erinnerungen werden an die nachfolgende Generation weitergegeben. Ein gewaltsamer Konflikt geht nicht mit seinen Protagonisten zu Ende, er bleibt als Konflikt der Erinnerungen gegenwärtig. In dem Maße, wie die Nachgeborenen sich ihren Vorfahren verbunden fühlen, übernehmen sie deren Erinnerungen als wahr und machen sie zu Bestandteilen der eigenen Identität, so wie sie – mit den Familiengräbern beginnend – ererbte Erinnerungsorte übernehmen und pflegen. Mit der Zeit erlischt jeder Gedächtniskonflikt. Damit es aber dazu kommen kann, braucht es gewöhnlich Jahrzehnte sowie günstige Bedingungen, insbesondere muss alles vermieden werden, was den Konflikt neu entfachen könnte. Das Gedächtnis der polnischen Juden wäre mit dem Gedächtnis von Teilen der polnischen Öffentlichkeit nicht so zerstritten, hätte es den März 1968 nicht gegeben und nicht die Duldung des Antisemitismus in der „Dritten Republik“ (die Zeit nach 1989/1990 – der Übersetzer). Ob es eine Lösung des Gedächtniskonflikts geben könne, wenn dieser gereizt wird, darüber später. Jetzt genügt es festzustellen, dass jeder Versuch, mit den Machtmitteln des Staates das Gedächtnis einer Seite als ein gesamtnationales allen aufzuzwingen, in der Regel nicht das gewünschte, sondern ein umgekehrtes Ergebnis zeitigt. Der vermeintlich gelöschte Konflikt wird neu entfacht.

In abgewandelter Form beziehen sich obige Überlegungen auch auf das europäische Gedächtnis. Dieses wird von jenen in Frage gestellt, denen die Nation als höchste Form menschlicher Gemeinschaft gilt, zumindest in der Ordnung des irdischen Daseins. Aber selbst wenn Europa und ein europäisches Gedächtnis als real angenommen werden, bleibt die Frage, wie sich dieses zu den Gedächtnissen der Nationen verhält. Ist das europäische Gedächtnis lediglich eine abgeleitete Größe oder aber ein Phänomen eigener Ordnung? Ohne hier eine ausführlich begründete Antwort zu geben, genügt die Bemerkung, dass es sich um eine historische und politische Frage handelt. So lässt sich ohne weiteren Beweis feststellen, dass ein gemeinsames europäisches Gedächtnis nicht einfach auf die Vielzahl nationaler Gedächtnisse zurückführbar ist, wohl aber bleibt es dem Einfluss ihrer Konflikte ausgesetzt.

An solchen Auseinandersetzungen hat es nicht gemangelt. Die Gedächtnisse der Völker, insbesondere der Nachbarn, sind oft untereinander zerstritten. Dabei tritt jedes nationale Gedächtnis, obwohl innerlich gespalten, nach außen hin gewöhnlich als eine Einheit auf. Die Tatsache allein, dass jede Nation ihre eigenen Erinnerungsorte besitzt, muss noch keine Konfliktquelle darstellen. Nun war aber die Vergangenheit angefüllt mit Kriegen, und diese hinterließen Sieger und Besiegte, verursachten menschliches Leid, Zerstörung und Raub von Kulturgütern, materielle Verluste, Grenzverschiebungen und Umsiedlung der Bevölkerung. Als Folge davon ergab sich, dass dieselben Objekte, Territorien oder Städte von verschiedenen Nationen als ihre Erinnerungsorte eingefordert werden. Wenn jede Seite dabei Ausschließlichkeit beansprucht und im kollektiven Gedächtnis hauptsächlich des eigenen vom Nachbarn und Rivalen zugefügten Unrechts gedenkt, dann ist der Konflikt unausweichlich. Er kann insbesondere dann scharfe Formen annehmen, wenn das Gedächtnis auf beiden Seiten zum Objekt politischer Manipulation gemacht wird. Dann ist es möglich, dass der Gedächtniskonflikt sich in einen realen Konflikt verwandelt, dass das auf beiden Seiten längst beruhigt geglaubte Gefühl existentieller Bedrohung und gegenseitiger Feindschaft zu neuem Leben erweckt wird. Und damit wird ein alter Hader in neuer, aber ebenso grausamer Gestalt wie sein Urbild aufgefrischt. Es genügt an den Zerfall Jugoslawiens zu erinnern, wo der sorgfältig gepflegte und entsprechend angeheizte Gedächtniskonflikt in Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit mündete.

Gedächtniskonflikte haben auch andere Ursachen. Die Geschichten der europäischen Völker sind so miteinander verquickt, dass jede einzelne von ihnen nur ein Element des größeren Ganzen bildet. Viele Gestalten, Ereignisse und Prozesse sind mehreren Nationen zugehörig, manche sogar allen. Aber diese gemeinsamen Gedächtniselemente werden oft mit umgekehrten Vorzeichen versehen. Die Helden der einen Nation gelten in der anderen als verdammt. Was hier als Sieg gefeiert wird, wird dort als Niederlage beklagt. Die einen betrachten sich ausschließlich als Opfer, während andere in ihnen Unterdrücker, wenn nicht gar Henker sehen. Jenseits der Grenze ist von rechtloser Aussiedlung die Rede – diesseits vom Vollzug internationaler Beschlüsse. Was die einen als nationale Katastrophe erinnern, ist für die anderen die Befreiung von fremder Übermacht. Die Aufzählung ließe sich mühelos fortsetzen. Auch solche Konflikte können politisch instrumentalisiert werden, und zwar durch Kräfte, die damit ihre materiellen oder symbolischen Ansprüche zu rechtfertigen oder – was gefährlicher ist – das nationale Gedächtnis zu homogenisieren und in solcher Gestalt den Mitbürgern aufzuzwingen versuchen. Der nach außen gewendete Gedächtniskonflikt soll dann den internen ersticken; ein äußerer Feind wird aufgebaut, gegen den Geschlossenheit, Stärke und Kampfbereitschaft aufgebracht werden müssen. Autoritäre und totalitäre Bewegungen benutzen immer wieder diese Art Soziotechnik, um gesellschaftliche Unterstützung zu gewinnen.

Was macht man mit Gedächtniskonflikten, die sich als virulent erweisen? Lässt sich für sie eine Lösung finden, die den Ursprungskonflikt nicht einfach reproduzierte, aber zugleich vermiede, dass er vergessen oder durch ein rückwärts projiziertes fiktives Einvernehmen zugedeckt wird? Es ginge also um eine Lösung, die den Protagonisten erlaubte, die je eigene Erinnerung zu bewahren, sich nicht zu verleugnen und das Zusammenleben mit der Gegenseite dennoch zu ordnen, so dass die Andersartigkeit der nicht übereinstimmenden Gedächtnisse gemeinsam akzeptiert würde. Dies erschwerte die Umwandlung der Unterschiede in einen gewaltsamen Streit oder machte einen solchen gar unmöglich. Bevor ich eine Antwort versuche, gilt es festzuhalten, dass die bloße Fragestellung bereits eine Folge politischer Entscheidungen ist, nämlich ob wir einen Gedächtniskonflikt schlichten wollen oder wenigstens alles unterlassen, was ihn schüren und das ohnehin angespannte Verhältnis zwischen den Seiten verschlechtern könnte. Selbstverständlich ist eine solche politische Entscheidung keineswegs. Eben noch war von Kräften die Rede, die an einer für alle Beteiligten annehmbaren Perspektive der Konfliktlösung gar nicht interessiert sind, oder nur insofern, als sie es für notwendig erachten, sie zu bekämpfen. Sie suchen die radikale Entgegensetzung des Eigenen dem Fremden, des Freundes dem Feind. Das Verhältnis zu den Trägern anderer kollektiver Gedächtnisse fassen sie in Kategorien der Konfrontation und streben danach, den eigenen Standpunkt gewaltsam durchzusetzen. Darum wiederhole ich: erst eine politische Entscheidung, die andere Seite nicht als Gegner, sondern als Partner auf der Suche nach Verständigung zu betrachten und somit eine Verständigung für möglich zu halten, lässt die Suche nach dem besten Modus der Verwirklichung sinnvoll erscheinen.

Drei Dimensionen der Gedächtniskonflikte

Gedächtniskonflikte sind deshalb so schwer zu lösen, weil alle Erinnerung Ausschließlichkeit darüber beansprucht, was tatsächlich geschehen ist. Wenn also zwei Gedächtnisse über ein und dasselbe Thema verschiedene, unversöhnliche Meinungen festhalten, erscheint die Lage aussichtslos. Sie ist es aber nicht, denn die Seiten können eine beiderseits anerkannte Autorität anrufen, der sie den Schiedsspruch überlassen. So ist man über Jahrhunderte verfahren. In der Neuzeit indessen entdeckte man, dass sich der Streit um die Vergangenheit kognitiv noch anders entscheiden lässt, nämlich indem man das Feld der Erinnerungen räumt und die Dienste der Geschichtswissenschaft in Anspruch nimmt. Als Wissenschaft im neuzeitlichen Verständnis ist die Geschichte nicht länger eine Aufzeichnung des Gedächtnisses, was sie die meiste Zeit davor gewesen war. Sie ist vielmehr in der Lage, über die bloße Vergegenwärtigung der Vergangenheit in den Erinnerungen hinauszugehen und Vergangenes unabhängig vom Gedächtnis zu erkennen, und zwar mit Hilfe von Quellen, der Überlieferung aller Art, die auf uns gekommen ist. Quellen lassen sich so erforschen, dass aus ihren Merkmalen Rückschlüsse darüber zu gewinnen sind, wodurch und unter welchen Umständen sie ihre ursprüngliche Gestalt erhielten und welchen Veränderungen sie später unterlagen.

Auf die übrigens schon oft beschriebenen Einzelheiten kann ich hier verzichten. Es genügt festzuhalten, dass das historische Wissen Informationen über die Vergangenheit bereithält, die außerhalb der Grenzen des Erinnerungsvermögens liegen, was von beider Unabhängigkeit voneinander zeugt. Damit ist das Verhältnis von Geschichte und Gedächtnis aber nicht ausgeschöpft. Wesentlich für die geschichtliche Darstellung der Vergangenheit ist eine Perspektive, die anders als das Gedächtnis eine Identifikation des Historikers mit dieser oder jener Gestalt, mit den Protagonisten vergangener Konflikte ausschließt. Der Historiker als Historiker hat nicht Partei zu sein. Er hat lediglich die Partei seines Faches und seiner Forschungsdisziplin zu ergreifen. Mit anderen Worten, zu seinen Pflichten gehört es, voll und ganz die ethischen und kognitiven Normen zu verinnerlichen, die sein Verhältnis zum wissenschaftlichen Fachmilieu und zur breiten Öffentlichkeit regeln. Damit bekommen seine Forschungsinitiativen eine Orientierung, mit der sie und ihre Ergebnisse der Fachkritik standhalten und danach für die breite Öffentlichkeit Gültigkeit erlangen können. Das verlangt ein vollständiges Einvernehmen mit den Auffassungen des Fachmilieus über das Vorgehen und die Bewertungskriterien der angewandten Verfahren wie über die Gültigkeit des auf diesem Weg erlangten Wissens.

Vollständiges Einvernehmen ist in Wirklichkeit selten, Abweichungen vom idealen Muster braucht man nicht lange zu suchen. Lassen wir die Unzulänglichkeiten des Handwerks, der Konzeption oder Schreibweise einmal bei Seite, gefährlicher erscheint da die Untreue mancher Historiker ihrem fachlichen Ethos gegenüber. Sie führen die Öffentlichkeit in die Irre, indem sie für Geschichte ausgeben, was in Wahrheit eine Gedächtnisaufzeichnung ist. Das heißt nun nicht, dass es dem Historiker nicht gestattet sei, diese zu registrieren. Im Gegenteil. Es gehört unter anderem zu seinen Aufgaben, Quellen zu erschließen, indem er Erinnerungen von Personen fixiert, die aus psychischen oder sozialen Gründen dies selber nicht tun können. Es ist jedoch zweierlei, Erinnerungen zu bewahren oder diese für Geschichte auszugeben, damit würde nämlich einem Bild der Vergangenheit, das unweigerlich selektiv und parteiisch ist, allgemeine Gültigkeit zugesprochen. Besonders häufig unterläuft dies Zeithistorikern, die stärker als andere dem Druck politischer Institutionen und der Medien ausgesetzt sind. Diese verlangen von den Historikern, dass sie sich mit einer Seite eines vergangenen Konflikts identifizieren und ihn entsprechend einseitig darstellen. Damit ist nicht entschuldigt, wer solchem Druck nachgibt, denn manche wissen sich dem zu widersetzen. Es zeigt aber eine allgemeine Regel, dass es die Geschichte umso schwerer hat, gänzlich sich vom Gedächtnis zu befreien, je lebendiger letzteres ist, je schmerzlicher die aufgerufenen Vorgänge, je nachhaltiger ihre Wirkungen sind. Wo es um Konflikte der Erinnerungsorte geht, ist das naturgemäß der Fall.

Alles dies ändert nichts daran, dass man Gedächtniskonflikte in ihrer kognitiven Dimension nur entscheiden kann, indem man sie der Geschichte überlässt. Das verlangt von beiden Seiten die politische Entscheidung, alles zu unterbinden, was den Streit schüren könnte, und den Historikern freie Hand bei der Suche nach dem, was tatsächlich geschehen ist, zu lassen. Eingeschlossen ist hierbei die Bereitschaft, das auf diesem Weg erlangte Ergebnis auch zu akzeptieren. Für die Historiker ist das keineswegs eine leichte Aufgabe, auch auf ihnen lastet beiderseits das Gedächtnis. Und selbst wenn sie sich einigten und die Politiker geneigt wären, dies zu akzeptieren, beträfe das nur den Bereich, der sich mit Hilfe von Quellen klären lässt, mit anderen Worten nur das, was zum Objekt der Erkenntnis werden kann. Hierbei sind jedoch noch zwei weitere Dimensionen im Spiel, die emotionale und existentielle, die nicht in die Kompetenz der Historiker fallen. Wie versöhnt man nicht nur verschiedene Ansichten über einst Geschehenes, sondern damit verbundene Gefühle und Identitäten?

Verlangt ist hier nicht mehr ein historisches, sondern ein hermeneutisches Herangehen an den Ursprungskonflikt, das es ermöglicht, darin Züge des Tragischen freizulegen. Besser als Historiker scheinen Schriftsteller und Künstler dazu berufen. Sie sind in der Lage, vergangene Konflikte im Prisma individueller Schicksale darzustellen, ohne dabei Beschreibungen zu scheuen, die sich der Historiker mit Rücksicht auf sein Berufsethos versagen muss. Sie besitzen die Fähigkeit, sich in die Protagonisten sich einzufühlen, deren Motivation freizulegen, sie zu verstehen, ohne ihnen zuzustimmen. Auch vermögen sie die Erlebniswelt des Rezipienten anzusprechen, in ihm ein Gefühl der Gemeinschaft und zugleich völliger Fremdheit mit den dargestellten Figuren zu wecken, überhaupt Emotionen auszulösen, die zu einem Blickwechsel geneigter machen. Die Teilnehmer des Konflikts auf beiden Seiten erscheinen dann als tragische Figuren, von Göttern gelenkt, die sie selbst ins Leben riefen und welche entgegen den Erwartungen sie ins unvermeidliche Verderben stürzen: Geleitet von kollektiven Überzeugungen, religiösen Bekenntnissen oder Ideologien realisieren sie blindlings deren Losungen und schrecken dabei vor den grausamsten Verbrechen nicht zurück. Aber tragische Verblendung kann nicht als mildernder Umstand gelten.

Schließlich hat es auch andere gegeben, die den Ideologien oder Religionen nicht erlegen sind, oder auch solche, die sich ihnen zwar angeschlossen hatten, jedoch keine verbrecherische Konsequenz bei ihrer Umsetzung an den Tag legten. Jene, die bis zum Extrem gegangen sind, hatten gewiss eine – wenn auch eingeschränkte – Möglichkeit der Wahl. Also gelten für sie die Kategorien: Verantwortung, Schuld und Strafe.

Begreift man den Ursprungskonflikt als Tragödie, so entfällt die Möglichkeit seiner manichäischen Deutung als Kampf zwischen Gut und Böse. Es wird auf die Überzeugung verzichtet, wonach auf unserer Seite nur Opfer, auf der Gegenseite nur Täter zu finden seien. Daraus folgt freilich nicht, dass es beiderseits nur Opfer gegeben hätte, vielmehr, dass es hier wie dort Opfer und Täter gegeben hat. Opfer, die manchmal zu Tätern, und Täter sowie ihre Helfershelfer, die zu Opfern ihrer eigenen Verbrechen geworden sind. Wir haben es hier mit einer Abstufung zu tun; von der Vermischung von Gut und Böse bis zum Bösen in reiner Gestalt. Ein solches Verständnis des Ursprungskonflikts hat wesentliche Folgen für die Gefühle, die er hinterlässt. Hass und Rachegelüste erscheinen im Blickwinkel der Tragödie als Produkt jener Kräfte, die den Konflikt ausgelöst haben. Ihnen nachzugeben – und sei es nur in Gedanken und Worten – bedeutet, auf das Niveau der abstoßendsten Protagonisten sich herabzulassen. Dies mag nun das Bedürfnis nach Reinigung, nach einer reinigenden Erziehung der Gefühle wecken, welche das Mitleid mit den „Eigenen“ und den Hass auf die „Fremden“ ersetzt durch die Fähigkeit zu vergeben und das Mitgefühl mit allen, jene ausgenommen, die die Grenzen der Menschlichkeit verletzten. Hier endet allerdings die Kompetenz der Künstler und Schriftsteller. Von da an zählt die Stimme der weltlichen wie der geistlichen moralischen Autoritäten. Ein vorzügliches Beispiel für einen Akt der Vergebung ist der denkwürdige Brief der polnischen Bischöfe an die deutschen Amtsbrüder. Schade nur, dass ein ähnlicher Brief, soweit ich sehe, an die orthodoxen Bischöfe Russlands und der Ukraine nie verfasst wurde.

Erinnerungsorte sind, wie wir sehen konnten, aufs Engste mit kollektiver Identität verquickt. Dass manche von ihnen zugleich verschiedenen nationalen oder religiösen Gemeinschaften zugeordnet sind, ändert nichts daran. Es macht jedoch die ausschließliche Inbesitznahme eines gemeinsamen Erinnerungsortes durch einen der Miteigentümer ausnehmend gefährlich. Von den übrigen wird dies nämlich zwangsläufig als Enteignung eines Teils ihrer selbst wahrgenommen. Noch bedrohlicher erscheint seine Zerstörung oder verfälschende Umdeutung, worin untrüglich der Wille erspürt wird, die Spuren der Anwesenheit bzw. Tätigkeit eines anderen Kollektivs als das, zu dem der Erinnerungsort gegenwärtig gehört, auszulöschen. Eine symbolische Vernichtung. Und ein weiterer Beleg dafür, dass der Streit um Erinnerungsorte unweigerlich eine existentielle Dimension besitzt und somit dauerhaft nicht entschieden werden kann, solange allen darin involvierten kollektiven Identitäten nicht Genugtuung widerfährt. Praktisch heißt das, es ist die Pflicht des Staates, in dessen Grenzen sich Erinnerungsorte anderer Gemeinschaften befinden, ihnen nicht nur Schutz und Pflege angedeihen zu lassen, was wir, die Polen, gegenüber den in unserem Land befindlichen deutschen und jüdischen Erinnerungsorten lange vernachlässigt haben. Es gehört auch zu den Pflichten des Staates, den Interessierten Zugang zu den Orten zu gewähren und Rituale des Gedenkens ihrem jeweiligen Glauben oder ihrer Überzeugung gemäß zu ermöglichen. Dies ist eine notwendige Voraussetzung, um den Konflikt um einen Erinnerungsort durch die gemeinsame Suche nach Prinzipien künftigen Zusammenlebens zu ersetzen.

Solche Lösungen mögen den Konflikt entschärfen; ausschließen, dass er erneut entflammt, können sie nicht. Dazu braucht es beiderseits eines Umbaus der kollektiven Identität, der die Feindschaft gegenüber der anderen Seite als ein konstitutives Merkmal der Identität beseitigt. Hier müssen nun Erzieher im weitesten Wortsinn auf den Plan treten, nicht nur Lehrer aller Stufen, sondern Politiker, Geistliche, Journalisten und Medienmacher. Sie können und sollten die Arbeit der Historiker, der Schriftsteller und Künstler nutzen, wenn ihnen auch die korrekte Feststellung der Fakten oder das tragische Verständnis vergangener Konflikte nicht als das eigentliche Ziel gelten, sondern nur als ein Mittel. Diese Mittel erlauben es jedoch, die Erziehung der Gefühle durch eine in bestimmter Weise geprägte kollektive Identität zu stützen, so dass an die Stelle der Überzeugung von der eigenen Unschuld ein Bewusstsein der eigenen Verdienste und Vergehen tritt. Dann mag das Empfinden, immer im Recht zu sein, der Überzeugung weichen, dass die Wahrheit oft geteilt sei, und die Aussicht auf eine dauerhafte Koexistenz mag das Gefühl der Bedrohung durch Fremde ablösen. Eine solche neue Perspektive würde das Bild der eigenen Vergangenheit revidieren, so dass das manichäische Muster seine Herrschaft verlöre. Denn es ist durchaus nicht so, dass wir immer nur die Guten gewesen sind und böse stets die Anderen waren. Diese scheinbar banale Feststellung ist noch lange nicht von allen akzeptiert, die für die Erziehung in Polen Verantwortung tragen. Davon zeugen die Versuche, alle jene Fakten zu leugnen, die genau dieses belegen – muss man hier an den Streit um Jedwabne erinnern? In anderen Ländern übrigens verhält es sich nicht anders.

Neue Perspektiven

Historische Forschungen, das Schaffen der Schriftsteller und Künstler, die Arbeit der Erzieher, sie alle reichen nicht aus, um einen Zustand zu erlangen, in dem verschiedene Gedächtnisse mit dem Recht auf die je eigene Besonderheit koexistieren können. Dazu bedarf es vor allem des Verzichts der Politiker auf Entscheidungen, Auftritte und Aktionen, die die Bemühungen um einen solchen Zustand erschweren oder gar verhindern. Von ihnen sollte man wie von Ärzten erwarten können, dass sie wenigstens keinen Schaden anrichten. Das heißt, dass sie die Gedächtniskonflikte nicht parteipolitisch, im Kampf um die Macht instrumentalisieren, dass sie kein Misstrauen säen, keine Aggressionen schüren. Sie sollten der Frustration keine Nahrung geben und kein Empfinden allgemeiner Bedrohung verbreiten – die in der Innenpolitik von einem ominösen „Netz“ (System) ausgehen soll, das im Verborgenen sämtliche Fäden zieht, in der Außenpolitik wiederum von den ewigen Feinden, die uns wie die Wölfe dem Lamm auflauern. Das wäre das Minimum. Verlangen sollte man aber von den Politikern mehr. Nämlich positive Maßnahmen, die die Herausbildung offener Haltungen förderten, das fremde Gedächtnis respektierten, ohne auf das eigene zu verzichten. Es sollte die Überzeugung verbreitet werden, dass jede Nation aus sozialen Gruppen verschiedener Kategorien besteht, die die gemeinsame Geschichte unterschiedlich erleben und folglich verschiedene Erinnerungen daran bewahren. Ähnlich verhält es sich mit Europa, deren Nationen die gemeinsame Vergangenheit auf je verschiedene Weise erinnern. Die hierbei auftretenden Unterschiede haben ihre Berechtigung, freilich in Grenzen, die ein internationaler Diskurs aufzeigen und, wenn nötig, korrigieren sollte – unter Beteiligung von Historikern, Schriftstellern und Künstlern, Erziehern und Politikern. Alle Handlungen, die ein kollektives Gedächtnis konstituieren, die Vergangenes vergegenwärtigen und räumlich erfahrbar machen, sollten der Herausbildung solcher Haltungen dienen, also: Bildungsprogramme, Namensgebung öffentlicher Gebäude und Straßen, Errichtung von Denkmälern und Gedenkstätten, Jahres- und Gedenktage sowie die Pflege eigener wie fremder Erinnerungsorte.

Alles kollektive Gedächtnis ist geteiltes Gedächtnis, anders kann es offenkundig nicht sein. Nur heißt das nicht, dass die Teilung zwangsläufig einen Konflikt bedeuten muss. Wenn es in der Vergangenheit meistens so war, so deshalb, weil die Öffentlichkeit jedes Staates, jeder Nation von einer Gruppe beherrscht wurde, die der Allgemeinheit ihr Gedächtnis als das einzig verpflichtende oktroyierte und die Existenz anderer Gedächtnisse nicht zur Kenntnis nahm. Es bedurfte tiefer soziokultureller Veränderungen und eines langwierigen politischen Kampfes, der die soziale Hierarchie und das kollektive Gedächtnis gleichsam umgepflügt hat, bis die Gedächtnisse der verschiedenen Gruppen und Klassen Gleichberechtigung erlangten. Übrigens mehr in der Theorie als in der Praxis; in Polen zum Beispiel besitzt das adelskulturelle Gedächtnis noch immer ein größeres Gewicht als das bäuerliche. In der Vergangenheit nahm das geteilte Gedächtnis deshalb auch unausweichlich eine Konfliktgestalt an, weil die europäischen Staaten und Nationen keine andere Perspektive im Blick hatten als die Aufrechterhaltung – solange es irgend ging – eines Gleichgewichts der Kräfte. Es galt die erfahrungsgesättigte Überzeugung, dass jede Störung dieses Gleichgewichts unweigerlich zu einem am Horizont stets präsenten Krieg führen würde. Daher die Verschärfung der Nationalismen.

Zwischen den beiden Arten geteilten Gedächtnisses, dem innerstaatlichen und dem internationalen, sowie den daraus entstehenden Konflikten bestanden zeitlich veränderliche Wechselbeziehungen, die hier nicht zur Debatte stehen. Für uns ist nur wichtig, dass es gegenwärtig andere Perspektiven gibt. Innenpolitisch ist es die Perspektive der Demokratie mit dem Grundsatz der Gleichheit aller Bürger, außenpolitisch die europäische Perspektive mit dem Grundsatz der Gleichberechtigung aller Staaten und Nationen. Weder die Demokratie noch Europa sind etwas ein für alle Mal Gegebenes. Verschiedene Gefahren bedrohen sie, darunter das Schüren der innerpolitischen oder internationalen Gedächtniskonflikte durch populistische und nationalistische Parteien, die bei entsprechender Gelegenheit – einer wirtschaftlichen oder politischen Krise – an die Macht gelangen und ihre Ideologie in staatliches Handeln umsetzen können. Aus der doppelten Perspektive also, der Demokratie und Europas, ist es besonders wichtig, Gedächtniskonflikte zu entschärfen, wie man Bomben mit Spätzündern entschärft.

Am Anfang stand die Überlegung, dass alles Gedächtnis eines individuellen oder kollektiven Subjekts bedarf. Das kollektive Subjekt ist dabei kein Abstraktum oder eine Hypostase. Es ist der Zusammenschluss Einzelner durch vielerlei Bindungen; durch gemeinsame Arbeit, gemeinsames Handeln, gemeinsame Empfindungen. Somit betrifft die Einstellung zum kollektiven Gedächtnis, dem eigenen wie dem fremden, in letzter Instanz stets die lebendigen Menschen. Sie sind seine Träger, sie aktualisieren und vergegenwärtigen Vergangenes in der Regel mit Hilfe von Objekten und Orten, die, weil sie als Korrelate des Gedächtnisses gelten, den Menschen besonders nahe sind und als Teil ihrer selbst betrachtet werden. Die Einstellung einem fremden kollektiven Gedächtnis gegenüber kann nicht nur eine politisch durchgesetzte Rechtsvorschrift regeln, wiewohl diese wichtig ist. Sie muss vielmehr auch, wenn nicht gar vor allem, den vom Individuum verinnerlichten moralischen Normen entspringen, die vom Grundsatz der Gegenseitigkeit abgeleitet sind. Dieser gebietet in der Person des Anderen ein zweites Selbst zu erblicken, in der anderen Gemeinschaft wiederum das Äquivalent der eigenen, zu der wir gehören – und sich entsprechend zu verhalten.

Jüngst wurde bei uns viel über „Geschichtspolitik“ gesprochen. Ich schlage vor, sie durch Ethik des Gedächtnisses zu ersetzen.

Aus dem Polnischen von Heinrich Olschowsky

Prof. Krzysztof Pomian (geb. 1934) - Historiker, Philosoph, Essayist. Professor im französischen Nationalen Zentrum für Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen. Direktor des in Brüssel entstehenden Europa-Museums.